![]() Pure Earth and UNICEF reported in 2020 that, globally, one out of three children are exposed to dangerous levels of lead, a poison that gets into the bloodstream, then impairs the brain and the body in many ways.

Pure Earth and UNICEF reported in 2020 that, globally, one out of three children are exposed to dangerous levels of lead, a poison that gets into the bloodstream, then impairs the brain and the body in many ways.

The United States has made great progress toward reducing lead exposure from gasoline and paint. But more work is needed to protect all American children, including those whose exposure to lead during early childhood — and even while in their mother’s womb — has been linked to behaviors landing them in the juvenile justice system.

The magnitude of lead’s impact on brain development and anti-social behaviors should make us rethink the role of retribution in criminal justice, considering how lead exposure has hit poor children and Black children disproportionately. If some racial disparities in felony arrest and incarceration rates could be explained by earlier disparities in lead exposure, then should we oppose early release of prisoners who have modeled best behaviors while incarcerated just to punish them for crimes caused by lead poisoning?

Children often ingest lead in microscopic house dust as they crawl and put their hands in their mouths. The Environmental Protection Agency warns that 10 micrograms of lead per square foot is hazardous. A single grain of salt is about 60 micrograms.

Leaded gas emissions settled as lead in dust, and emissions surged with gasoline use after 1945. In the United States, leaded gasoline use peaked around 1970 and fell to near zero in 1987. But lead in residential water pipes and dust from lead paint in older homes still affects many children today.

No levels of lead in the blood are safe

In 2012, the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention stated that there is no safe blood lead level for infants through 5-year-olds, even as it lowered its level of concern from 10 to 5 micrograms of lead per deciliter of blood (mcg/dl).

More than a dozen peer-reviewed studies have shown a clear association between lead exposure and crime. Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center tracked 250 19- through 24-year-olds born between 1979 and 1984 and found that preschool blood lead over 5 mcg/dl was associated with a higher risk of a young person with that level of lead poisoning being arrested for violent and property crime. And arrest rates rose with each 5 mcg/dl increase in blood lead. The offending risk is small for any individual child with blood lead just over 5 mcg/dl, but that small risk increases arrests across a large population, with greater risks at higher blood lead levels.

Declines in bloodstream lead and juvenile arrests

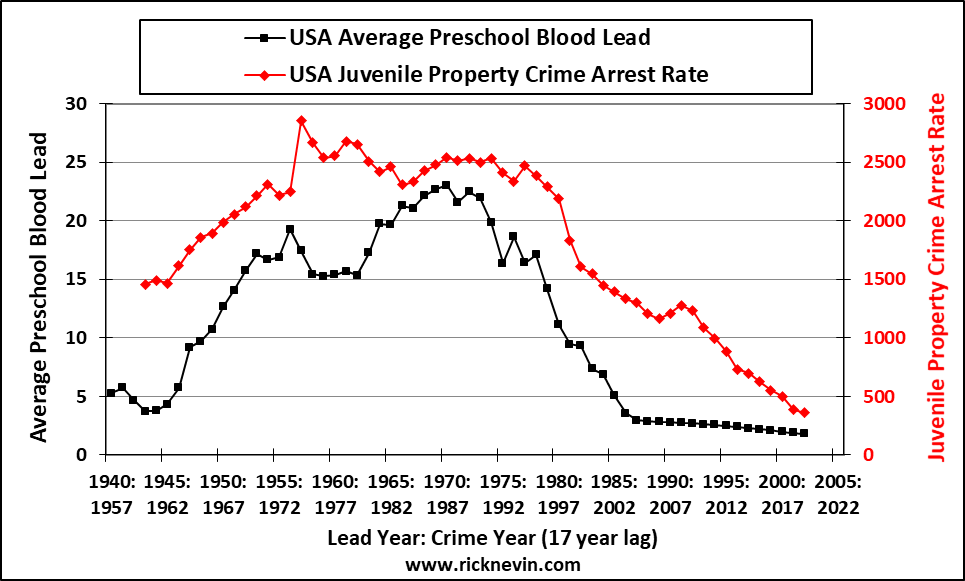

For six decades, the juvenile property crime rate has mirrored trends in preschool blood lead levels, with those crimes reflecting lead exposure levels roughly 17 years earlier. That lag reflects the delayed impact of lead exposure during critical early brain development. Brain scans at ages 19 through 26 showed preschool lead exposure affects the same types of brain function linked to “diminished culpability” in the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2005 decision outlawing the death penalty for those convicted of murder before they were 18 years old.

Juvenile arrests from 1960 through 2000 reflected the rise and fall of lead emissions from the 1940s through the 1980s. There were extreme racial disparities in lead exposure in the 1960s and 1970s because Black children disproportionately lived in slum housing with deteriorated lead paint and in cities with higher air lead due to vehicular traffic.

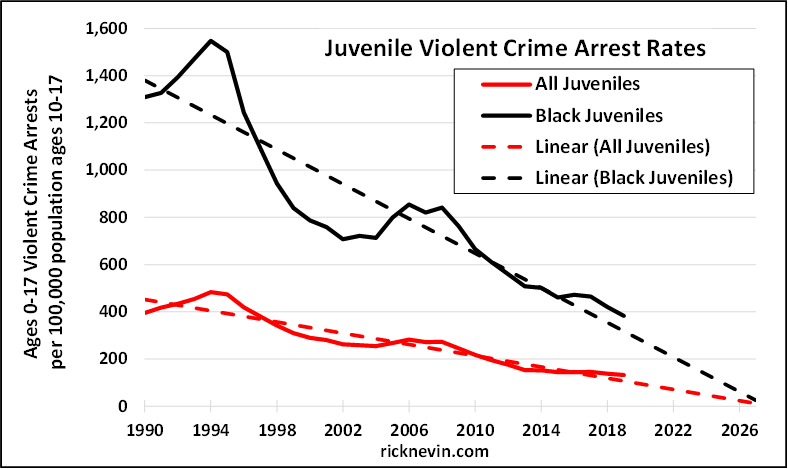

The leaded gasoline phase-out sharply reduced racial disparities in severe lead poisoning. From the late-1970s to the late-1980s, the proportion of white children with the highest levels of lead in their blood fell from 2% to less than 0.5%; the respective decline for Black children was from 12% to less than 1%. That steep decline for Black children foreshadowed an astonishing 81% decline in Black juvenile homicide arrest rates from 1993 through 2004.

Criminologists agree that many factors affect crime, citing correlates that include race, poverty and single-parent households. But those usual suspect correlates offer no insight into the massive decline in homicide arrests of Black juveniles from 1993 through 2004. There was no significant change in child poverty or single-parent households among Blacks over those years.

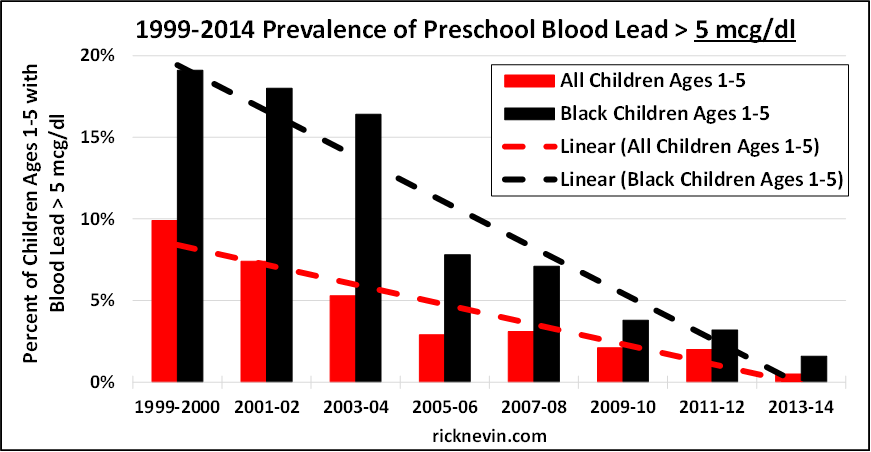

The Lead-Based Paint Hazard Reduction Act of 1992 has further reduced elevated blood lead and racial disparities in those levels.

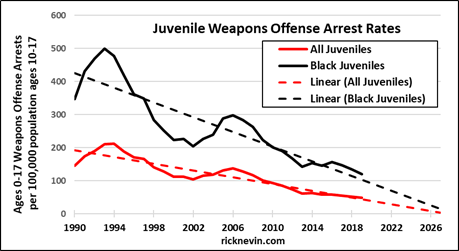

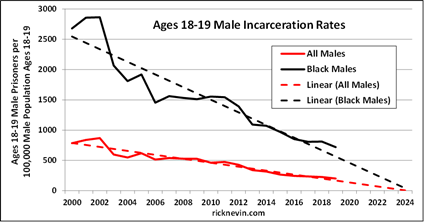

Overall declines in elevated blood lead since the 1970s, with even steeper declines for Black children, presaged juvenile arrest declines for violent crime, felony property crime, and weapons offenses from 1990 through 2019. These are serious felonies, not misdemeanors affected by selective policing in some jurisdictions. Moreover, the same decline and racial convergence pattern was evident in 2005 through 2019 National Crime Victimization Survey data on gangs in schools, and in 2000 through 2019 prisoner data showing a 74% decline in the incarceration rate for men ages 18 and 19.

If trends reflected by that data continue, one might project that juvenile arrest rates and gangs in school could fall to near zero in the mid-2020s. Of course, that’s a risky forecast. But we do have research showing higher arrest rates among those with blood lead over 5 mcg/dl, and declines in the percent of children above that level through 2014. Juveniles who were 17 in 2019 were born in 2002, when 7.4% of children had blood lead above 5 mcg/dl. So, at the very least, we should expect ongoing juvenile arrest declines associated with birth years through 2014, when prevalence above 5 mcg/dl was 0.5%.

Most criminal behavior begins during teen years

Only 10% to 30% of those convicted of crimes start offending after adolescence, so 90% to 70% of adult offenders are former juvenile offenders. This means declining juvenile crime will cascade through older age groups as the worst years of lead exposure recede into the past. Again and again, federal data show that the pattern already is evident in arrest and incarceration trends over recent decades, when there were massive declines for young adults but arrest and incarceration rates are still rising for older adults born near the 1970 peak in lead emissions.

For more information on juvenile justice issues and reform trends, go to

► JJIE Resource Hub

In October 2020, Pure Earth, the Clarios Foundation and UNICEF launched the global Protecting Every Child's Potential initiative to prevent preschool blood lead above 5 mcg/dl. Could achieving this goal reduce crime to near zero … worldwide?

In the United States, prisoners over age 60, born into the worst years of lead poisoning, are the fastest growing segment of the prison population. Recidivism for prisoners released after age 60 is much lower than for prisoners released at a younger age. Retribution is not a morally defensible reason for keeping those elderly Americans in prison until they die.

Economist Rick Nevin’s research on preschool lead exposure and crime has appeared in, among other publications and peer-reviewed journals, Energy Policy, Environmental Research, Physiology and Behavior and The Appraisal Journal. His research has been cited in The Washington Post, Mother Jones and USA Today.