Videographer: Jacob Langston

Adrift after his father was shot and killed during an argument with a man at a Jacksonville, Fla. bar, then 14-year-old Robert LeCount spent several years burnishing his reputation as a drug-dealer and star athlete.

“We had football rivalry, we had basketball rivalry, we had baseball rivalry. That's how we dealt with a lot of things. Our energy was in the sports and in different activities.” said LeCount, now 63, a Disciples of Christ pastor whose son, then 22, was shot in their Florida hometown in 2003.

The parks hosting young athletes like the elder LeCount were well-maintained and -staffed back then. They had bats, gloves, balls and other equipment that many parents in the mostly Black neighborhood couldn’t afford to buy for their children.

“Right now,” he began, noting how much things have changed, “if you go in our community, we have parks that you have access to. But you don't have no park managers to manage that park, that would have cared for that park, that would have cared for your children.”

That lack, symbolically, reflects a proverbial tale of two cities, said Fourth Judicial Circuit State Attorney Melissa Nelson of Jacksonville. Nelson, other expert observers and some residents contend that the duality also is reflected in the local murder rate in an area where 80% of murders were by firearms in 2020 and Black men killed by gunshot dominated the body count.

At least in part, residents also argue, that rate reflects a failure to invest in employment, anti-poverty and child development programs and even park maintenance that many residents on LeCount’s side of town believe is critical to cutting crime. But elected officials, instead, have poured what those critics argue is a disproportionate amount of tax dollars into policing and propping up the well-to-do.

Researchers at the Brookings Institute are among the latest to link poverty and crime. In their November 2021 report, “Want to reduce violence? Invest in place,” they wrote: “ … [O]ne must pay attention to the long-standing relationship between violence and place. Within cities, gun violence is concentrated in a small set of disinvested neighborhoods, and within these neighborhoods, such violence is even more concentrated within a small set of ‘micro-geographic places,’ like particular streets. This is a well-established trend that holds in every city or non-urban setting in which it has been studied.”

In Jacksonville, critics of how city officials have opted to spend taxpayer dollars cite, for example, the $114 million in tax refunds, infrastructure improvements and $26 million in cash that the city council in October approved for NFL Jaguars’ owner Shad Khan’s riverfront hotel development.

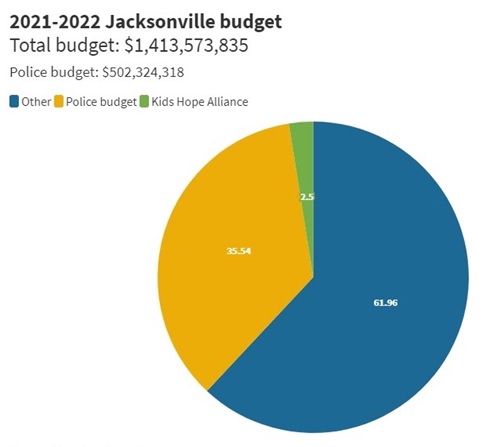

More than a third of Jacksonville’s $1.4 billion fiscal 2021 budget went to the Jacksonville Sheriff’s Office, which doubles as the city’s police force and runs the county jail. (Throughout much of the nation, sheriff agencies, which oversee jails, are separate from police.)

City officials believe the “fallacy,” said activist Ben Frazier, that they can “arrest themselves out of the problem” when inequality is a major driver of many crimes.

“We are suggesting that, until the city actually looks at economics as an intrinsic part of this problem, all those other things are simply Band-aids being applied to an open and festering wound,” said Frazier, whose nonprofit organization, the Northside Coalition of Jacksonville, advocates for social, racial and economic equity.

Black poverty rate is double and Latinx rate is two-thirds higher than whites'

In an area where, compared to whites, Blacks have double and Latinos two-thirds the rate of poverty, city officials have directed resources toward what they view as long-range crime prevention efforts. They've appropriated $35 million to children’s programming annually in recent years. In 2017, they launched a $1.5 million pilot program to treat opioid addiction. LeCount’s nonprofit, Quench the Violence, recently received a $225,000 community development grant.

That’s minimal, said Frazier of the Northside Coalition, considering the hundreds of millions of dollars funneled yearly to the city’s moneyed establishment.

Blight on Jacksonville's Northside and elsewhere has been longstanding. It existed in 1968, when Duvall County's sheriff department and Jacksonville's police departments were combined. Proponents of that consolidation had considered it a fresh start after a decade in which city officials were indicted for corruption, the high school system lost accreditation and cash-strapped city and county governments struggled to meet the growing metropolis’ needs for roads, drainage, other infrastructure, trash pick-up and zoning code enforcement.

“Unfortunately," Frazier said, "the city never fulfilled its promise to provide adequate city services to everyone, which was what the pitch was back then.”

Residents in the urban core were told that growing tax revenue would finance improvements to neighborhoods, schools and quality-of-life. Instead, more than 50 years later, septic tanks that back up during heavy rains still haven't been removed from some urban neighborhoods. During the push for consolidation, residents of those neighborhoods were told they would be hooked up to municipal water and sewer lines, Frazier said, noting a major unfulfilled promise.

Since the 1970s, Jacksonville’s murder rate has surpassed the state’s and nation’s

In the 1970s, Jacksonville’s murder rate more closely mirrored that of the state and nation; and 1980 marked the only time, during the last 50 years, the city's murder rate was lower than the state's. As murders and gun violence climbed nationally throughout the 1980s, Jacksonville experienced similar increases, with its murder rate cresting at nearly 26 per 100,000 in 1990, Florida Department of Law Enforcement records show.

Jacksonville's murder rate fell to a low of 10 per 100,000 in 1999, state records show, before climbing again to its current rate of 15 per 100,000. State and national murder rates steadily fell throughout the 1990s before dropping to between five and six per 100,000, and hovering there for the last two decades.

Almost every year for the last two and a half decades, Jacksonville has been the murder capital of Florida.

The city has responded by pumping more money into policing. In the 1980s, the sheriff's office’s portion of the budget doubled from 15% to 30%, city records show. This year that office will receive more than a third of the city’s $1.4 billion budget.

Commissioned by the Jessie Ball DuPont Fund, the "JustJax, 2021" report noted that the city has long emphasized policing as a solution to violent crime in lieu of other approaches: “Historically the responsibility for this community safety has been almost entirely laid at the altar of law enforcement. But the reality is that the effect of simply responding to crime after it occurs is limited, and most importantly, is insufficient. As we heard repeatedly throughout this project, law enforcement alone has not and will not stop the violence in Jacksonville. By the time the police arrive it is too late. Jacksonville must also focus on preventive measures before it is too late.”

LeCount, the preacher, is clear that a small number of individuals are responsible for a disproportionate amount of violent crime and murders. He believes policing is essential, especially in the communities most beset by crime. However, he added, police seem less and less woven into the fabric of the communities they are sworn to protect and serve.

“I knew the police.” LeCount said, noting the rapport he believed existed between police and residents when he was a boy, “ … because they come out, they hang out, walk through the neighborhood.”

Having strong relationships with residents may help police better identify and respond to problems, he said

LeCount, whose Northwest Jacksonville neighborhood has the city’s highest murder rate, continued: “We shot dice a lot in our community … [Police would] come in and break up the dice game and say, ‘Come on back and y'all get your money back.’”

No one was arrested for that illegal activity, a misdemeanor, he said.

Experts: Combatting crime comprehensively means zeroing in on socio-economic factors

Former local prosecutor John Delaney, who also was Jacksonville’s mayor from 1995 through 2003, said his work made clear to him the interconnections of poverty, race, racism and crime.

“ ... [P]oor, unemployed, hopeless people often turn to stealing to eat and drugs to escape,” he said. “And violence begets.”

Delaney said that in the 1980s, when he was prosecuting cases, the city didn’t have a comprehensive approach aimed at preventing murders and other crimes. As murders skyrocketed, its answer was to pump more money into the sheriff's office.

Some, including then-State Attorney Ed Austin, held a different view, Delaney wrote via email. When Austin became mayor in 1991, he launched what would become the Children’s Commission with $2 million. In a letter prefacing the 1991-92 budget, Austin, who died in 2011, wrote, “We will build a structure that affords our children better protection from ignorance, from neglect, from becoming victims or perpetrators of crime.”

His goal, Delaney said, was to eventually allocate 2% of the city’s annual budget towards children’s programming and resources. For the next decade, Jacksonville increased the commission’s funding. In 1999, it received $11 million, records show. This year, $35 million was allocated to children’s programming through what’s now called the Kids Hope Alliance, an umbrella program that includes the commission.

There were other signs of shifting thought about how to prevent crime. In 1991, the State Attorney’s Office began offering youth diversion programs, to keep certain juvenile offenders in community-based programs instead of detention facilities.

That same decade, under then-Sheriff Nat Glover, now the president of Florida’s oldest historically Black college, the sheriff's office embraced community policing. In 1996, the Florida Times-Union reported that residents and police agreed that a decrease in crime, including murder, was due largely to his reforms. Murders had reached a 10-year low in 1999.

“We're seeing some changes because, now, some police officers see the importance of community policing,” resident Marcy McCann told the newspaper. “The new sheriff and new attitude of police are the reasons crime is declining.”

In 2003, when Glover left, the city essentially abandoned community policing. The murder rate rose again. Beverly McClain’s son was a part of that count. Andre Johnson, then 28, was found floating in the Ribault River.

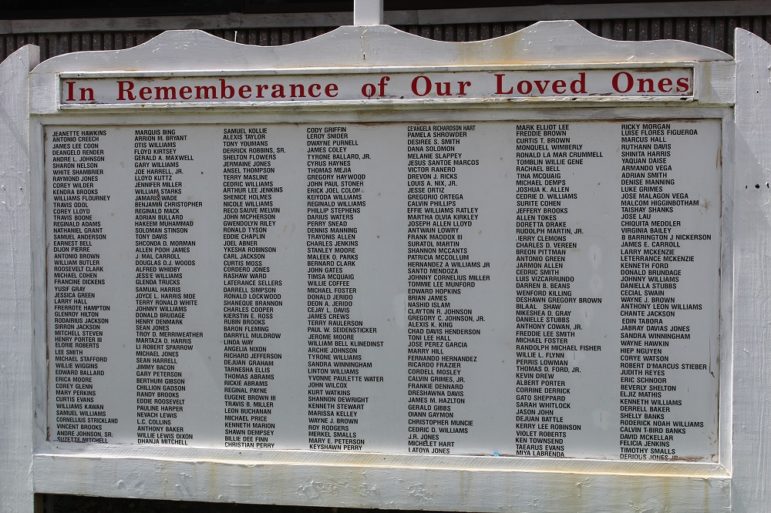

“I don’t even know who did it,” said McClain, founder of Families of Slain Children, a nonprofit offering support and resources to people who’ve lost loved ones to violence. Signs in front of the building, located in the same violence-prone neighborhood as LeCount’s church, bear the names of hundreds of victims. Most died by gunshot.

Claire Goforth

Names of those killed, mainly by guns, on a sign outside of Families of Slain Children in Jacksonville, Fla.

As murders skyrocketed, in 2007, then-Mayor John Peyton sought solutions focused on rehabilitation, programs to ease the transition of formerly incarcerated persons to their home communities, crime prevention and intervention. Jacksonville Journey, which provided kids’ programming and resources, was a lauded product of that.

“The Jacksonville Journey will need a dedicated revenue stream, money that can't be raided by future city councils or mayors,” Florida Times-Union columnist Ron Littlepage warned, at the time.

Journey’s initial funding of roughly $15.5 million came from a $31-million pot, derived through cuts elsewhere in the budget, with the rest of those monies going to the sheriff's office and for capital improvements.

Since then, Journey’s budget perennially shrank. In 2013, it received $8 million. The following year, its budget was roughly $2 million.

As Journey’s funding dried up, the local prosecutor’s office was being criticized for what some deemed as it tough-on-crime approach. In 2014, the Florida Times-Union editorial board blasted that office for sending non-violent and juvenile offenders to prison at higher rates than other Florida cities, calling it “dumb justice,” a punitive approach that didn’t stop the murder rate from climbing.

Except for small declines in 2013 and 2015, the annual murder rate has risen every year since 2011.

Jacksonville, again, eyes crime prevention and reform, rather than harsh punishments

In recent years, Jacksonville has again re-focused on prevention and reform. In 2018, Mayor Lenny Curry resurrected children’s programming that, in part, is designed to lower crime over the long-term. In 2019, the city launched Cure Violence, an Annie E. Casey Foundation-funded project whose public health lens views violence as a contagion. Earlier this year, Cure Violence leaders added a third crime hotspot to what initially were two.

State Attorney Nelson, who took office in 2017, also has endeavored to target violent offenders, while giving low-level drug offenders, including juveniles, opportunities to avoid incarceration.

“We've tried to use our platform to lend support to preventative efforts. We've partnered with nonprofits. We've put prosecutors on boards of nonprofits,” Nelson said.

Residents themselves have ramped up their efforts to stop the bloodshed, launching nonprofits and other groups, including Frazier's Northside Coalition, McClain's Families of Slain Children and LeCount's Quench the Violence. Collectively, they aim to reduce shootings and violent crime through awareness and community development.

“It takes all of us,” people, politicians, police, pastors, pretty much everyone, LeCount said. “ ... to try to fix this problem that we have in our city.”