![]() One by one, we got up to tell the judge what we'd been up to during our participation in a drug court program designed to keep us out of prison. I’d been accepted into that diversion project after being charged in 2004 with felony cocaine possession.

One by one, we got up to tell the judge what we'd been up to during our participation in a drug court program designed to keep us out of prison. I’d been accepted into that diversion project after being charged in 2004 with felony cocaine possession.

When it was my turn at the podium, the judge unveiled a confidential informant’s photos of me selling weed a few weeks prior. Aware that other sellers likely were among the rest of the program’s enrollees, the judge made an example out of me. He made a production of it, standing with his arms aloft as though he were summoning lightning to strike from the heavens. He thundered something about bringing the roof down on our heads if we blew the second chances we’d been given.

When he was done shouting, three bailiffs cuffed my wrists, ushered me out a side door and into a holding cell. Thus began an 11-month hiatus from my freedom. I was 21.

Since I was 18, I’d been selling marijuana in and around my suburban town of Nyack, N.Y., a 45-minute ride from Manhattan. My reputation was built on making myself available 24/7 to deliver my product and offering high-grade strains of it from my contacts in Washington Heights, a heavily Latinx uptown Manhattan neighborhood where a white dude like me stood out.

From the courthouse, I was remanded, without bail, to Rockland County Jail. The next morning, I lifted myself off a three-inch-thick mattress, stood and stared out of a window high on the wall of my cell. Blue sky is all I could see. A resolve swept over me: “You need to get through whatever lies ahead so you can get out in the world and discover what life is really about. There has to be a better way to live.”

I made that pact with myself.

I’d been arrested five times since I was 16: burglary, weapons possession and drug charges.

Twice, someone had threaten to put a bullet in my brain. The last time it happened was six months before that day in court with the thundering judge; my Washington Heights connection had set me up to be robbed of weed I'd just picked up from him to sell to my customers. That gun to my head was one in a spiral of events that led me to buy a Smith & Wesson .380 pistol from a friend. My drug-dealer decisions were placing me in increasingly life-threatening situations.

Awaiting my last prison sentence in a jail cell block with brawlers

For the four months spent in jail awaiting my prison sentence, mine was one of 15 cots in one of four rooms in a dorm-style cell block. It had two stainless steel tables with four steel stools affixed to each and a TV that seemed stuck on “The Jerry Springer Show.”

The background in the photos the judge held up helped me figure out which of my weed customers was the informant. He occupied one of the 15 cots. I made this known to the rest of the dorm. They urged us to fight it out in the adjacent bathroom, an area not captured by monitors wired to a central control room where the guards kept their sights on every dorm in the wing.

I laced my shoes combat-tight and waited for the guard to be distracted, thinking I’d rush into the bathroom and take the informant off his feet before he landed too many hits. Coming to myself, I hesitated. Actually, I had a distaste for violence. Plus, my court-appointed public defender had warned that any further trouble on my part might prompt the judge to sentence me to more than the six years he was considering. That reality overrode my ego. I blamed the guard for not being distracted enough for me to proceed. Our dorm mates harassed the informant until he requested to be moved.

The jail didn’t bother to keep potential combatants separated, or to even check for conflicts that could erupt within forced, close proximity.

I cringe whenever I remember how the uncle of a 20-something homicide victim was taunted by the murderer who’d lured that young man to a drug deal and shot him to death. I overheard the killer bragging to other inmates about his antagonism toward the uncle when they’d been housed in the same wing.

Once, out of my earshot, a middle-aged man in my 15-person dorm accused me of eating slowly to avoid the clean-up we were required to do after dinner. Kareem, a guy my age who I knew from Nyack, argued on my behalf, sticking with it even as things escalated and he and the older guy challenged each other to “take it to the bathroom.”

Reemo, as we called Kareem, laced up in my defense, though the situation died down without a fight. Reemo and my accuser were Black. I couldn’t see what Reemo stood to gain by putting himself out there for a skinny white kid — in a place where tribalisms dictate that you’re safer when sticking with your own kind. His readiness to sacrifice for me didn’t compute. It felt good, though.

Laboring in a prison boot camp

The judge sentenced me to two years in state prison and, after my release, three years under a parole officer’s supervision. After the sentencing, during an interim stop at a sprawling maximum-security facility where prisoners, mainly from the New York City area, are processed and funneled to prisons often hundreds of miles from home, I watched three guards get rough with another recent arrival. While his hands were cuffed behind his back, they slammed him into a wall, then down onto a table, then into a locked room near the holding pen where I waited my turn to be processed. His face appeared in the door’s tiny window, rage in his eyes.

From there, after several weeks of being shuttled through different facilities across the state, I wound up in the Catskill Mountains at a minimum-security prison boot camp run with military-style discipline. Six months later, 35 in our group of 50 were paroled for successfully completing what’s called shock incarceration. We hauled felled trees out of the forest or sawed them into firewood for the camp’s ovens. Everything was regimented. Eight minutes to eat, eight minutes to shower.

Yet, I was lucky to be in that camp. In a more normal prison, assault and rape are constant, potential perils.

The whole prison experience, including the boot camp, was jarring and dehumanizing. It erased any illusions I had about the system’s willingness or capacity to rehabilitate human beings.

The fits and starts of traveling a new path

Within a year of my release from boot camp, I was cited with my first parole violation. I'd been out after curfew and consorting with a known criminal, which is disallowed for parolees. A local cop recognized me while I'd chatted with Reemo outside a bar. Both of us were taken into custody at our next official check-in with parole. The rest of the parolees present were instructed to stand with their faces to the wall while we were cuffed, our misfortune on display. It felt familiar.

After another short stint in jail, I had what felt like a flash of criminal brilliance: They’d never be able to catch me for anything if I didn’t do anything they could catch me for.

It was the first time I consciously prioritized my welfare over my impulses. It felt new. Gradually, I changed how I thought and behaved. I surrendered my earnings as a dealer, the identities I’d constructed to keep that cash flowing and whatever social status that gave me in the universe I'd been orbiting.

This was an adjustment.

I returned to Westchester Community College, earning straight As in my final semester. When I applied to State University of New York campuses in Binghamton and in Albany, special panels reviewed my criminal history and denied me admission. They encouraged me to apply again the next year. But I received an acceptance letter, no questions asked, from my third choice, the State University of New York at Stony Brook on Long Island.

When an associate dean of its newly re-launched school of journalism pitched its program, something clicked. While in jail, I’d been transfixed by Time correspondent Michael Weisskopf’s essay about having his hand blown off in Iraq and adjusting to a metal hook that replaced his flesh and bone. I believed I also could tell those kinds of resonating, real-life stories.

I signed up for a journalism course. After one of my pieces was published on the school website’s homepage, I signed up for more. I painted penthouse apartments in Manhattan over the summers and during breaks to pay for what my student aid didn’t cover. My parents, relieved and cautiously thrilled that I’d found a direction, buoyed me.

I kept studying and writing and changing. At a campus party, when a drunk, aggressive, muscle-bound guy’s easy target was a smaller kid, I stood between them. The diminutive guy’s hand quivered as he gripped a red Solo cup and his eyes darted around the room. I got the bully’s attention and made small talk while I led him out of the suite. On another night, a friend and I gently shook awake an unconscious-looking young woman in a dormitory’s common area. She was too intoxicated to stand on her own feet. We helped her call a friend and waited for him. When he arrived, he looked us in our eyes. “Thank you,” he said.

Reemo’s lacing up on my behalf that night in that jail was an intervention I didn’t request. He stood by me simply because he saw an unjust threat. He asked nothing of me in return. So, I was following Reemo’s example. This was like playing with a new toy. It was a new game, a new paradigm. Put positivity out, get positivity back.

The formerly incarcerated as change-makers

I find that formerly incarcerated people who’ve found a path out of self-destruction often are more willing than many others to give of themselves. Once, over lunch, I told Lawrence Bartley, a formerly incarcerated man who is a journalist at criminal justice-focused The Marshall Project, that I wondered if the pressures of our industry, or life in general, could erode my mental health to the point that I’d push the “F it” button again.

“That’s when you call me,” he said.

Trading in my me-against-the-world mindset has led me to a new tribe, a support system for the long-haul work of staying out of trouble and living by a new set of principles: Do not harm. Do not violate trust. Stay on your path.

In a poll conducted by The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research, 95% of Americans said they supported some level of criminal justice reform. As our society recognizes the flaws within the justice system, we must provide more room for the growth of people who’ve been harmed by it — despite the harms done by law-breakers. Toward that effort, Floridians passed a measure to restore voting rights to people convicted of a felony. New York City lawmakers ordered that employers can no longer ask about criminal histories or do background checks before making a conditional offer of employment to an applicant.

Three percent of the American population has spent time in jail or prison. More than 600,000 people are released from state and federal prisons each year and millions more filter through local jails. A disproportionate number of them have, almost from birth, faced the kinds of adversities that some researchers argue heighten their risks for landing behind bars.

As experts with lived experience in the myriad ways our justice system falls short, those individuals should be invited to every conversation on reform. Those who have healed sufficiently should be sought for their insights on how to best address criminality. Their involvement can help protect society from the cynical, hopeless acts of young people who, today, are as lost as I and many of my incarcerated peers were.

We should look to them for more than feel-good stories about the formerly incarcerated getting a second chance. People who have redeemed themselves are uniquely suited to guide others toward redemption. Some — but not enough — of them are leaders, including at some of the nation’s largest criminal justice-focused organizations. Others are leaders-in-waiting.

We need to make more space for them. That is my wish and my hope.

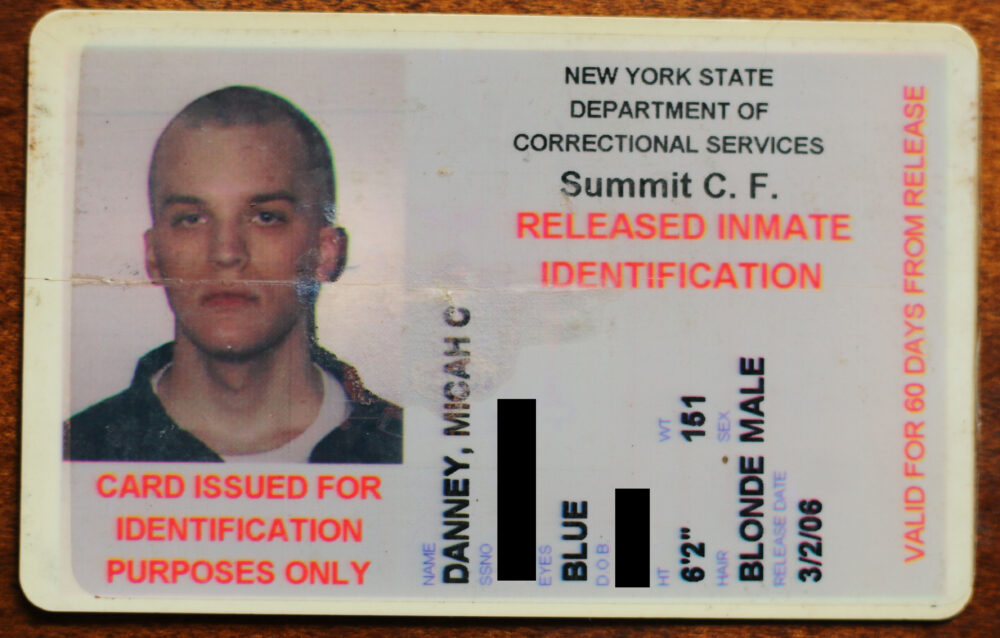

Criminal justice journalist Micah Danney reports regularly for JJIE. He lives in New York.