Almost all of 112 Philadelphians who have been released from lifetime prison sentences said they participated in some form of prison programming, but 53 percent reported having been restricted from vocational programs such as barbering (Pennsylvania prioritizes people who have less than five years left on their sentences for vocational training). Sixteen percent of those former juvenile lifers mentioned college credit courses when asked what programs they were shut out from.

Those were among the findings in a recently published policy brief on the reentry experiences of juvenile lifers in Philadelphia, which has the highest number of juvenile lifers in the country, according to researchers at Montclair State University in New Jersey, who authored the brief. Researchers also concluded that 82 percent of those surveyed participated in GED classes and 40 percent had some college programming.

“A lot of these guys who did end up taking advantage of the college programming were able to enroll through their perseverance as opposed to these programs being allocated for them,” said study co-author Tarika Daftary-Kapur, professor of justice studies at Montclair State University in New Jersey, which conducted the survey.

Roughly 80 percent of those surveyed Philadelphians who, as juveniles, were sentenced to life in prison had been suspended from school at least once and about half had been expelled before they were incarcerated. Sixty-four percent reported earning poor grades in school, researchers found.

Additionally, researchers wrote, 63 percent were raised in a household headed by one parent; 69 percent were physically disciplined at home; and 63 percent had experienced poverty.

Together, Pennsylvania, Michigan and Louisiana account for two-thirds of all juvenile lifers in the United States, researchers wrote in an earlier analysis. Pennsylvania has been ahead of the other two states in its resentencing efforts. That research team’s previous analysis concluded that less than 1 percent of those who were released on parole early committed a crime that landed them back behind bars.

Montclair State University

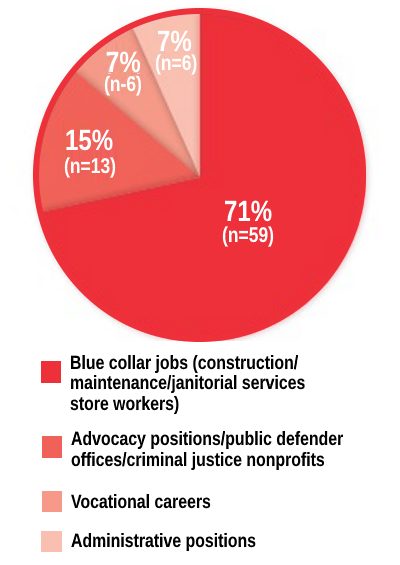

Re-entry vocations.

As more and more juvenile lifers, who were sentenced when they were under 18 years old, are being released through sentencing reforms following the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2012 Miller v. Alabama ruling and its 2016 Montgomery v. Louisiana decision, the researchers sought to document their experiences before, during and after incarceration.

The survey respondents were between the ages of 38 and 67 at the time of the survey and had been incarcerated between 21 and 49 years. The majority of the juvenile lifers were male (94 percent) and Black (82 percent).

Although programming in general did not have a significant impact on juvenile lifers’ reentry experiences, participating in college classes may have had an effect on the type of jobs they had post-release, researchers concluded.

Seventy-one percent had jobs in areas such as construction, maintenance, janitorial services or retail. Around 22 percent were working in advocacy or the legal or nonprofit sectors or held administrative positions.

Daftary-Kapur said that while the numbers are too small to show a statistical significance between college classes and type of employment, follow-up interviews indicate that those who had college classes might be more likely to find white-collar jobs. “Those who sought out college credits seem to be the ones who landed those types of positions, based on early analysis,” Daftary-Kapur said.

Montclair State University

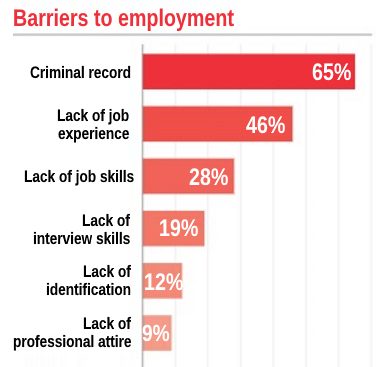

Employment barriers.

Twenty-nine percent of the surveyed juvenile lifers reported that finding employment was their biggest challenge for reentry. Along that continuum, 65 percent said having a criminal record was the biggest barrier to employment; 46 percent said lack of job experience was the biggest factor and 28 percent noted that a lack of job skills was the biggest obstacle.

Only 20 percent of respondents said that accessing educational opportunities was “the most challenging aspect of reentry.” Daftary-Kapur said that their follow up interviews show that most juvenile lifers were not looking for educational opportunities after release. “It seems like education isn't the top priority when they're coming out,” she said. “It's really getting a job, finding housing, and reconnecting with family.”

One of the recommendations made by the researchers was to provide more programming and training for juvenile lifers, especially as a growing number of states are passing “second chance” laws. “As such, it might be prudent to revise policies that restrict lifers and virtual lifers from educational and vocational programming,” they wrote.

A version of this article was produced by Open Campus, a publishing partner of the Juvenile Justice Information Exchange. Open Campus national reporter Charlotte West covers postsecondary prison education and writes Open Campus’ biweekly College Inside newsletter.