In a letter to the Durham County Commission in North Carolina, prison journalist Lyle C. May, who is incarcerated in Raleigh, N.C., opposed its unanimous vote to spend $30 million on a new juvenile jail. Its 10 signers, including May, were under 18 years old when they went into the juvenile justice system.

This is an abridged version of the letter penned by May, whose “Witness: An Insider's Narrative of the Carceral State” is slated for a fall 2023 release by Haymarket Books.

![]() The first time I was in solitary I was 16. The year was 1994. I'd run from an officer trying to arrest me for violating curfew while on juvenile probation. Once I was caught and returned to a youth detention center in Maine, my punishment for running was being stripped down to my underwear by law enforcement, who then put me into a cell with a thin plastic mat and nothing else. They told me not to talk.

The first time I was in solitary I was 16. The year was 1994. I'd run from an officer trying to arrest me for violating curfew while on juvenile probation. Once I was caught and returned to a youth detention center in Maine, my punishment for running was being stripped down to my underwear by law enforcement, who then put me into a cell with a thin plastic mat and nothing else. They told me not to talk.

Intentionally, I was fed at erratic, odd times. At their whim, staff withheld food, showers and the allotted hour outside of the cell for me and others in solitary. We had no clock. Cell windows were painted over and covered in wire mesh, letting in a dim light. We lost track of day and night.

We listened as corrections officers – grown men – beat a 15-year-old boy because he mouthed off. Through that kid’s open cell door, we heard echoes of their fists on his flesh throughout what was labeled as the intensive control unit.

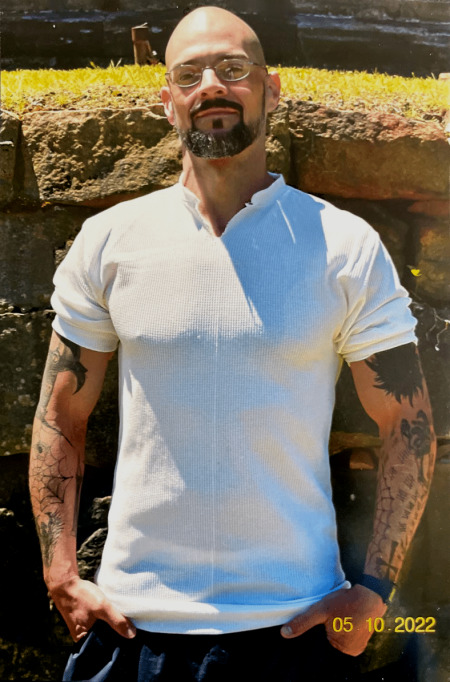

Courtesy of North Carolina Department of Corrections

Lyle C. May at Central Prison in Raleigh, N.C.

Involvement in the juvenile justice system often diminishes one's character, credibility and prospects for redemption, including in the eyes of many jurors and judges who equate a juvenile record with an adult record. In my own and other cases, that juvenile record was used to wrongfully convict me. I have spent years appealing that conviction.

My lived experiences and that of many others prove that juvenile confinement frequently sets youth up to fail. I know why spending $30 million to replace an old jail reserved for 10- through 17-year-olds with a new one – as Durham County Commissioners in North Carolina have unanimously voted to do – will not automatically change what happens on the inside of such a facility. I know why it will not automatically better the lives of young people who wind up there.

For almost 25 years, I’ve been on North Carolina's death row. The people on death row who have signed onto my letter protesting that new jail – and more than 40 other men on death row who wanted to sign but were physically unable to position themselves to do so – were confined as children to boot camps, reformatories, detention centers and youth prisons. We have been on juvenile probation, in solitary confinement and/or suffered lasting harm as wards of the state. In virtually every circumstance, the response to delinquent or criminal acts was punitive or reactive, with little or nothing done that was aimed at preventing a future offense – other than extending the threat of more confinement.

In the tough-on-crime 1990s – the era when Washington lawmakers promoted the mythical juvenile “super predator” – billions of dollars were misspent to incarcerate millions of people. A disproportionate number of them were Black, brown and Indigenous and/or poor, just as they are today. Too often they are housed in facilities rendered dysfunctional because correctional system bureaucracies lack oversight and accountability to taxpayers and to the youth in their charge, youths' families and communities.

When people die in jails – whether from overdose, suicide, neglect or excessive force – investigations are hidden from the public, if they are conducted at all. That absence of transparency has, to some extent, been written into law; that turns publicly funded pretrial detainment centers into privately run punishment factories.

Replacing an old youth jail with a new one may be touted as a way of not endangering justice-involved young people. But that does automatically yield changes in how some juvenile corrections employees respond to incarcerated youth over whom those adults have absolute authority.

The physical abuse I witnessed while a ward of the state is not the only abuse I saw or experienced. As a 19-year-old awaiting trial in a North Carolina facility, two guards beat and strangled me while a third watched from the doorway of my cell. When they were done, the fat guard who had choked me with his baton threatened to hang me and claim it was suicide if they "so much as hear a peep."

Both the Maine and North Carolina facilities were closed for good reasons. When the latter reopened, after a makeover and name change, it faced the same problems of abuse and suicide.

In addition, building a new youth jail in Durham County assumes you can find enough qualified people to staff the facility. But North Carolina's correctional facilities are in the midst of a severe and worsening staffing shortage. Too many prisons, not enough qualified people to run them and low wages mean people who should not even be working in these facilities keep their jobs and gain rank and make poor decisions and cut corners, especially in rehabilitative and educational services.

Prison violence is directly linked to understaffing and poor management. Consolidating and closing facilities, releasing people and providing a path to true community accountability are the best ways to improve public safety.

In that vein, the Youth Heal in Communities Not Cages coalition is demanding that the county commission remove youth jail funding from the 2022-23 budget to allow six months for a youth- and community-engaged process of proposing alternatives to youth incarceration that, as examples, would include a wellness center providing a wide range of mediation, therapy and transformative justice services for young people. These alternatives are critical to preventing youth from committing crimes or entering the adult criminal legal system.

Addressing crime means proactively intervening in the lives of troubled youth through intensive mentorship programs in and out of school; substance abuse and mental health treatment; job training; secondary and post-secondary education; and domestic violence intervention.

Keeping youth educated and involved in pro-social activities is important to helping them understand and care about their trajectory and future. Durham County’s leaders must accept their responsibility to give youth a future that they care about, not fear. Regardless of their mistakes, they need access to opportunities. Confinement has never and will never provide that.

Youth need restorative justice approaches espoused by such individuals as Durham District Attorney Satana Deberry and Religious Coalition for a Nonviolent Durham Director Emeritus Marcia Owen. Those approaches aim to ensure that persons who commit crimes take accountability; reach some sort of reconciliation with those they've harmed; and help make those who have been harmed as whole as possible.

There are more effective ways to invest taxpayer dollars than in a new jail. A $30 million building will not guarantee a better, safer community. It will not change youth incarceration that, too often, amounts to a wanton infliction of pain and anguish that discards their potential for growth.