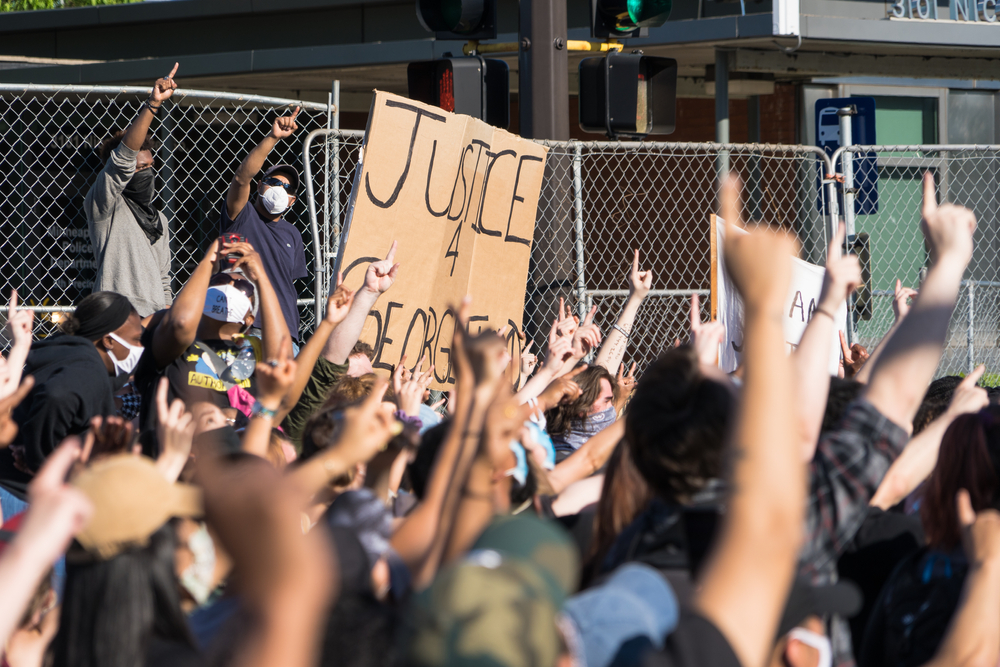

A month after the murder of George Floyd, the Minneapolis school board voted to end its contract with the Minneapolis Police Department to staff schools with armed school resource officers and tasked Minneapolis Public Schools Superintendent Ed Graff with creating a new plan for school safety.

At the time, schools across the country were considering ending the presence of police officers in schools. In Minneapolis, Floyd’s death moved what had been a roughly decade-long conversation into action.

By September 2020, 11 new unarmed public safety support specialists, many with law enforcement-related backgrounds, were in place and on the Minneapolis Public Schools payroll.

Two years and one pandemic later, initial data and interviews with students and staff suggest that fewer Minneapolis students are being punished and, consequently, missing class for suspensions or other punishment. Significantly fewer students are having contact with law enforcement officers due to their behavior at school.

During the 2020-21 school year, when Minneapolis police officers staffed schools, there were nearly 250 instances where student discipline involved law enforcement in some way, ranging from a conversation with an officer to legal action. In the first half of last school year, it happened just 13 times.

But racial disparities in school discipline remain. Black students make up about a third of the district’s student body, but accounted for 70% of disciplinary actions in the first half of last school year.

Courtesy of Micere Keels

University of Chicago professor Micere Keels.

As to whether removing school police officers in Minneapolis and schools across the country has made schools safer, “It’s hard to say in this moment,” said University of Chicago professor Micere Keels, who works with some of the country’s largest school districts on safety and other issues. She has not worked directly with Minneapolis.

Schools nationally reported increases in disruptive student behavior last school year.

But most educators Keels has talked with attributed that to the challenges of the pandemic, rather than some districts’ decisions to remove school resource officers, or SROs, from local schools.

“Yes, at the base level, disruptive behaviors have increased in all schools. But schools that removed SROs are not having a problem managing those behaviors,” Keels said. “They don’t feel like we need to get the police back in schools to manage student behavior.”

Outside Minneapolis’ North Community High School this spring, students said they were concerned about their safety in the wake of the latest school shooting. But junior Lindsay Lewis reacted with a shrug to discussion about replacing the police department’s school resource officers with new safety staff.

“I generally feel safe here,” she said.

“Things are going a lot better”

“Things are going a lot better,” under the new school safety model, one northside high school teacher said. The teacher requested anonymity, fearing potentially negative attention in the wake of a teachers strike in early 2022.

“Our public safety specialist is well known in the community and is friends with my principal who is incredibly well respected in our north Minneapolis community,” the teacher said. The safety specialist “lives in [the district] and sends his own children to our schools.”

Courtesy of Jason Matlock

Jason Matlock is the Minneapolis Public Schools director of emergency management, safety and security.

A central difference between the police department’s SROs and the new safety specialists is the fact that the former work for the school district, rather than the police department, said Jason Matlock, the district’s director of emergency management, safety and security. He oversees the new public safety support specialists.

“The biggest problem MPS had was, if someone feels like a crime was committed and they want law enforcement action, I can talk to them but if they push the [SROs] had no right to say no,” Matlock said. “If a parent showed up and said they wanted to press charges on an eighth-grader who pushed another eighth-grader — as much as we can talk and try to de-escalate — at the end of the day there was nothing we could do” to stop that.

Many of the new school safety staff attended or previously worked at local schools, and Matlock is working to hire more over time. And the new school safety staff are more racially diverse.

“While we sought to have a diverse SRO group, we could only do so much with what MPD had to offer,” he said of the previous set-up. “With the specialists we were able to find excellent candidates that much better reflected the student population.”

By the numbers

While COVID-19 school closures and the pandemic’s far-reaching effects make precise comparisons difficult, preliminary district discipline data suggest that fewer students were disciplined this year than in past years.

“It’s hard to evaluate any system over the last two years,” Matlock said. “Perception and feeling, versus reality, is hard to measure. But, anecdotally, the feedback we’re getting is overwhelmingly positive. The numbers from surveys of students and referral data show that we’re trending in the right direction.”

Minneapolis Public Schools has not yet responded to Youth Today’s July 8 request for data on the number of students who are diverted from suspension, expulsion and other traditional discipline methods to other discipline or responses to their behavior.

Courtesy of Minneapolis Public Schools

“At the moment I don’t think SROs are the most pressing issue students have been dealing with,” said student Kennedy Rance.

However, the data the district has released shows that Minneapolis schools took about 1,900 disciplinary actions against students in the first half of the past school year. Minneapolis schools took about 13,000 disciplinary actions — seven times as many — during the 2018-19 school year, the last full in-person learning year before COVID hit.

Over the past five years, the number of suspensions and expulsions has generally declined. That decline is the result of specific efforts by the district, said Cristin Craig, the district’s interim executive director of equity and integration, and Julie Young-Burns, the district’s social and emotional learning lead.

Those efforts include not suspending students as a consequence for “more subjective” behaviors such as disrespect or insubordination, they said.

Students who would otherwise be recommended for a transfer to another school or expulsion due to their behavior may instead have a “family group conference,” they said.

And school staff have received training aimed at helping them strengthen ties between classrooms and communities; create shared agreements on how students and others at the school treat each other; and help students understand the impacts of their behaviors.

However, while Black students have been slightly less over-represented in disciplinary referrals since school safety staff replaced police officers, each of the nearly 30 students who were referred to law enforcement or recommended for expulsion in the first part of last school year were Black.

“They wanted another way”

“When SROs were present, a lot of students said it made them uncomfortable and that they wanted another way, someone who wasn’t law enforcement, who wasn’t carrying,” said Kennedy Rance, a junior at north Minneapolis’s Patrick Henry High School and at the time a student representative to the Minneapolis School Board. However, “at the moment I don’t think SROs are the most pressing issue students have been dealing with,” she said.

Mental health resources in wake of COVID and the disruption it has brought to students' lives are a bigger concern, she said.

“I feel like the biggest threat to safety comes from students having mental health issues,” said Emi Gacaj, a senior at Southwest High School. “The biggest thing we can do to keep our schools safe is to fund them and make sure that students are feeling OK, accepted and welcomed.”

***

Cinnamon Janzer is a Minneapolis-based journalist.