Citing, among others, the case of a Black boy who first was incarcerated, at 14, for stealing candy and, at 16, died at a restrictive wilderness camp where he was sent for violating curfew and other parole violations, a new report from The Sentencing Project suggests that U.S. courts divert comparatively fewer minority youth into community-based service or other rehabilitation. And diversion, overall, is sought less often than it should be.

Released today, the Sentencing Project’s “Diversion: A Hidden Key to Combating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Juvenile Justice,” analyzing 2019 nationwide data, concluded that:

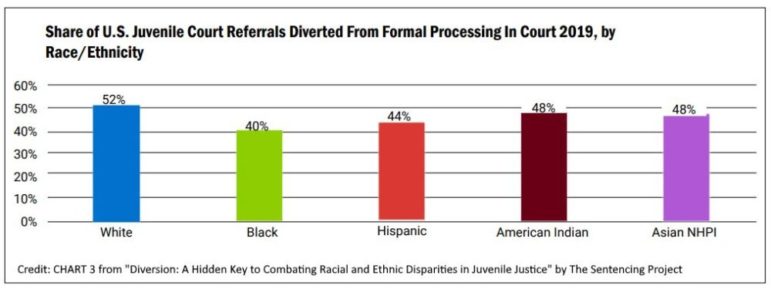

- 52% of delinquency cases involving white youth were diverted.

- 44% to 48% of cases involving Latinx, Native or Asian American youth were diverted.

- 40% of involving Black youth were diverted.

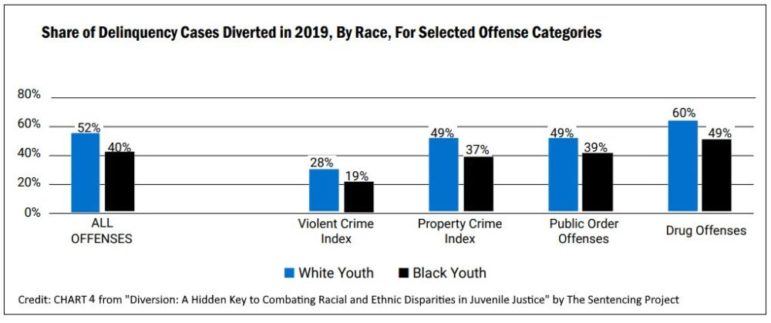

“These gaps,” according to the report, “cannot be explained by the seriousness of offenses youth are accused of committing: glaring disparities between Black vs. white youth can be seen within every major offense category. Over time, these disparities have been getting worse, not better.”

“Kids make mistakes, kids grow out of their mistakes,” Richard Mendel, the Sentencing Project’s senior research fellow on youth justice, told the Juvenile Justice Information Exchange and its sister publication, Youth Today. “And if you don’t interrupt the trajectory of their growth, they’re going to do fine. But if you try to intervene too much, it’s going to produce counterproductive consequences.”

Those consequences include higher risks of long-term involvement in the justice system, he added.

Addressing racial bias in arrests, courtrooms

Central to changing what now is a racially disparate and under-used diversion system, Mendel wrote in the report, is mandating training of court officials to recognize and reverse their biases.

“The case files of Black youth had six times as many critical comments about the young people’s characters (such as ‘feels no remorse,’ ‘does not take offense seriously’ or ‘uncooperative with justice officials’) as those of white youth,” according to the Sentencing Project, which extracted those examples from a 2021 study of Arizona diversion courts.

The Sentencing Project’s analysis further concluded that 46%, overall, of juvenile cases were diverted. (By comparison, among other nations that divert, the rates were 75% in Denmark, 80% in Belgium and 83% in New Zealand.)

Given that 7% of cases landing in family and juvenile courts involved serious violent offenses, far more cases should be diverted, Mendel said. The remaining 93% of juvenile cases involved trespassing, shoplifting, simple assault, truancy, underage drinking and other non-violent offenses that generally posed no threat to public safety.

There are two forms of diversion: Pre-arrest diversions where authorities decide not to involve police, make an arrest or send a case to juvenile court. And pre-court diversions, where prosecutors or court staff can choose not to formally petition for allegations to be tried in court.

Diversion can include a range of programming. Among them are family counseling, mental health counseling, job training, education courses and victim awareness activities.

Absent diversion, some punishments are needlessly harsh

Youth of color, from the outset, are arrested at disproportionately higher rates than whites, which is a critical factor. “The lack of diversion opportunities for youth of color is pivotal because greater likelihood of formal processing in court means that youth of color accumulate longer court histories, leading to harsher consequences for any subsequent arrest,” Mendel wrote.

“Diversion,” Mendel told JJIE, “has gotten so little attention, even though it’s so important to what happens and what works in juvenile justice.”

In citing the case of Del’Quan Seagers, the 16-year-old who died in 2015 at a South Carolina wilderness camp, Mendel noted how that simple case of stealing candy escalated. The boy, whose father had been murdered two years before that infraction, was placed on probation, instead of diverted.

When he broke probation rules, he was sent to a wilderness camp facility for three months. He was released and received no violations for more than a year, but then was sent to another camp for skipping school and violating his curfew. He died there, purportedly of an asthma attack, a claim disputed by other young people who were incarcerated at that camp.

In addition to addressing implicit biases of police officers, court staff, prosecutors and judges, the report also advocates expanding pre-arrest diversion and eliminating prohibitions of pre-court diversions for any arrests beyond a youth’s first, arguing that it will counteract the existing higher arrest rates of young people of color.

The report calls for the elimination of common practices that perpetuate racial disparities, including penalties imposed for not paying fines and court fees that some families cannot afford. It calls for changes to how court officials treat single-parent households and relatives who are primary caretakers of youth.

Courts, Mendel told JJIE, should be reserved for the fraction of cases involving juveniles who appear to pose a serious threat to others.

“We should use it sparingly,” Mendel said. Too often, “it makes things worse, and that understanding needs to pervade the society.”

***