Videographer Jacob Langston/For JJIE

Rion Schofield was selling drugs at 13. By age 15, he was carrying a gun.

“I was riding my bike and breaking into cars and came across my first one,” he said. “Eventually, over time, I had quite a few. Double digits.”

Firearms were for protection, he said. “It made you feel safe. When you’re living that kind of lifestyle, you always want to be protected.”

He got caught up in the juvenile justice system. Then, when he was not yet 20, he went to prison for dealing in stolen property. A few years later, he was incarcerated again, this time for second degree attempted murder with a gun.

Courtesy of Rion Schofield

Rion Schofield, left, participates in a St. Petersburg, Fla., anti-violence campaign.

“A drug deal gone bad,” he said.

In May, the St. Petersburg, Florida, resident returned home determined to steer young people away from the path he had traveled.

But Schofield’s resolve runs up against a new study that finds handgun carriage by adolescents has gone up significantly over the past two decades.

The jump — 41% — was especially pronounced among rural, white, and higher-income adolescents, according to the study, which was published by the American Academy of Pediatrics. The study was based on nationally representative surveys conducted annually from 2002 to 2019 of about 300,000 12-17-year-olds.

“The big finding was that [gun] carriage increased substantially. That translated to hundreds of thousands of adolescents,” said Naoka Carey, a co-author of the study and a doctoral candidate at Boston College.

Courtesy of Naoka Carey

Naoka Carey

However, the way the gun law landscape has changed over time may have shifted the dynamics of youth gun carrying and the characteristics of youth who choose to carry guns, said Kelly Drane, research director for the Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence.

“Since 2015, for example, there have been 20 states that have completely eliminated their concealed carry permit requirements and now half the states have permitless carry laws. So it’s reasonable to think that some of these cultural norms around gun carrying — and also just the fact that more people are carrying guns — may make guns more accessible to children and then make young people more interested in carrying a gun.”

Currently, the vast majority of American gun owners are white, Drane said. “And so, I think it’s reasonable to believe that white youth may be more easily able to access guns in the home,” she said

The American Academy of Pediatrics study captures the extraordinary surge in gun-carrying by adolescents, said Dr. Eric Fleegler, a pediatric emergency physician and health services researcher at Boston Children’s Hospital and associate professor at Harvard Medical School.

“Attitudes towards having guns have changed toward the more the better,” Dr. Fleegler said. “And that guns infer protection as opposed to a safety risk. But epidemiological evidence shows there’s actually increased risk.”

As for evidence of increasing carriage by wealthier kids, he noted that, “contrary to the data that living in poorer areas is a higher risk factor for firearm fatality, owning guns still costs money. We know that in studies with adults, there are higher gun ownership rates with higher incomes.”

The American Academy of Pediatrics study found that about 7% of American boys and young men reported carrying a handgun at some point in the previous year.

“The simple math tells you that roughly one in 13 adolescent males is carrying a firearm over the course of the year,” said Dr. Fleegler. “It should be noted they are under the age where they can legally purchase a firearm. In other words, they are either being given these guns by family or friends, they are taking them from family or friends, or they are illegally obtaining these guns.”

[RELATED STORY: "Study: More girls are carrying guns"]

Most teenagers who carry handguns are doing so illegally: Under federal law, you must be 21 to purchase a handgun from a licensed dealer, but in many states, individuals can purchase a handgun from an unlicensed seller at age 18. However, most minimum age laws include exceptions for minors who are participating in shooting sports, doing agricultural work, or carrying on family property with their guardian's permission.

In Volusia County, Florida, which stretches from the Orlando exurbs through rural areas to Daytona Beach, Sheriff Michael J. Chitwood blamed easy access to firearms for increased gun violence by both young men and young women.

While kids are stealing guns from vehicles and buying them on the internet, Chitwood said they’re also getting them from their parents, “where mom and dad go away and the kids have a party at the house and then six guns are missing.”

And in the city of St. Petersburg, the Rev. Kenny Irby, community intervention director for the St. Petersburg Police Department, said the city is seeing a lot more guns in the hands of juveniles, both girls and boys.

Officials know, “through conversations with the Department of Juvenile Justice and other agencies, that St. Petersburg is not in some type of isolation,” he said.

“Kids tell you that they need guns to protect themselves. They also say they need the gun for the power that a gun brings. So, the perceived power. And then, the prominence.”

A heavy cost

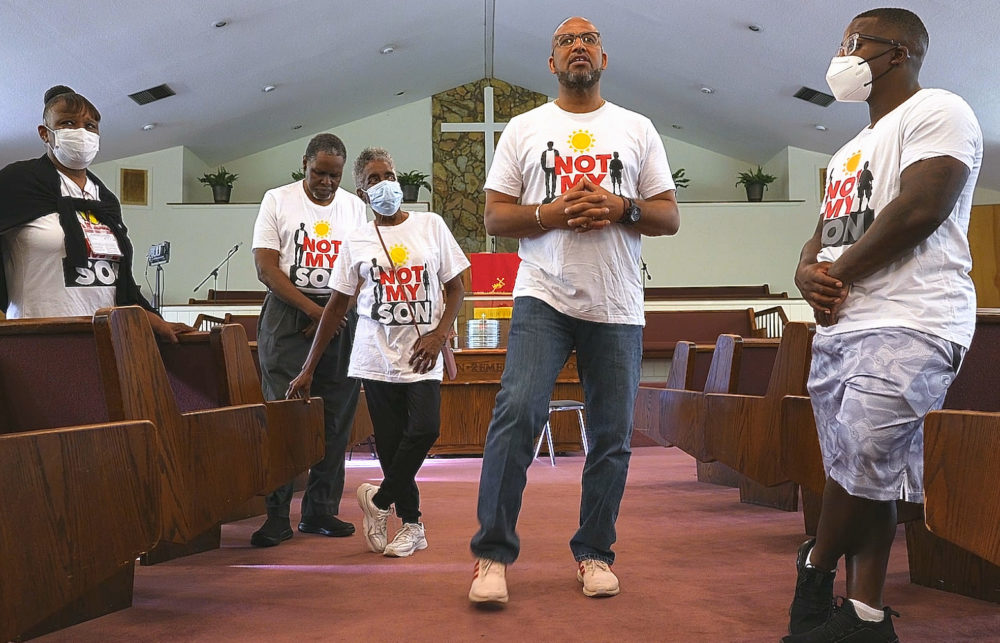

Jacob Langston/For Youth Today

The Rev. Kenny Irby, community intervention director for the St. Petersburg Police Department, speaks with participants in the city's Not My Son anti-violence campaign.

It all comes at a heavy cost.

Dr. Nina Agrawal, a pediatrician, sees that in her work with youth in the South Bronx, in New York City. She chairs the American Medical Women's Association’s Gun Violence Solutions Committee. Earlier this year, the committee collected hundreds of signatures from healthcare professionals asking Health and Human Services Secretary Xavier Becerra to declare gun violence a health emergency for America’s children.

“What I’m seeing in my patients are kids who often have friends who have died, or peers who have died from gun violence and children and youth that are afraid in their own neighborhoods because of gun violence outside their homes and on the streets,” Agrawal said.

Her patients don’t speak about owning guns themselves, but know others who do, she said.

Gun violence is detrimental to children’s development, she said. “I think it's damaging to youth and especially Black youth who have lived in impoverished communities who don't have opportunities or resources. So, exposure to gun violence, compounded with all those adversities, increases the risk of victimization and perpetration, like gun carrying.”

The firearm homicide rate among Black males aged 10 to 24 was 20.6 times as high as the rate among white males of the same age in 2019, according to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the ratio increased to 21.6 in 2020.

While the overall firearm suicide rate remained relatively unchanged between 2019 and 2020, the firearm suicide rate for young people and some racial and ethnic minority groups did increase; the highest increases were among American Indian and Alaska Native persons.

And firearm homicide and suicide rates are higher in the poorest areas of the country compared to the wealthiest: "In 2020, counties with the highest poverty level had firearm homicide and firearm suicide rates that were 4.5 and 1.3 times as high, respectively, as counties with the lowest poverty level,” according to the CDC.

The American Academy of Pediatrics study found that the percent of white male teenagers reporting carrying a handgun at least once in the past year jumped from 4.9% to 8% between 2002 and 2019. For wealthier males nationally, the increase was 4% to 8%, and for wealthier females nationally, 1% to 2%, during the same period.

However, the rate of firearm fatalities has increased for Blacks and Hispanics at a steeper rate than for white youth, said Dr. Fleegler, one of the authors of a recent study on trends and disparities in firearm fatalities.

“Not only have these rates gone up, but the disparity has worsened. While carrying a gun is certainly a risk factor for being shot and killed, living in a poor neighborhood, a neighborhood with higher unemployment, and a riskier environment is a much greater risk factor for being killed by a gun than simply the statistic of gun carrying rates,” he said.

Having access to guns is particularly dangerous for teenagers because they are naturally impulsive, said Dr. Brandon DeLiberato, medical director for child and adolescent psychiatry for BayCare Health System in Tampa.

Courtesy of Travis Maus

Capt. Travis Maus

“The part of the brain that helps you make good decisions is not developed,” he said. Full brain development doesn’t take place until about age 26, he said.

Social media posts can exacerbate those factors, said Capt. Travis Maus, head of the Violent Crimes Bureau for the Tampa Police Department.

“A lot of gang issues do result from social media,” he said. “They play tit-for-tat videos and it will end up with somebody getting shot.”

Dr. Juan Carlos Abanses, medical director of the Steinbrenner Children’s Emergency Room at St. Joseph’s Children’s Hospital in Tampa, has seen the results of more teenagers carrying guns.

“We've been seeing more of other people accidentally injured from kids kind of taking out a gun. They get mad and try to get one person” and a bystander is shot, he said.

“They want to see something change”

In Kansas City, youth outreach center director Juan Tabb regularly talks with teens who are concerned about gun violence in their neighborhoods.

Courtesy of Juan Tabb

Juan Tabb

“They want to see something change,” said Taub, executive director of ArtsTech. “In Missouri, we have very lax gun laws. You can go to a sporting goods store and purchase a handgun and walk out of that store with a handgun in less than an hour. In Kansas City last year, we lost 25 youth to gun violence. That’s approximate. That number, to me, is staggering.”

Tabb pointed to Kansas City, Missouri, police data for 2021 showing 15 homicides of youth 17 and younger and 30 for those ages 18 to 24.

Damon Daniel is president and CEO of AdHoc Group Against Crime, which operates in the Kansas City metropolitan area. The organization’s wide-ranging services include working with hospitals on a violence intervention program.

“The interesting thing about youth, particularly in the situations we find them, they are not forthcoming with information,” he said.

Courtesy of Damon Daniel

Damon Daniel

“A lot of them don’t know what they need. Sometimes, if the incident happened at home and if it is someone who knew them, the request for relocation comes up, unless that person has been apprehended. It really depends on the situation. Some are not even willing to participate or talk. Some of that could be fear, or in some cases, it’s mistrust, which is understandable … In some cases, they might not have been the intended target,” Daniel said.

Since he returned home from prison, Schofield has been volunteering with gun violence prevention efforts. Over the summer, he worked with Irby on St. Petersburg’s Not My Son campaign, begun in 2016 after seven young Black men were shot and killed within two months during the previous year. The campaign is a collaboration of the interfaith community, law enforcement and residents who walk through neighborhoods that have suffered from gun violence. They encourage residents to become proactive, responsible parents and young people to commit to non-violence.

The effort focuses primarily on African-American youth and young adults, ages 12 to 24. Each Friday during the summer, canvassers meet at a host congregation or city recreation site, where they start the evening outreach with prayer. Then they split up to knock on doors in the surrounding neighborhood. They tell residents about special educational and mentoring programs for youth and young adults that focus on teaching life skills and conflict resolution without firearms. Those who are approached are invited to show their commitment to violence prevention by placing Not My Son signs in their yards and signing pledge cards. Young people pledge to “never use a weapon to resolve conflicts.”

Schofield offers advice to the area’s youth.

“I try to encourage them to focus on bettering themselves every day and not worry about the outside forces,” he said.

***

Waveney Ann Moore is a St. Petersburg-based journalist who covers diversity and equity issues.