This story was originally published by MLK50: Justice Through Journalism. Subscribe to their newsletter here.

In the memory, she is 8 years old, prettied up in barrettes and beads and new clothes, fly-girl fancy. She stands in the sunshine, preparing to step from a Knoxville sidewalk into a family friend’s car. Driver and passenger are about to road-trip from eastern Tennessee to South Florida.

Jameerial Johnson, now 24, wonders still how her little girl self would have looked in her father’s adoring eyes on that day more than 15 years ago.

“I just wanted him to see my hair. It was braided, with little curls hanging down the sides. I was going to the beach. And I wanted him to see me.”

He, though, was on the other side of the Cumberland Mountains. There was no way he could catch sight of her.

When her father, Almeer Nance, was 16, he was sentenced to a minimum of 51 years and, after that, another 25 years for abetting a robbery of a Knoxville Radio Shack and being an accomplice to the murder of store employee Joseph Ridings, 21. The shooter, then-19-year-old Robert Vincent Manning, was sentenced to life without parole.

His participation in that 1996 crime, Nance said in a 2022 Al Jazeera documentary, was an egregious mistake by a mindless kid with an absent, alcoholic father and a single mom who, at the time, was addicted to cocaine. He’s also said that he’d feared Manning, a white acquaintance whom he knew to be dangerous; Manning had shot one of Nance’s friends earlier on the day of that Radio Shack murder-robbery.

“He had no idea it was going to turn out the way that it did,” Amanda Jo Goode said in the same documentary, which examined Tennessee’s long sentences for youth, the nation’s harshest. Goode, then 16, also had ridden to that Radio Shack in Manning’s car. Unlike Nance, a Black man, Goode is white — as were the prosecutors, police, judge, Nance’s defense attorney and most of the jurors in Nance’s case. She spent one year behind bars.

Nance’s daughter knows the details of her father’s crime. She’s endured the constant emotional churning of having a father who’s been incarcerated for her entire life, who’s missed every school event, scraped knee, birthday, young adult accomplishment, intermittent bouts of depression, garden-variety failure, almost everything.

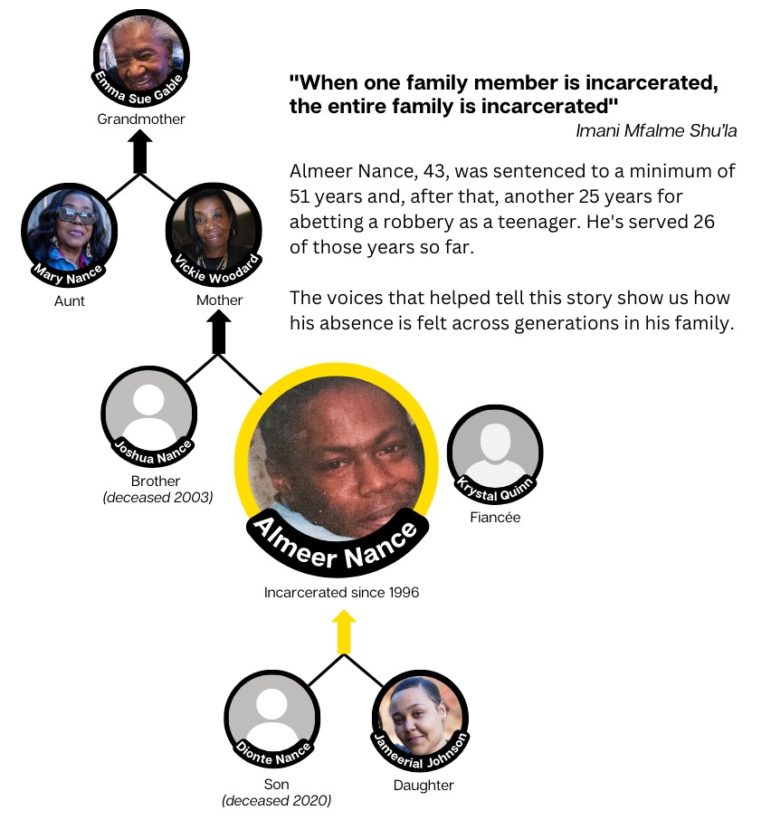

For her, his everyday absence has extracted something precious and irretrievable. That’s true for Johnson and the other women — Nance’s mother, grandmother, auntie, sister, fiancée — who are among the 43-year-old prisoner’s staunchest supporters in his ongoing fight for not just freedom but something approaching an exoneration. That battle started immediately after he was convicted in 1996. It ratcheted up when he applied last year for gubernatorial clemency. Chiefly, it requests that his two consecutive sentences run at the same time, making Nance, incarcerated for 26 years now, eligible for parole in 2028.

As she’s followed the details of her dad’s fight for release, Johnson, a certified nurse’s assistant, also has celebrated his joys and triumphs. Like being there on an afternoon in October 2022 when he walked across a makeshift graduation stage, “Pomp and Circumstance” blaring over the public address system at Tiptonville’s Northwest Correctional Complex in west Tennessee. Like hugging him and being hugged back, tightly, after Northwest’s educators and prison officials shook Nance’s outstretched hand, gave him his associate degree, then posed alongside him for a congratulatory photo.

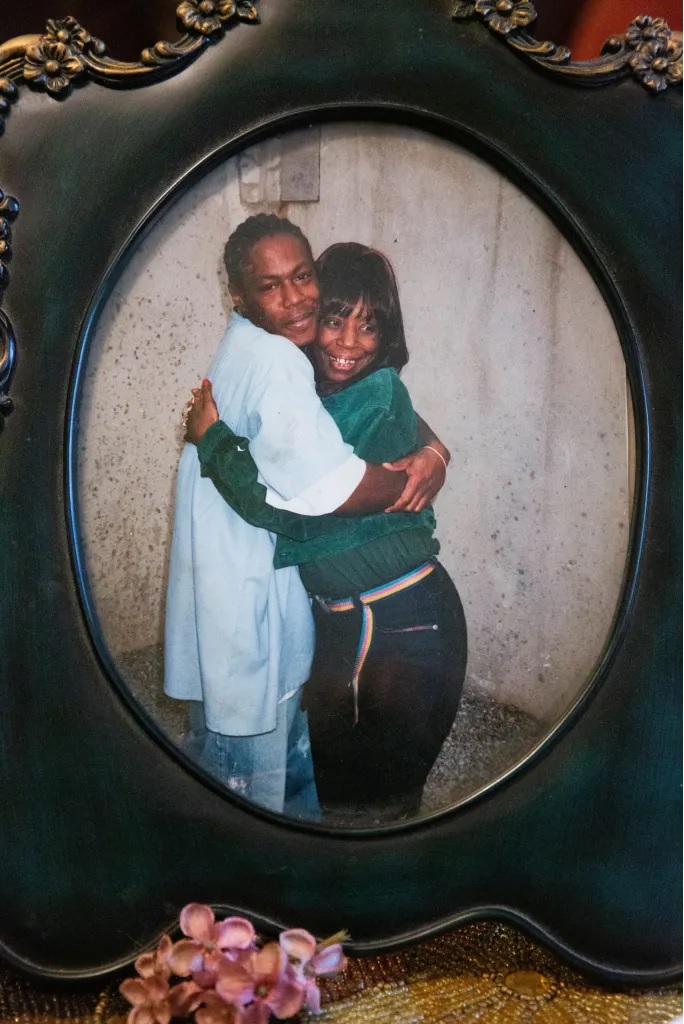

Jessica Tezak for MLK50

“It breaks you down to your very core, mentally and physically. Like a part of you is missing,” Vickie Woodard (right) said of having a child in prison.

Those women whom Nance considers the singular beating heart of his past, present and future — whatever lies ahead for him — say they strive to keep in view his touchstone achievements. (He’s now working toward a bachelor’s degree). They are inexpressibly glad to see, listen to, while away visits with him in that prison town of 4,000 residents, even though those hours are excruciatingly brief and confining.

“You can only hug and kiss on arrival and when you leave. Other than that, there is no physical contact,” said Krystal Quinn, 46, Nance’s fiancée.

That barrier, but also being separated by the 400 miles of interstate, two-lane highways, small towns, big city Nashville and snatches of the mountains between Tiptonville and Knoxville, can make positivity an elusive thing.

“There’s a lot of grief and a lot of sorrow,” said Vickie Woodard, 67, Nance’s mother, sitting recently alongside her own mother, sister and granddaughter in the living room of her suburban Knoxville home.

“You never get no peace,” Woodard said. “It’s like a part of you is locked up. There are times when you feel like you’re OK, but then, you have them moments when you lay down at night and a part of you is missing. Basically, you’re doing time, too.”

A chance to be free?

Jessica Tezak for MLK50

Vickie Woodard (second from left) holds a portrait of her son while standing with Mary Nance (left) Jameerial Johnson and Emma Sue Gable. Almeer Nance is serving 51 years in prison for being present at a murder when he was 16 years old.

Uncertainty and contemplated, tempered expectations run parallel for the women and for Nance, Tennessee Department of Corrections Prisoner No. 00312561.

When, by a 3-to-2 vote, the Tennessee Supreme Court outlawed mandatory life sentences for minors, calling them cruel and unusual punishment, Nance was partly jubilant, partly cautious. “There is a certain amount of joy and ease and optimism that comes into play,” he told MLK50, in a phone call. “But you also have to look at this from a place of, ‘What exactly does this mean?’”

He’d settled on his own more thought-out answers a few weeks later, as he was requesting letters to support his clemency request from prison officials and assorted players outside of prison. “Now that things have changed, I have supreme confidence. I think there is a 100% likelihood that I will be free. ‘That which you say, so shall it be.’ If I speak positivity into the universe, the universe will deliver that back to me.

“This situation has been my foundation, my purging, my schooling, my cleansing.”

Those convicted as minors, according to that ruling from the state’s highest court, must be offered the chance at parole after a minimum of 25 years behind barbed wire and bars.

“But it’s not clear to me whether that will happen automatically or whether courts will have to enter in new cases,” said Jonathan Harwell, an assistant public defender in Knox County, adding that Nance likely would be covered by the ruling if his two sentences were concurrently served.

Harwell has argued before the Tennessee Supreme Court that the state’s 1995 law allowing minors to be tried as adults and sentenced to a mandatory 51 years if convicted of felony murder defies humanity and reason. Minors should be sentenced based on individual circumstances, not mandates aimed merely, squarely at punishing, he said, citing multiple studies concluding that teen brains aren’t fully developed and don’t readily allow for kids to control impulses. (Other researchers have challenged that science.)

Those convicted as minors who are serving life without the possibility of parole or those given additional, consecutive sentences atop a life sentence may have to further litigate to benefit from the November ruling, Harwell added.

Indeed, additional litigation may be required to refine the ruling, said Imani Mfalme Shu’la, lead organizer of Community Defense East Tennessee and a national trainer for San Jose, California-based De-Bug. Its participatory defense model teaches defendants, their relatives, friends and other supporters how to build a presumably winning argument in court.

If any convictions of juveniles tried as adults should be overturned, Mfalme Shu’la said, Nance’s should be among those at the top of the list, especially given the difference in how he and Amanda Jo Goode were treated in court.

“Almeer,” Mfalme Shu’la continued, “was locked up with a guy I knew growing up. The guy got out and inboxed me: ‘I was in with this guy. His case is compelling.’”

Nance, at first, didn’t think she’d fully grasped his case, telling her, “‘No, you’re not really listening to me. My case is different,’” she said. “He made me stop and hear him … He went into the details. I was, like, ‘Whoa, wait a minute.’ The white girl got less time, though neither of them committed the act … Listening to Almeer articulate all of it forced me to ask, ‘How do you want us to support you?’ He says, ‘I just want people to hear my story’ … And the way he tells it, the nuance, the disparities, the good, the bad … the truth … ”

Her voice trails off. Mfalme Shu’la’s father spent two decades in prison. Four of her five brothers have been incarcerated. She is the guardian of her nephew, the son of one of two brothers who are currently imprisoned.

“When one family member is incarcerated, the entire family is incarcerated,” she said. “There is no way I can replace, pay my nephew what it cost him to have his father gone. I can’t even describe what that is,” she said.

“But I am so present in his life. Because I am trying to minimize what I call the collateral damage he suffers by knowing his father is alive but not here.”

The toll on kin

Jessica Tezak for MLK50

Woodard sits in the living room of her Knoxville home.

In “Who Pays: The Hidden Cost of Incarceration on Families,” a 2015 report commissioned by the Ella Baker Center for Human Rights and Forward Together, researchers broadly concluded that “overwhelming debt, mental and physical ailments and severed family bonds … are some of the hidden consequences of incarceration in the United States.”

In a 2019 report, the Prison Policy Initiative concluded that, nationwide, families of those who are incarcerated annually spend $1.6 billion adding money to their incarcerated loved ones’ commissary accounts and $1.3 billion on telephone calls.

On one of the several private attorneys she’d hired to handle legal appeals for Almeer Nance, back then, Woodard said she spent $40,000. She didn’t keep a running tab of what all the lawyers got.

“We done had lawyer after lawyer after lawyer,” she said. “We been beat out of a lot of money. Put it like that. What went wrong was making that big bond. Instead of making that big high bond, paying all them thousands and thousands, we should have put that money toward getting a real good lawyer.

“But I was young, I didn’t know no better. And no one in our family had been in trouble like that before. ”

During the first two years of her son’s incarceration, she’d spiraled.

“It affected me mentally and physically, to the point where I had to get on medicine. I couldn’t sleep. I couldn’t get no rest,” said Woodward, an employee of a Knoxville manufacturer of military uniforms. “He was just a kid, maybe 90 pounds, not more than 105. But I just use that as a figure of speech.”

It’s hard for a loving mother not to fixate on her imprisoned child’s well-being. Nance’s wellness is one of the matters preoccupying Woodard during what always have been anxious seven-hour treks, by car, to Tiptonville.

Her now ex-husband used to do the driving. Since the couple’s breakup, she’s visited Nance slightly less often. Their mother-son telephone calls, however, are more frequent. Hearing his voice quells her concerns over whether he remains of sound mind, healthy and safe. Tennessee’s corrections agency officially lists Nance as 5 feet 8 inches tall and 140 pounds, smaller than many of his fellow prisoners.

Prison can be an intrusive, intimidating place, including for the visitor, Nance’s daughter said: “Before COVID hit, you’d have to go in, get processed, go through the little metal detectors. They take you in the bathroom, one by one, pat you down, run their hands over your pants and through your waistline and under your bra … I had some lace around my underwear once and [the corrections officer] didn’t want to let me in. I said, ‘I’m going to see my dad, not my man. Why does it matter?’

“Sad to say, this is normal for me. I’ve been doing it all my life,” added Johnson, who was conceived during the year her father was out on bail and awaiting trial.

Woodard started taking Johnson and her half-brother, Dionte Nance, Almeer’s son, to Tiptonville when they were wee-bitty things. “They’d just play with their daddy in the prison, where there isn’t much for them to play with, just a little box of things,” Woodard said. “I wanted them to know who their daddy was.”

Dionte Nance, then 26, died two years ago in a motorcycle accident. The Department of Corrections didn’t grant Nance permission to attend the funeral. Earlier, during Nance’s sixth year of incarceration, they’d also refused to let Nance attend the funeral of his little brother, Joshua Nance. At 19, he was shot dead in Knoxville.

By his side

Jessica Tezak for MLK50

A sign reads “Love is not only a sentiment, but also an art.” in Mary Nance’s kitchen during a family meal at her and her mother Emma Sue Gable’s home in Knoxville, Tenn.

“I pray to the Lord about it,” said Emma Sue Gable, 88, Nance’s maternal grandmother.

Also seated in Woodard’s living room that recent weekend afternoon, she was summing up her approach to her grandson’s incarceration, which pains her so greatly that a reporter can’t persuade her to talk about it. She’s not visited him in prison for at least 20 years.

“I don’t have time for my mind to be running. I don’t have much of a mind as it is,” Gable said.

“And I miss him,” said Mary Nance, 69, Nance’s aunt. “I miss him all the time, every time I go to my kitchen stove.”

Her nephew was among the boys of her extended clan who’d place blackberries, sugar, eggs and whatnot in a bowl she’d find on her kitchen table some evening after work. He’d want a cobbler. “And he loved my bean burgers,” she said. “That’s just pork-and-beans and hamburger on light bread.”

Years back, he’d told his auntie what he wanted to eat when he became a free man. “‘When I first step foot out of prison, I want a bean burger and an egg custard pie, the whole pie all to myself,’” she said, repeating her nephew.

“I know he’s coming home one day,” Johnson said, of her dad. “Something has got to give at this point.”

“I had just about gave up. It’s just been so long” since it seemed that any momentum was building on her boy’s behalf, his mother said. In particular, she cited the Al Jazeera documentary thrusting her boy into a different kind of spotlight. She hopes it will pick up steam, buttressing Nance’s case.

Should he never get out of Northwest, “I would stay by his side,” said fiancée Quinn, who works at a factory making hospital sanitary wipes and owns a weekend boutique selling her homemade bath and body potions.

“I don’t look at him as incarcerated. I look at him as a whole person,” she said of Nance, who has used what he’s learned in his college business courses to help her build that boutique. It’s one of their topics via telephone and in-person in Tiptonville, where his favorite snacks from the prison vending machine are iced tea, honey buns and Rice Krispies Treats and hers are popcorn or chips and Grape Crush soda.

“When we are together, we make the most of it. We laugh, we cut up. I’ve been married before. I’ve never been with a man like him, who has never asked me for anything. He is positive and supportive. He’s made me a better person. If he can still be happy and have faith, my situation is very OK. I can ride this out … ”

Nance says he knows he’s beloved by these women. He strives not to take them for granted, he said. He cannot fathom the blows and gashes they’ve sustained. He cannot know what it takes to bounce back, to bind the wounds that result from navigating the empty places and what-ifs of his existence.

“My being in here has cost them a lot,” he said, noting the tangible outlays and the ephemeral ones. Throughout the years, his mother has tried mightily to send $50 to $100 a month to cover Nance’s prison commissary purchases. “Just imagine, over the course of 26 years, doing that,” he said. “Initially, it was nothing to have someone accept a collect call. But that runs out.”

More than money spent, his prison stay has meant, for them, “not having a true son, a true brother, a father right there to confide in or what have you … ”

He paused, then began again. “When they come here, they get these small moments and pieces of me. I get small bits of them.

“Then, they have to leave.”

***

Katti Gray is an editor for Youth Today and the Juvenile Justice Information Exchange. She specializes in health and criminal justice news and coordinates national journalism conferences and fellowships for the Center on Media, Crime and Justice at John Jay College and the Association for Healthcare Journalists. She shares a Pulitzer Prize with a team from Newsday and has served as a committee juror and chairperson for the Pulitzer Prize committee.