When, at 19, he was sent to an Upstate New York prison, said Vidal Guzman Jr., corrections officers intermittently locked him in isolation, away from other prisoners and with limited time outside that cell.

“Solitary confinement tried to break my soul and whatever was left of me after my childhood trauma,” said Harlem, New York, native Guzman, now 30, the founder and executive director of America on Trial, a New York group that advocates for incarcerated people.

While in solitary, corrections officers sometimes refused to let him shower or made him forego being fed whenever he wasn’t at the opening of the doorway of his solitary cell when a meal arrived, added Guzman.

“I think it’s simple,” he continued. “How do we want to return people back to society? Damaged or prepared? That is the way you look at solitary confinement and you introduce programs and legislation from there that will return us back better.”

That ethos drives an ongoing effort to ban or, at least, severely restrict solitary confinement of juveniles.

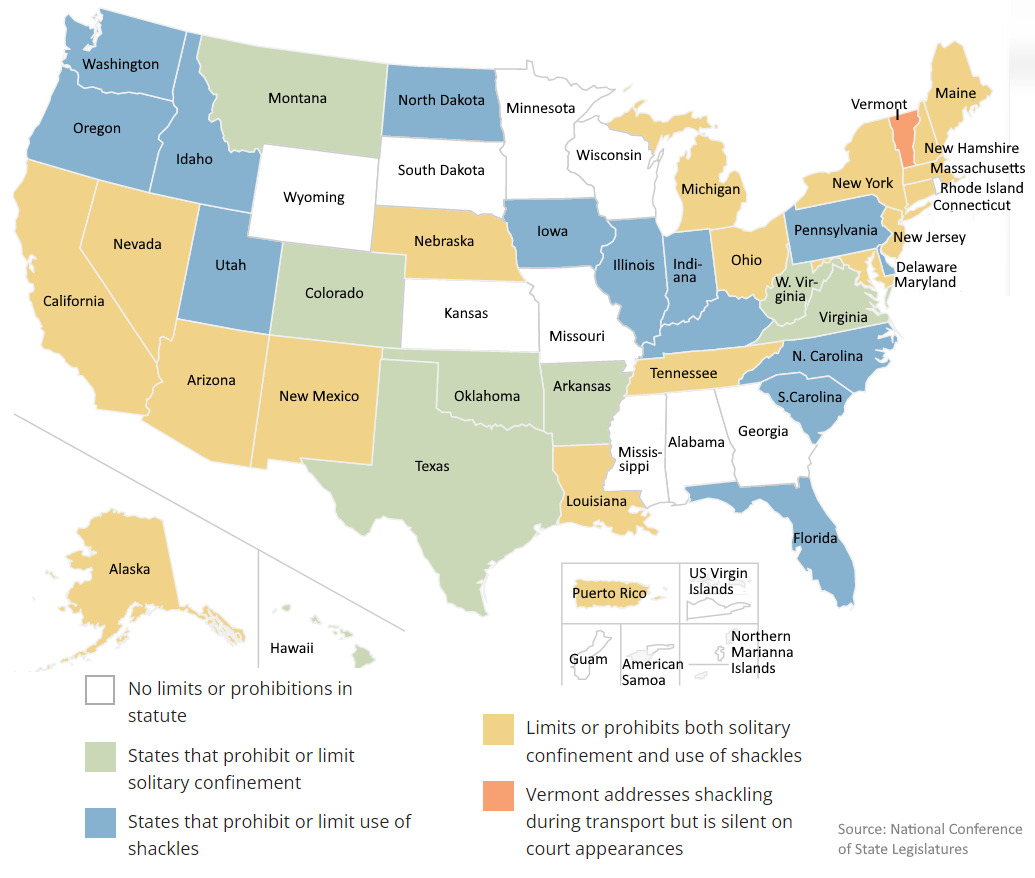

Around the time that then-President Barack Obama outlawed solitary confinement of juveniles in federal correctional facilities in 2016, nine state legislatures banned the practice that critics contend does more to trigger or worsen mental illness in detainees than to rehabilitate them. As of April 2023, 11 states had no limits on the use of solitary confinement for juveniles, according to Anne Teigen, juvenile justice portfolio director at National Council of State Legislatures.

Alabama, Georgia, Kansas, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Rhode Island, South Carolina, South Dakota, Wisconsin and Wyoming "had no statutes, administrative or court rules limiting or prohibiting solitary confinement for juveniles," Teigen wrote in an email to Juvenile Justice Information Exchange.

Alabama, Georgia, Kansas, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Rhode Island, South Carolina, South Dakota, Wisconsin and Wyoming "had no statutes, administrative or court rules limiting or prohibiting solitary confinement for juveniles," Teigen wrote in an email to Juvenile Justice Information Exchange.

“Currently, just under half of the states and the District of Columbia have passed laws that narrow the use of solitary confinement in juvenile facilities,” said Kate Bryan, a National Conference of State Legislatures policy associate. “Other jurisdictions have limited its use in the juvenile setting either through court rules, policy or administrative code."

Trends in solitary confinement for juveniles

At a time when overall crime has declined but gun-related and other violent crimes have surged among youth and young adults, the practice has its supporters — including some correctional professionals, citing what they say is sometimes extreme misbehavior behind bars — and its detractors. Critics of solitary confinement decry, for example, the disproportionate number of Black males being placed in solitary in some states.

As reformers advocate for those remaining 10 states to ban solitary confinement of juveniles and for stricter enforcement of limits on solitary that are in place, they cite what researchers say are the dangers of being isolated while behind bars. Isolation of juvenile offenders, including those deemed especially violent or disruptive, raises the risks of suicide and other self-harm, critics argue.

Richard Ross/Juvenile In Justice

Juvenile solitary confinement cell.

“We know from data and experience that being in isolation — no matter the reason — is dangerous for young people,” said Jennifer Lutz, staff attorney for the Washington, D.C.-based Center for Children’s Law and Policy.

Lutz’s center, the Justice Policy Institute and Council of Juvenile Justice Administrators comprise Stop Solitary for Kids, a national campaign housed at the Georgetown University Center for Juvenile Justice Reform.

"Confinement of youth is banned in federal correctional facilities ... except in a small number of cases and, even in those cases, cannot last beyond three hours," Lutz wrote in an email.

The federal government only oversees juvenile cases from Washington, D.C., and Native American reservations.

A 2009 U.S. Department of Justice report on youth suicides found that more than half of suicides in juvenile facilities in the study’s four-year period occurred when the juveniles were in what researchers described as isolation, segregation, time-out or a quiet room.

“The reason they are in isolation is a factor, but the much larger concerns are the risks of isolation itself,” Lutz said.

The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and American Academy of Pediatrics have argued that isolating youth undermines their rehabilitation process. opposed solitary confinement of youth. The Council for Juvenile Corrections Administrators offers a toolkit aimed at limiting the use of confinement.

“Alone & Afraid,” an American Civil Liberties Union report on putting juveniles in solitary, concluded that the practice harms youth psychologically, stunts their emotional development, raises their risks for self-harm, and is especially detrimental to youth with disabilities and those with a previous history of trauma.

Federal rules

In 2018, federal law required states to submit data to the federal government on the use of restraints and isolation. It also required states to describe their strategies to reduce isolation and federal training and technical assistance to support these goals.

“Proponents argue that isolation can be necessary for the safety of staff, other residents, and for the security of the facility,” said Ryan, of the state legislatures’ organization.

Solitary confinement doesn't help rehabilitate those who are placed in it, said activist and former incarceree Guzman. Rehabilitation, when it happens, often takes place through programming outside of prison, he said. His savior, he said, was the Alternatives to Violence Project-USA, which promotes connection to community, including one’s neighbors, above isolation.

The project, said Guzman, “ ... taught me how to have conversations without resorting to violence and how to resolve conflict.”

***

Patrick Riley is a New Jersey-based broadcast and online journalist and author.

This story was corrected on May 1, 2023: A map originally published within this story incorrectly identified the states of Mississippi and Louisiana. The map has been corrected.