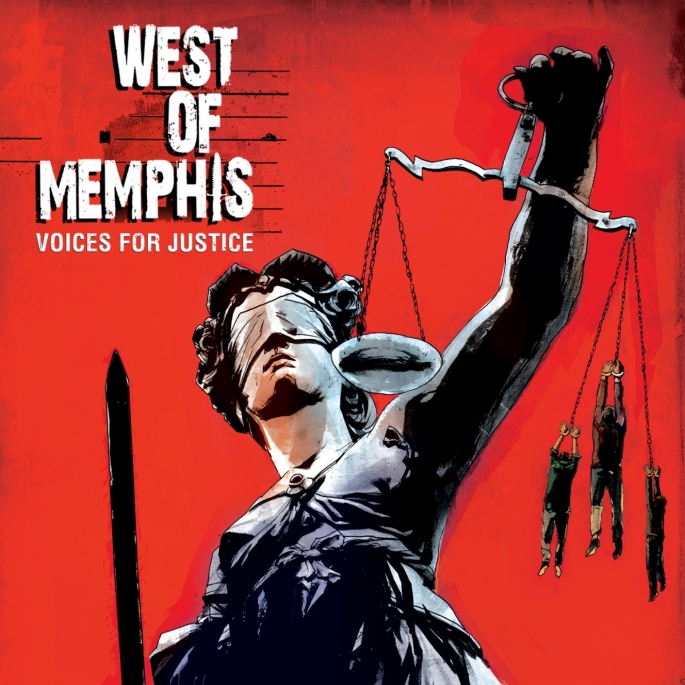

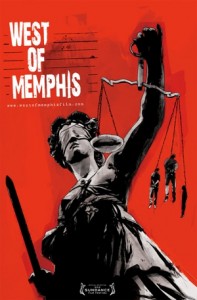

(Sony Pictures Classics, R)

Equality before the law is a basic principle of the American justice system. Faith in the jury system is another cornerstone of our system, and the wisdom of allowing local control in policing and justice matters is a third. All three come in for harsh criticism in West of Memphis, Amy Berg’s new documentary about the West Memphis Three, whose trial, conviction, and appeal has also been covered in the Paradise Lost trilogy of documentaries by Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky.

The West Memphis Three—Jessie Misskelley, Damien Echols, and Jason Baldwin—were teenagers in 1993 when they were charged with murdering three 8-year-old boys in West Memphis, Arkansas. This crime drew widespread publicity due to its horrifying nature: the bodies of the murdered children were discovered, naked and hogtied, in a local creek, and appeared to have been sexually mutilated. Suggestions that the murders had been conducted as part of a Satanic ritual added another sensational element to the case.

A breakthrough came about a month later with the confession of Misskelley, a 17-year-old with a 72 IQ, who also implicated Echols and Baldwin in the murders. Although substantial doubts were raised at the time concerning the validity of the evidence against them, all three were convicted in 1994—Echols was sentenced to death, Baldwin to life imprisonment, and Misskelley to life plus two 20-year sentences.

West of Memphis is concerned primarily with the appeals process that led to the release of Misskelley, Echols, and Baldwin in an Alford plea deal, which allowed each to enter a guilty plea while maintaining their innocence. The Alford plea also allows the state of Arkansas to consider their cases closed, a fact not lost on the original trial judge, David Burnett, now an Arkansas state senator, who repeatedly refused to grant new hearings in the case.

Although dollar figures are not discussed in West of Memphis, the lengthy appeals process that led to their release clearly cost a lot of money, and would never have happened without support from a number of celebrities, including Eddie Vedder, Natalie Maines, Johnny Depp and Peter Jackson, all of whom appear in this film. This is where the principle of “equality before the law” becomes “all the justice you can afford,” because as a rule, the services of the best forensics and legal experts don’t come cheap.

The case presented in West of Memphis is damning, most of all for a bungling local police department and ambitious local officials who wanted the case solved and chose to overlook obvious suspects (most child homicides are committed by family members) and mishandled crucial evidence.

In an echo of the case of the Central Park Five, also the subject of a recent documentary, Misskelley’s confession was obtained in irregular circumstances, after lengthy, leading questioning. The medical examiner made all kinds of confident declarations during the trial which later turned out to be, at best, highly questionable. The jury apparently ignored evidence providing the accused with alibis, and about the lack of forensic evidence tying them to the murders. But since juries don’t have to explain their reasoning, we’ll never really know how they came to their decision. The end result—three young people essentially removed from society for the rest of their lives.

Two other stories are intertwined with the main narrative of the appeals process. One is the maturation of Damien Echols and the time and effort invested in the appeals process by his wife, Lorri Davis (both are producers of West of Memphis, along with director Amy Berg, and Peter Jackson and Fran Walsh). It’s not clear why the film focuses so much on Echols, as opposed to Baldwin and Misskelley, but the result is that you may feel you are watching a film about the West Memphis One, rather than the West Memphis Three.

The other story builds a case that Terry Hobbs, stepfather of one of the murdered boys, is the real killer. Hobbs has a history of violence against women and children, was the last person seen with the murdered boys, is a DNA match (along with about 1.5% of the population) to a hair found at the crime scene and has no alibi for the time period in which the crimes are believed to have been committed. Yet ultimately, all West of Memphis can assert is that he was the type of person who could have committed such a crime, which is more or less the kind of reasoning that led to the conviction of the West Memphis Three in the first place.

There is new information in Berg’s film, and some of it is fascinating, but the film as a whole loses its way in a thicket of details. I did appreciate the demonstration of turtles tearing apart a pig carcass, lending support to the assertion that the mutilation of the victims’ bodies were not caused by a serrated knife but by the many turtles living in the creek where the bodies were thrown. This demonstration also points out something forensics experts already know—when wild animals attack a corpse, they go for the soft tissue first, and that includes the genitals, thus providing an obvious explanation for the state in which the victims’ bodies were found.

Despite its extended running time, (147 minutes), West of Memphis feels oddly incomplete and unsatisfying. It’s heartfelt and angry, but also ultimately disappointing, particularly since this case has already been treated at length both in print and on film. Who will want to see it? I can think of three categories likely viewers: West Memphis Three completists interested in everything related to the case, people who prefer conventional documentaries rather than the more artful approach taken by Berlinger and Sinofsky in their Paradise Lost trilogy, and people who are new to the case and are willing to do some reading to fill in the details left out or glossed over in this film.