This story produced by the Chicago Bureau.

The close of 2012 focused so narrowly on terrible events and startling numbers - the Newtown massacre, for example, or Chicago’s sharp rise in homicides - some major criminal justice developments were nearly squeezed out of the national conversation.

Take the statements made just over a week ago by Cook County Board President Toni Preckwinkle, who vowed to take on the tricky issue of the skewed racial picture in the county’s corrections and justice system, including within the juvenile justice system.

Speaking to a group of reporters, the news – including a statement that she will “work with the actors in the public safety arena” to lessen the overall corrections population and push alternatives to locking up non-violent offenders – the story got little more than a day’s play on the airwaves and in other media. Always outspoken, the board president served many years as an alderman fighting for various social justice causes, including race and drug issues (she at one point challenged the validity of any national “war on drugs”).

So in saying she would lasso the needed parties to lessen the numbers entering the corrections populations, and continuing the pitch to rid Cook of the juvenile system as currently set up, Preckwinkle made news. The numbers, so often repeated, were underscored in her talk: “The last time I checked,” she said, “68 percent of the people in our jail were African American - or double their proportion in the overall county population. Translated, she is attempting to answer a criminal justice and societal problem that has stymied policymakers, academics and law enforcement, among others, for decades.

And yet, like so much news at the turn of the year, it was swallowed by national news of tragedy, the fiscal crisis and President Barack Obama’s cabinet changes, and the play didn’t last long.

Also struggling to gain traction was a push by advocates, politicians and the courts to tip the balance of juvenile justice away from harsh punishment to rehabilitation. But to do so, Preckwinkle’s promise to fix local correction’s racial imbalance, weighted so heavily against blacks and Hispanics, would have to be addressed.

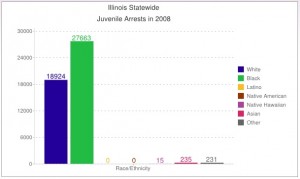

Graphic courtesy of The Burns Institute

In Shelby County, Tenn., the problem was so profound it recently invited a federal settlement to remedy it. Still, the problem of Disproportionate Minority Contact (DMC) continues to plague minority populations.

DMC, the racial tilt of the criminal justice system, is a long-running issue for many civil rights and advocacy organizations who have put out conflicting studies over the years that compete over the reasons, including low educational achievement and high unemployment among minorities, and urban environments with more open-air criminal conduct where the crime is more easily spotted by police (unlike in suburban and rural areas).

“For so long we’ve invested in building up these institutions (jails, juvenile courts, detention centers) at the detriment of investing in communities and social services, especially in the neighborhoods where [detained] folks are coming from,” said Tshaka Barrows, deputy director of the San Francisco-based Burns Institute, a national non-profit aiming, with law enforcement and community leaders, to erase racial disparity. “And that’s not a productive way of engaging your citizenry. We as a society really need to invest in education, housing infrastructure, etc., because that investment matters, as we see on the justice side.”

The trick is to speed the process and, perhaps, start to eradicate a stain on the system – one that has drawn an increasing volume of suits, legislation, and community pushes to inject balance in a system that too often spins out black and Hispanic minors who are further traumatized by prison, highly unemployable, and lacking a decent education to break the school-to-prison pipeline.

Cycle of Poverty, Incarceration Systemically Tied

Black youth make up 17 percent of the overall youth population in the United States, but they make up 30 percent of arrested juveniles and 62 percent of minors prosecuted in the adult criminal system, according to the D.C.-based Campaign for Youth Justice.

A look at Illinois shows black youth represent 85 percent of the juvenile justice population, according to the Cook County Circuit Court, even though they only represent one-fifth of the state’s youth population.

The problem was accelerated by the high-crime decades of the 1980s and 1990s that introduced severe laws targeting minors to stem a suspected “superpredator” generation that never came to pass. Youth prisons were built. Now they’re empty. Schools placed more and more police officers or guards in schools, something that is now on the map again following Newtown. Now there are studies claiming the presence of more security in the schools has only worsened the problem.

As it is, about 250 youth are locked up in the Juvenile Temporary Detention Center. Roughly 80

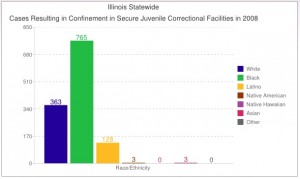

Graphic courtesy of The Burns Institute.

percent of that population is black - and year-to-year stats put the black population in juvenile dentition at roughly 75 percent of the total, which includes about 15 percent to 18 percent Hispanics and 7 percent white.

"Why,” asked the board president in Cook County, which covers Chicago, “is there a disproportionate number of black children in the JTDC and what does it say about the way we police our communities?"

Very often, police, called out to crime dens on Chicago’s South and West Sides, sweep streets or target large areas to clear them of crime and blunt the prospects of violent gang reprisals. In doing so, they snatch up a large percentage of black and Hispanic youth, who are most likely to be stuck in the cycle of poverty and poor education that so feeds the criminal justice system.

"It's not necessarily true," she said, "that the more people you arrest, the safer the community you have. And you're more likely to end up in secure juvenile detention if you are African American and display the same behaviors as someone of another race."

Balancing Justice

Since the mid-1970s, the U.S. Department of Justice has recognized the disparity, and taken measures to address it, be it for drugs or other felonies that could land youngsters in adult court. But it’s been a tough, often losing fight.

For example, take drug arrests of minors – a push to tackle a problem that quickly drove incarceration rates up dramatically. But recent studies show states’ recent decriminalization of some use of marijuana – including in California – has already resulted in a downward spiral in youth crime rates.

Already, pot bars are starting to grow up in that state, while others consider following its lead, and still others, including Illinois, are working on laws to ease restrictions on medical marijuana. Also, cops in Chicago have started focusing on greater stashes to justify arrests – meaning fewer people are arrested, and therefore jailed.

Indeed, in California, 2011 saw a 61 percent drop since 2010 of youth arrests for marijuana possession, according to a recent report by the Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice. The new state law reducing that offense from a misdemeanor to an infraction directly affects juvenile detention numbers, as drug arrests are the leading cause of youth confinement.

What remains to be seen is whether the racial and ethnic disparities of those arrests will also drop. Experts hesitate to be too optimistic considering the institutionalized disparities in America’s juvenile justice system. As with most crimes, minorities aren’t more prone to drug use or drug possession than whites. Nevertheless, minorities count for a disproportionate number of drug arrests.

In 2009, the rate for drug violation arrests for black juveniles was twice the white rate, according to the federal Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. Black youth are also much more likely (48 times more likely in 2001, and the numbers haven’t budged much since) than white youth to be incarcerated in an adult prison after a first-time drug arrest.

Laws such as California's are attempting to hit this issue from the policy level. But many of the ground-level factors contributing to DMC are not adequately addressed, according to experts in the field.

New York City police statistics show that between 2005 and 2010, police made 2.5 million stops. Of those, 90 percent were people of color and 90 percent did not result in legal action.

“The police are a critical part of the juvenile justice decision-making system and are afforded far more discretion than any other formal agent of social control, but researchers have paid surprisingly little attention to contacts between police and citizens, especially juveniles,” according to criminal justice professor Alex Piquero of the University of Maryland-College Park.

Piquero, in research dating to 2008, said police act as the “gatekeepers” to juvenile courts, and if their decisions are somehow race-based, minorities will continue to be overrepresented in the corrections system.

“The first step is to really address the use of data within jurisdictions … to look at [the numbers] regularly enough to help drive the way people make decisions,” Barrows said.

For example, jurisdictions look at how many kids in juvenile detention centers are from a particular geographic area. In Chicago, the concentration is on the heavily minority neighborhoods on the South and West Sides.

Other standards include the study of race, ethnicity, gender and offense. After assessing it, the idea is to monitor the data and reform the responses and thinking practices that have contributed to systematic disparity.

The Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention was created by – and is directed by – the Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act of 1974. Providing a federal grant program, it requires participant states to address DMC through a data-driven approach. This calls for states and communities to assess their DMC levels and develop mitigation initiatives.

However, many in the system, including experts, the affected minors, teachers and law enforcement, say the nearly 40-year-old law has little teeth. As a result, communities nationwide are using increasingly innovative measures to tackle DMC.

Recent models use community interveners or mentors to talk to kids directly, attempting to de-escalate a situation through an adult rather than automatically resorting to detention.

In the New York City neighborhoods of Harlem, Jamaica and South Bronx, the New York Department of Probation is collaborating with residents, businesses and organizations in what is called the Neighborhood Opportunity Network.

This model attempts to connect probation clients to community-based resources and services to avoid recidivism usually caused by ineffective, cyclical, punitive measures. Such initiatives are examples of what Barrows calls a “renaissance” of community engagement and partnership approaches in dealing with racial and ethnic disparities.

However, with today’s Congressional push for spending cuts – as well as ongoing budget deficits at the state level, especially in Illinois – juvenile justice funding has taken a back seat to other, more popular or welcome projects.

"Our big concern right now has to do with the cuts to juvenile justice funding, part of which gets used to make sure [states] comply with JJDPA,” said Benjamin Chambers, National Juvenile Justice Network spokesman. “Without those resources, they don’t have to comply. And that’s a slippery slope.”

Bureau editor Eric Ferkenhoff contributed to this report.