LOS ANGELES -- I have the privilege of serving as the current president of the National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges (NCJFCJ). Our organization is the nation’s oldest judicial membership organization with approximately 2,000 members nationwide, mostly judicial officers. NCJFCJ’s function is to provide education, technical assistance and research for our nation’s juvenile and family court judges and others working in our child welfare and juvenile justice systems. In addition, NCJFCJ often weighs in on, or is asked to weigh in on, important policy issues impacting children and families.

LOS ANGELES -- I have the privilege of serving as the current president of the National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges (NCJFCJ). Our organization is the nation’s oldest judicial membership organization with approximately 2,000 members nationwide, mostly judicial officers. NCJFCJ’s function is to provide education, technical assistance and research for our nation’s juvenile and family court judges and others working in our child welfare and juvenile justice systems. In addition, NCJFCJ often weighs in on, or is asked to weigh in on, important policy issues impacting children and families.

In January of this year, NCJFCJ was asked by representatives of Vice President Joe Biden to provide input to the committee he chaired that was tasked to make recommendations to President Barack Obama after the Newtown school shootings. Specifically, our organization was asked our views on increased school security in schools.

While we do not disagree that schools need to be safe for all of our children and school personnel, we wanted to remind the committee that the security issue needs to be approached with caution for a variety of reasons, not the least of which is its potential impact of the so-called school to prison pipeline.

We wrote that many counties across the country experienced significant increases in minor school arrests when police began to be placed on campus in the 1990s. School safety did not improve with increased police presence but graduation rates did fall.

In addition, there is research that shows that a first-time arrest doubles the odds that a student will drop out of high school, and a first time court appearance quadruples the odds. The American Psychological Association, the Council of State Governments and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have all found that this high level of discipline, including arrests, predict grade retention, school dropout rates and future involvement in the criminal and juvenile justice systems.

Ultimately, this negatively impacts young people when they apply to college, for a job or to join the military. Further, research suggests that the influx of police in schools has contributed to an overall environment that jeopardizes rather than enhances school safety. As a result of all this, there has been a growing national trend to reduce police involvement in schools.

In 2012, NCJFCJ passed a resolution entitled, “Juvenile Courts and Schools Partnering to Keep Kids in School and Out of Court,” which among other things noted, that zero tolerance policies have resulted in increased suspensions, expulsions, arrests and referrals to the juvenile justice system while the overall rate of school violence has remained stable or has declined. As an alternative to zero tolerance policies and additional police in schools, NCJFCJ supports the following:

-School administration discretion in handling school misbehavior;

-Testing and implementation of alternatives to zero tolerance policies such as systemic school-wide violence prevention programs, social skills curricula, family engagement and positive behavioral supports;

-Collaboration of the juvenile justice system, schools and community agencies to foster positive relationships with students to promote school attendance and academic success;

-Judicially led collaborations to reduce school exclusions with intensive training, technical assistance and public education.

In July 2012, with foundations’ support, NCJFCJ began a new project entitled “Judicially Led Responses to Eliminate School Pathways to the Juvenile Justice System.” Its goal is to support and implement our earlier resolution.

There are good examples of judicially led collaborations in this arena. Most notably, Judge Steven Teske of Clayton County, Ga., brought together the court, law enforcement, schools and others to develop alternatives to law enforcement referrals which had sky-rocketed in his county.

The result was a 70 percent drop in school referrals to juvenile court between 2003 and 2010. Serious weapons incidents on campus dropped nearly 80 percent. Most importantly, graduation rates increased by 20 percent while felony rates decreased by 51 percent. Other jurisdictions have followed this approach with success.

Here in Los Angeles, where I preside, we created a School Attendance Task Force to develop ways to encourage young people to attend school rather than punish them for not attending. Our efforts helped bring about changes in law enforcement practices, school policies and even caused the Los Angeles City Council to revise its daytime loitering ordinance to conform to a more positive approach implemented by our courts which were handling 10,000 to 20,000 citations for daytime loitering each year.

In doing so, we heard from schools, students, community activists and others. There has been a decrease in the number of these citations and most importantly from my perspective, a feeling by many members of our community that their voices can and will be heard by public officials who work for them.

Our local task force also passed a resolution calling for development and implementation of many of the notions espoused by NCJFCJ and put into practice by Judge Teske and others. The point here is that, instead of over utilizing our courts and law enforcement agencies in typically punitive ways, judges, working with law enforcement, schools, agencies, families and communities can help make our schools and communities safer, healthier and more productive by taking more positive approaches with our youth and their families.

It’s hard work, but it works.

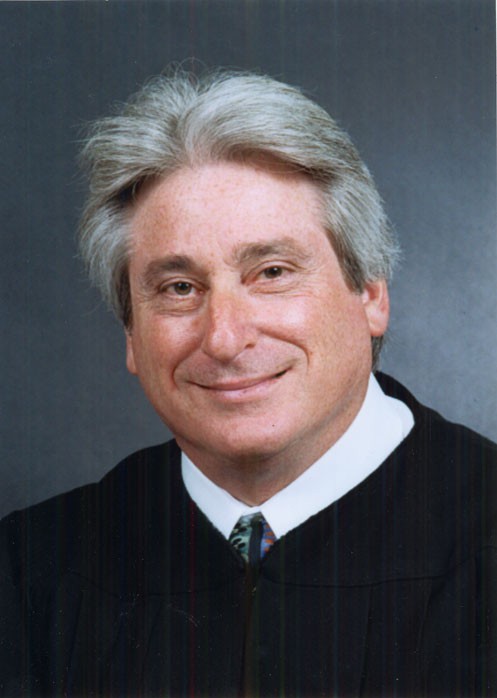

Michael Nash is the Los Angeles County, California, Juvenile Court's presiding judge and the president of the National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges.