When a young man convicted of an adult offense began to act out in the custody of the Oregon Youth Authority, he wasn’t sent to an adult facility, as was often done in the past. Instead, case managers looked at his history — a data-rich map of his background, behavior and contact with the juvenile justice system. His profile also included family information and personal behaviors with drugs and alcohol.

The agency decided that based on his individual record, he would have been best served staying within the juvenile justice system and, with his input, enrolled him in a vocational program.

“He turned into one our best young men,” said Ann Snyder, spokeswoman at the Oregon Youth Authority. “We wouldn’t have been able to give him the options — we used the data about him.”

Oregon has been seen as a leader among juvenile justice workers for collecting comprehensive data on recidivism and positive youth outcomes, and for using that data to shape policies. The information collected has been used to better understand a youth’s risk of reoffending and what type of treatment programs would work best for an individual, Snyder said.

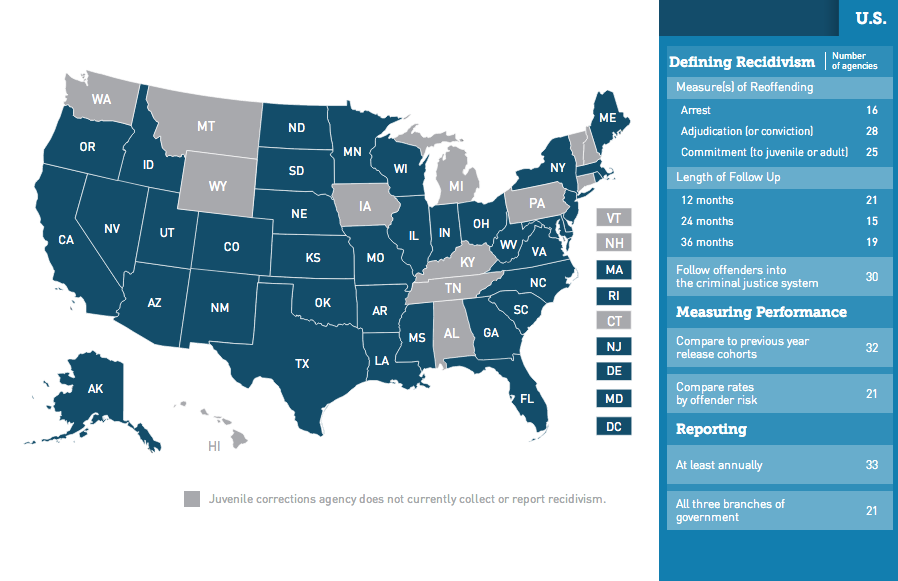

But not all states are following suit in tracking such data. A quarter of state-level agencies across the country do not currently collect or report recidivism data, according to a recent survey conducted by the Pew Charitable Trusts, the Council of Juvenile Correctional Administrators and the Council of State Governments.

The rate of recidivism is often used as a basic measure of success of a criminal or juvenile justice agency.

The survey, which went out to 50 states and Washington, D.C., found that 33 juvenile corrections agencies reported recidivism data on a regular basis, five reported infrequently and 13 did not report or collect this type of data at all at the state level.

“You get what you measure. If you’re not measuring something or if you’re unable to measure it, you don't know if your policies, programs and practices are having the intended impact,” said Adam Gelb, director of the Public Safety Performance Project at the Pew Charitable Trusts.

The survey also found that most juvenile justice agencies used several definitions of recidivism. While some states measured recidivism when a young person was re-arrested, others measured it when a young person was convicted or adjudicated.

“We found out that states were measuring it differently, therefore, you couldn’t compare state-to-state,” said Ned Loughran, executive director of the Council of Juvenile Correctional Administrators.

In addition, while some states, like Virginia and Florida, measured re-offense rates of youth as early as six months from the date of release, other states only measured 36 months out of leaving custody.

Loughran said the fact that some states don’t measure recidivism rates on a state level surprised him. He said the Council of Juvenile Correctional Administrators has worked hard with its members to collect such information, and issued a white paper several years ago.

But for states that weren’t collecting or reporting recidivism data, it doesn’t necessarily indicate that the data isn’t being collected at all, said Gelb of the Pew Charitable Trusts.

“Just because they’re not reporting recidivism data on a regular basis doesn’t mean there’s a lack of recidivism reduction as a goal,” said Gelb, of the Pew Charitable Trusts. “It may mean that the data isn’t adequate.”

The survey found that technical issues were some of the difficulties states faced in collecting data, said Josh Weber, program director for juvenile justice at the Council of State Governments.

“States talked about the difficulties of pulling together accurate and comprehensive data across the various locales that make up their juvenile justice system,” Weber said.

Juvenile justice systems across the country are very different from one another, he said. While one single agency collects the data in some states, in others, like Wyoming, different counties house the data on juvenile inmates.

“There’s a lot of different pockets where this information lies and there’s really nothing comprehensive that brings that all together right now,” said Rachel Campbell, social services program analyst at the Wyoming Department of Family Services.

She said the state has made it a goal to organize the data, and says the Wyoming legislature allocated money this past session to work towards a more comprehensive case management system.

Weber said that states that have been collecting data more accurately have a shared a single electronic system, like in Oregon, where a single system pulls in data from the state’s 36 counties.

In Alabama, the Department of Youth Services doesn’t have access to the data from the courts, said David Rogers, deputy director for administration at the Alabama Department of Youth Services. He said he wasn’t aware of any efforts to collect that data at this time.

In Tennessee, the survey noted that as of January, the agency began to define recidivism as re-commitment to a facility within two years of release and will begin reporting and sharing the data at least annually.

But Loughran, of the Council of Juvenile Correctional Administrators, says that more needs to be measured eventually. He said that recidivism is a fundamental measure of success in juvenile justice systems, but doesn’t give the full, robust picture.

“The next logical step is to measure positive youth outcomes,” he said, which include the completion of education, employment and social connectedness.

Pingback: Columna de Opinión (Inglés): Juvenile Recidivism Measurement Inconsistent Across States within USA | NotiProyecto B