Kayleigh Skinner

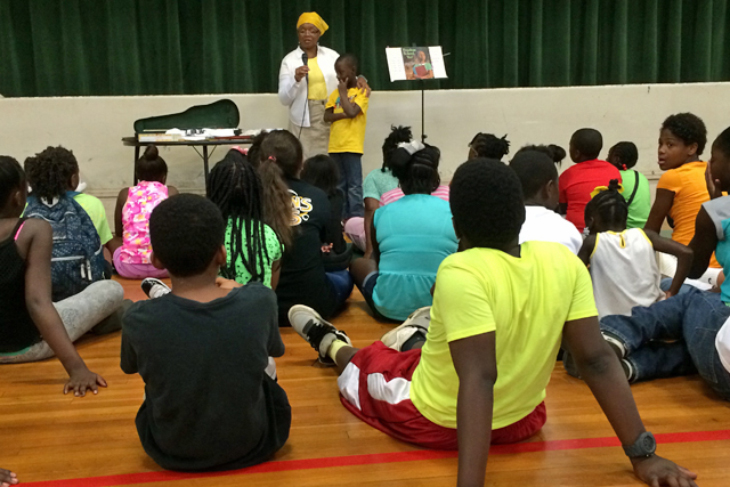

Lynn Gilmore reads to Freedom School students in McComb.

From The Hechinger Report:

McCOMB, Miss. — When Alana Johnson starts fifth grade at Higgins Middle School on Monday, she may have a leg-up on 10-year-olds who had the summer off.

That’s because she spent her days in a modern-day version of Freedom School, an academic enrichment program originally created in the civil rights era to teach history and literacy with the goal of empowering African-Americans.

And it was all her idea, according to her mother, Kosheya Johnson.

“I wasn’t even going to enroll her this year, but she loved it so much last year that she asked me about it and she was adamant,” Johnson said.

Alana is one of 60 students who attended McComb Freedom School housed at Higgins, a six-week program aimed at fighting the so-called summer slide, when students forget what they’ve learned during the school year.

At a time when Mississippi’s test scores lag behind national standards, Freedom Schools have been making a comeback. They owe their revival to the Children’s Defense Fund, a non-profit advocacy organization that runs Freedom Schools in 29 states, including two in Mississippi.

The goal is help students learn to love reading.

Students who stop reading during their summer break are likely to lose ground on literacy skills and come back at a disadvantage in the fall, said Katie Willse, chief program officer at the National Summer Learning Association in Baltimore, Md.

“Athletes, teachers, artists, these folks are constantly practicing their craft and working on their skills,” Willse said. “We think about summer learning in the same way.”

The fight to improve Mississippi’s schools has its roots in the Freedom Summer of 1964, when Freedom Schools first got started, held “in church basements, on back porches, in parks and even under trees,’’ Children’s Defense Fund President Marian Wright Edelman recently wrote.

Fifty years later, the classroom-based Freedom School that Alana attended in McComb retained the original mission of educating disadvantaged youth, without the influx of northerners, which the earlier movement attracted.

Alana is not a struggling student, but many of her classmates are. In Mississippi, some 79 percent of fourth graders in the state could not read at grade level in 2013, compared to 66 percent nationally.

Scores did not improve with older students; last year, a little more than half of eighth graders scored proficient or advanced on the state’s language arts exam.

Freedom Schools remain a potential solution to improving literacy in a state where reading scores have long stagnated.

“Black children and children of color, poor children are still not getting an equal education,” said Patti Hassler, vice-president of communications and outreach for the Children’s Defense Fund. “The poor schools do not have the resources that the wealthier school districts have.’’

Education advocates are pushing for change, noting that spending on public education consistently fails to meet the needs of students. In the past six years alone, Mississippi has underfunded schoolsby more than $1 billion, leaving many without adequate supplies, books or adequate buildings.

The Better Schools, Better Jobs ballot initiative is attempting to amend the Mississippi constitution by gathering more than 107,000 signatures and putting the issue before voters in November 2015.

The original freedom schools served largely African-American students, but now include a variety of races. The majority of McComb students in Alana’s classes were black, but Hassler said demographics vary based on location.

Higgins received a federal literacy grant to cover the costs of the McComb school. It costs about $59,000 to run a summer Freedom School, funded via grants and donations so that students aren’t charged. They receive no money from the Mississippi Department of Education, said Patrice Guilfoyle, its communications director.

Dancing, reading, singing

Alana’s Freedom School, started the day in the gymnasium with a ceremony called “Harambee” — Swahili for “coming together.” Both the student “scholars,” as they are known, and “servant leaders” gathered in a circle to sing about empowerment and self-confidence.

Alana and her peers attended colorfully decorated classrooms with just 10 students. One room had a “Welcome to Africa,” theme, decorated like a jungle. Another had an actual camping tent where students could read.

Kayleigh Skinner

Site coordinator Donovan Hill gathers the Freedom School students to start the Harambee.

In addition to reading help, the school provided lessons in black history at a time when many Mississippi youth are unaware of their state’s dark past and violent battles over civil rights.

Students spent their final week preparing for the “finale,” a series of historical skits. They did all their own research.

Friends and parents watched the students recite famous quotes by Nelson Mandela and act out news stories, including the Rodney King beating and the shooting of Trayvon Martin in 2012.

Alana and her classmates told the audience what happened to the “Little Rock Nine,” — black students who integrated Little Rock Central high school in Arkansas in 1957.

Past and present

Today’s Freedom Schools are taught by local college students. In McComb, the six servant leaders at Higgins all graduated from district schools. They were trained in Clinton, Tenn. by the Children’s Defense Fund, where they learned to guide students through the program’s designated reading curriculum with its “I can make a difference” theme.

“College kids were the ones that galvanized that whole movement,” said Lakya Washington, assistant principal at Higgins and director of its Freedom School. “These guys need to be here because they make the difference.”

McComb site coordinator Donovan Hill, a recent graduate of Alcorn State University, said the training changed his life. He’s now a city councilman in McComb and mentors students throughout the year.

“It’s just this atmosphere of motivation,” Hill said. “I was ready to drop out of college and I went to Freedom School training and realized no, I can’t do that.”

In McComb, the central theme is evident on posters that adorn the walls. Each notes a different place where students, can make a difference, “myself,” “my community,” “the world.”

Washington said the students “get some very good reading instruction daily, for six-weeks.”

Children Defense Fund’s Patti Hassler said the numbers showed that the students successfully averted the summer slide. Evaluations from a Freedom School program in Charlotte, N.C. show that 90 percent of students suffered no summer learning loss; about two-thirds showed reading gains.

Eric Powell, 10, who is entering fifth grade at Higgins, boosted his reading scores after his first year at Freedom School, according to his mother, Alfonda Renee Westbrook. And that’s not all.

“The thing that is very interesting to me is learning history,” Eric said. “They teach me about my culture.”

There are other free summer programs in McComb, but only the Freedom School ran every weekday for six-weeks, and was not taught by district staff.

It was one reason why Alana wanted to go: she had so much fun it didn’t seem like school.

“They make it exciting for them,” said Johnson, Alana’s mother. “The funny part is they don’t even realize they’re learning.”

Alana doesn’t expect regular school to be as much fun, but she still looks forward to starting. She said she is excited “to go see my friends and learn and stuff,’’ although there is something she dreads: “The time that I have to wake up.”

This story originally appeared in The Hechinger Report.