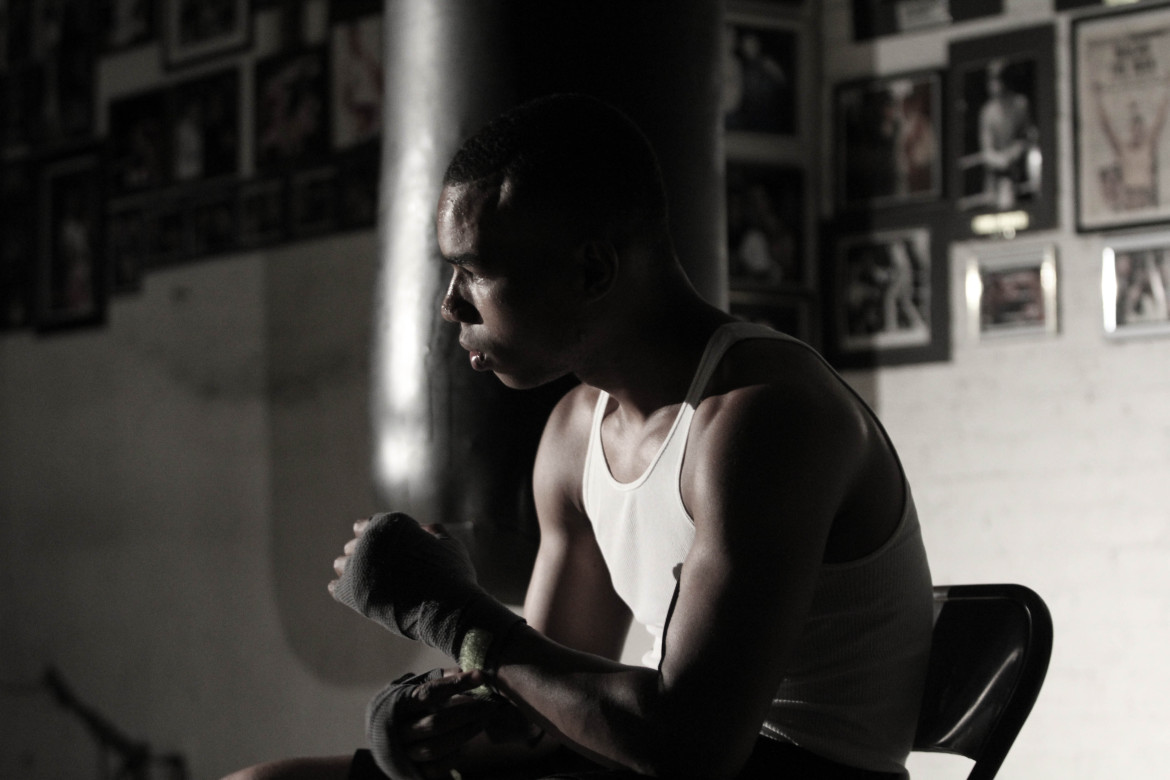

On a recent Saturday afternoon as Jalil Regalas stood outside in front of Morris Park Boxing Club in the East Bronx, the diamond-studded golden glove pendant that hung from his neck seemed to attract strangers like a magnet.

“What’s up, champ,” an older man said, reaching out for a quick handshake and congratulating Regalas as he walked by.

Back in April, thousands of boxing fanatics, friends and families of amateur fighters packed the Barclays Center in Brooklyn for the finale of a nearly three-month long tournament. It was the day the 20-year-old says he’ll cherish for a lifetime. It was a day of physical and mental exhaustion, but a day of triumph, and the day when he would become a first-time Golden Gloves champion.

“I used to go into jewelry stores around Christmas time to look at chains, and I would say ‘I want that’, but then I would say ‘nah, I’m not going to get it.’ I wanted the Golden Gloves to be my first chain,” he said.

The famed Morris Park Boxing Club has been Regalas’s training home for the past two years, but it wasn’t the first place he’d put on a pair of bulky Everlast boxing gloves. A delinquent childhood of robbery landed him in court a few months after he completed the eighth grade. Regalas, who was 15 when he got arrested, went to a non-secure detention center in upstate New York where he was introduced to the sport.

“Before I got sentenced my lawyer asked me what I wanted to be and I told her a boxer. They sent me to a non-secure facility because they had a boxing program there.”

A number of juvenile correctional facilities across the country are using organized sport to reduce juvenile recidivism. But, overlooked at times is the life-changing role sports can have on at-risk youth, “especially for young men,” said Dr. Laura Abrams, a social welfare professor at the University of California, Los Angeles.

“We put too much focus into therapeutic programs in these facilities and forget that these are things kids need,” Abrams added.

Sports in detention centers have been shown to reinforce positive values in behavior that can lead to a sense of belonging and self-control. Boxing, however, isn’t common in detention centers, according to some experts, and can do more harm than good for youth with violent pasts.

“Programs have to make decisions on what they think will benefit the majority,” Abrams said. “But, I don’t think boxing would be the appropriate choice for young people with a history of aggression and crime.”

For Regalas, that wasn’t the case.

“The program gave me confirmation that this was something that I was really good at and could keep doing once I got out,” he said. “And, I told myself that I wouldn’t mind my job to be exercising.”

In anticipation for fighting professionally, Regalas started training with former WBA light heavyweight champion Lou Del Valle, who also began his career at Morris Park gym. Del Valle replaced his once scrappy street fighting style with disciplined ring craft.

Del Valle trains 16 fighters — both men and women — but says Regalas’s “throwback” fighting style makes him a unique student of the sweet science.

“Fighters today just hit, run and hold. Jalil is going to stand there and bring it to you,” said Del Valle. “I see him more confident every day and that’s what makes me think he is going to be even greater than I was.”

Training with Del Valle “has been intense,” Regalas said. “He sees my potential so that’s why he pushes me so hard.”

Ever since the Golden Gloves ringside bell first rang in a Chicago stadium in 1923, the series of amateur bouts has been a stepping-stone for fighters and propelled boxing careers for legends like Muhammad Ali. The annual New York Daily News Golden Gloves, is a “mini Olympics” of sorts, and the prime arena for young boxers of the Empire state to showcase their talent and inch closer to the pros.

Once a promising amateur boxer with plans to compete in the tournament, Dewey Bozella said boxing became his salvation during the 26 years he spent behind bars. Bozella’s dream to go pro was shattered following a 20 years to life sentence for a murder he didn’t commit.

After a few years at Sing Sing maximum-security prison, Bozella decided to enter the prison-boxing program where he became the undefeated light heavyweight champion. Hours spent in the gym daily gave him the strength he needed to earn two college degrees and to continue fighting for his freedom.

“Boxing saved my life. I knew how to deal with people much better because I was able to put my anger, pain and frustration somewhere else,” Bozella said in a phone interview.

The closest shot Bozella got at a professional bout while in prison is when he went toe-to-toe with Lou “Honey Boy” Del Valle.

“He was one of my toughest fights,” said Del Valle, who was still an amateur when the fight was arranged by a prison guard who ran the program. “It was two guys that were hungry to prove something. He was locked up and wanted to prove his innocence and I was on a mission to be a great fighter.”

“It was a great learning experience because Del Valle made me see my potential. That fight showed me I was capable of beating him and anybody else that stepped in front of me,” Bozella said.

That included fighting relentlessly to get out of a place he didn’t belong.

Sing Sing’s boxing program ended not too long after Bozella was exonerated in 2009 with the help of The Innocence Project, an organization that uses DNA to overturn wrongful convictions.

Bozella said he is now living his dream by conditioning young bodies and minds through a sport that he believes “teaches morals, obligations, responsibility, and discipline.” This past summer The Dewey Bozella Foundation started CHAMPS camp in Newburgh, N.Y., to help at-risk youth, like Regalas avoid the pitfalls of the streets.

“If it wasn’t for boxing, I probably would have gone back to doing what I was doing.” Regalas said. “I found something that has me working hard everyday to be great.”