Christina Clarke, the head of continuing medical education at Wake Forest University School of Medicine in North Carolina.  Brian Bride, the head of the School of Social Work at Georgia State University. |

Maybe it starts as an extra drink after work — you know, just to take the edge off. Or an extended gripe session at lunch.

But maybe it stretches out into a long silence after dinner. An explosive snarl at a minor snag. The odd nightmare. And maybe — just maybe — it starts coming into the office as a vague sense of dread or pointlessness, a late start here and there, an urge to dodge co-workers or clients.

For workers in fields like juvenile justice and youth welfare, gazing into the abyss of someone else’s trauma every day can start taking a bite out of their own psyche. It’s called “compassion fatigue,” and it’s increasingly being recognized as a hazard in the social services workplace.

Christina Clarke, the head of continuing medical education at Wake Forest University School of Medicine in North Carolina, called it “the cost of caring for others in emotional and physical pain.”

“Can we walk through water without getting wet?” Clarke asked. At some point, the immersion in someone else’s hurt starts to take a toll — and no one is completely immune.

“It attacks the very core of what brought us into this work — our empathy and compassion for others,” Clarke said. Left unaddressed, it can lead to cynicism, damaged relationships, depression and stress-related illnesses, she said.

Clarke spoke at a recent seminar on the issue put on by the federal Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. Another presenter, ToriShana “TJ” Johnson, said working with troubled children and teens “weighs heavy on your heart, and it can affect your ability to deal with stress if you don’t have the appropriate resources.”

“We must learn to unplug from work, and this is very difficult for the individuals who are very dedicated to the work that they do,” Johnson said.

Researchers began to identify the problem as an offshoot of studies into post-traumatic stress among Vietnam veterans, said Brian Bride, who has studied compassion fatigue since the early 1990s. It’s relatively common and fuels high turnover rates in social service agencies, he said.

Researchers began to identify the problem as an offshoot of studies into post-traumatic stress among Vietnam veterans, said Brian Bride, who has studied compassion fatigue since the early 1990s. It’s relatively common and fuels high turnover rates in social service agencies, he said.

“With social workers, probably 10 to 15 percent at any given time have relatively severe compassion fatigue,” said Bride, the head of the School of Social Work at Georgia State University. “I’ve looked at sex abuse counselors, that’s at 20 percent. Among the highest are child protective service workers who work with [victims of] sexual assault, physical assaults, and that’s about 33 percent.”

Others show symptoms similar to post-traumatic stress, depression and anxiety, said Bride, who developed a 17-question survey to measure those impacts in the late 1990s.

There’s a high correlation between compassion fatigue and ordinary job burnout, but burnout is more of an organization issue.

“Burnout seems to be a reflection of tension between resources and the amount of work that needs to be done, and then working with difficult populations contributes to that,” Bride said. “Whereas with compassion fatigue, the real causative factor is hearing the stories of trauma.”

Excessive venting can make things worse, Johnson said. It’s not unhealthy to discuss a problem with coworkers — but once the problem is aired, the talk should turn to solutions.

“What you’re doing is reliving that incident, reliving those same issues,” she said. “And then your emotions are actually intensified and heightened, and you’re back to where you were, if not worse than when you first started discussing the situation.”

So a certain degree of compassion fatigue may be inevitable. However, researchers have identified a variety of ways to beat back its advance.

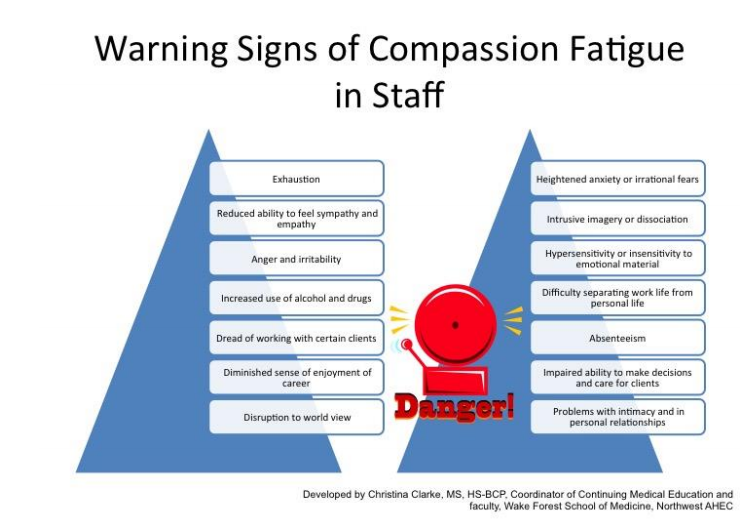

- Be aware of the symptoms. They can range from physical ailments like headaches and upset stomachs to insomnia, irritability and excessive drinking or smoking. Those can not only hurt performance, but can endanger safety, Clarke said.

- Seek support. People in the same field are likely to have faced similar problems and may have helpful advice, Johnson said. Ask about employee assistance programs. Family can help; and don’t hesitate to see a counselor or therapist.

- Practice self-care. Make sure you’re maintaining boundaries between your professional and personal life, Clarke said. Diet, exercise and hobbies can help take your mind off the stress; so can a spiritual component.

- And finally, take a break. Working harder under stress “doesn’t make it easier to cope with,” Clarke said; “In fact, it worsens the situation.”

“Whatever you choose to do — whether it’s prayer, meditation, being one with nature — something that gives you a sense of peace is important to your mental capability and your mental and emotional stability,” Johnson said.

And volunteering in the community can help, but avoid causes similar to your job: “You don’t want to actually contribute to compassion fatigue because of the type of volunteer activity you decide to participate in,” Clarke said.

Don’t just take 10 outside, take a “mental health day” once in a while, or take your vacation time.

“We need to be able to listen to our bodies, understand it’s OK to take a breather,” Johnson added. “When we continue to ignore warning signs, the mental and physical effect of compassion fatigue can be very detrimental to our health.”

This article was originally posted on Youth Today.