On the Saturday morning marking the 6th anniversary of her son's death by gunshot, Savannah City Councilwoman Linda Wilder Bryan said her prayers, then drove her Land Rover SUV, with its boxes of school supplies, tablecloths, hygiene sundries and children's bicycles, to a recreation center hosting her "Celebration of Life Event."

An homage to her dead son, it involved giving her load of things to kids whose parents can't afford to buy them.

"We need some hands,'' she said, forcefully, to a man who wasn't a volunteer or otherwise associated with the event. Without Wilder Bryan’s permission, he appeared to be inspecting the tables of giveaways she was assembling.

Wilder Bryan kept it moving like that. She directed volunteers, paused for interviews with local TV reporters, posed for photographs with other politicians and the police chief.

But when one of those reporters asked how she copes, her eyes welled up. Her head dropped.

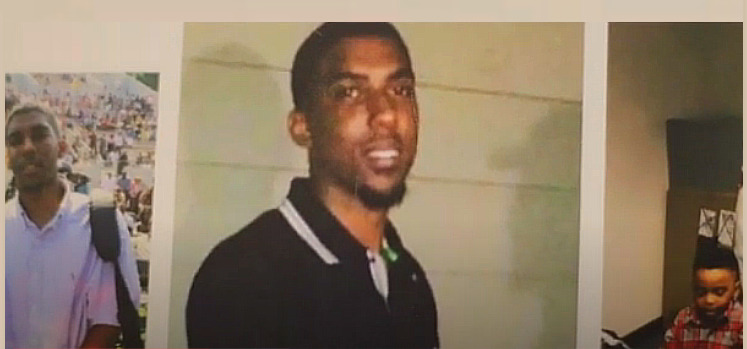

William Martin (video screenshot)

City Councilwoman Linda Wilder Bryan

With her morning prayer, she’d memorialized her son Lawrence Bryan IV, who was 23 when he died, other lives lost to gun violence and the people who will never stop loving or grieving them. That was the answer she gave once she held up her head again.

Wilder Bryan’s community endeavors, inspired by her son’s murder, are a response to trauma and a sign of human resilience, said Catherine Gayle, chair of Savannah State University’s social work department.

It’s not uncommon, she added, for those traumatized by gun violence to project what outsiders might view as a kind of superwoman or superman persona — one that can melt away at any given moment — whose complexities may not be fully understood.

Researcher: More research should focus on those left behind after a gun death

Though there’s been considerable research about the well-being of victims who survived being shot, relatively few researchers have focused on the mental, behavioral and other health impacts on persons who lost a beloved one to gun violence, said psychologist Shereefah Al Uqdah of Howard University.

Courtesy Shereefah Al Uqdah (Facebook)

Shereefah Al Uqdah, Ph.D.

Al Uqdah, who has a private counseling practice, said she’s seen what happens amid such great loss. And she has some anecdotes to share. But she is dismayed that those who fund scientific research largely have not seen fit to examine the toll on families devastated by gun-violence deaths.

"What is the culmination of all of their trauma?'' Al Uqdah said. "... How are we engaging in mental health and activism, especially if the reason that we're entering activism is that we've experienced the trauma? How are we helping ensure that the mental health of these individuals, who have now sparked the arm of social justice, is well … ?”

On her best, busiest days of raising awareness about gun violence, Wilder Bryan manages to confer with other Savannah City Council members. She addresses civic groups. She strategizes with police and other law enforcement officials on the scourge of gun violence.

On other days, Wilder Bryan grieves publicly, writing her terrors on Facebook: “I couldn’t sleep last night. Something was tugging at my heart. …and then it hit me as it gets closer to Aug. 7th.

Courtesy Linda Wilder Bryan

Lawrence Bryan IV, as a young man and a toddler, shot to death in 2015.

I get all hyped up, my stomach gets all nervous and queazy … It’s a night We will never EVER forget it’s when our ‘Boy Wonderful’ was slaughtered on the streets by a coward from the pits of HELL.”

That’s what overflowed on July 29.

As quoted in “Invisible Wounds: Gun Violence and Community Trauma Among Black Americans,” a May 2021 report published by Everytown For Gun Safety, Oji Eggleston, executive director of Chicago Survivors, said, “The physical and emotional wounds of gun violence often stay with survivors throughout their lifetime. Ongoing services that are tailored to the long-term experiences of gun violence survivors in the months, years, and decades following gun violence are essential to the support process.”

Pingback: Researcher: Trauma and grief-fueled resilience among those who lose someone to gun ... - Land Rover News