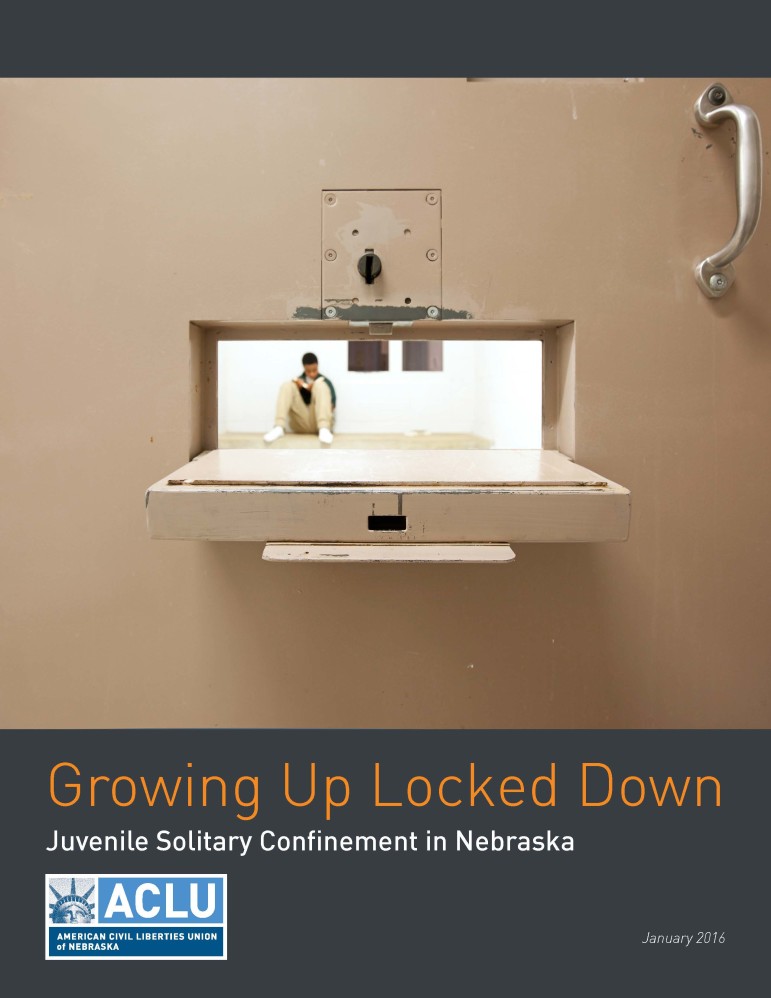

The solitary confinement policies for youth vary widely in Nebraska, with stays of weeks and even months permitted in some facilities, says a new report from the ACLU of Nebraska.

The solitary confinement policies for youth vary widely in Nebraska, with stays of weeks and even months permitted in some facilities, says a new report from the ACLU of Nebraska.

In the state’s nine facilities that house juveniles, the maximum stay in solitary ranges from five days to 90 days, some of the most stringent policies in the country, said the report, “Growing Up Locked Down.”

A youth can land in solitary for a serious rule violation but also for minor infractions, such as having too many books. The report is based on public records requests.

The ACLU also found several facilities lack a written policy on solitary confinement or logs that show the amount of time juveniles spend in insolation.

The group recommended lawmakers adopt a statewide policy on the use of solitary and consider banning the practice. They also recommended limitations and protections such as an appeals process, strict approval requirements for solitary stays of more than four hours and clear documentation about when and why solitary is used.

“This research makes clear that the policies and usage for solitary confinement among vulnerable Nebraskans truly shocks the conscience. We can and must do better,” said Danielle Conrad, executive director of the group, in a statement.

“This research makes clear that the policies and usage for solitary confinement among vulnerable Nebraskans truly shocks the conscience. We can and must do better,” said Danielle Conrad, executive director of the group, in a statement.

The report is one more example of growing concern about the use of solitary for youth and interest in eliminating it as a punishment. Researchers have found the practice can cause psychological and physical harm, especially among children and adolescents who are still developing.

In Nebraska, the average stay in solitary ranged from 1.76 hours to more than eight days during an 18-month period ending in June 2015, the ACLU found. The longest stay, of 90 days, came at the Nebraska Correctional Youth Facility, a state-run facility.

Dawn-Renee Smith, acting communications director of the Nebraska Department of Correctional Services, said the state is working with groups including the ACLU to develop regulations regarding the use of restrictive housing.

[Related: NY Activists Urge End to Solitary Confinement in Corrections]

“NDCS uses restrictive housing as necessary for youthful offenders adjudicated as adults and sentenced to its custody. There are processes in place to ensure a review by the facility warden as well as to provide the individual with a voice to appeal the decision,” she said in a statement.

Amy Miller, legal director at the ACLU of Nebraska, said the “jaw-dropping” policies and personal stories described in the report have provoked a strong reaction. People are sharing stories of their own experiences with juvenile solitary or those of their families in comments on social media. Even advocates and lawyers in the juvenile justice field have been surprised by the findings, she said.

“I think there’s a great amount of shock and surprise. That means it feel like there could be an opportunity for consensus,” she said.

The state’s legislative session began this week, and Miller is hopeful legislation may be introduced to reform solitary practices. A state law would be preferable to reforms at each facility, to ensure youth are treated the same no matter where they are incarcerated, she said.

Mark Soler, executive director at the Center for Children’s Law and Policy, said he expects to see more state action across the country this year to curb the use of solitary confinement for youth. The group is working with other organizations, including in the corrections field, to help build a national strategy around the issue.

More reports like the one from Nebraska are likely, and can provide the foundation for effective reform, Soler said.

“We need to know what the policies are in these agencies, and we need solid data on how those policies are implemented,” he said.

More related articles:

New Jersey Laws Could Pave Way for More Reforms

Most States Still House Some Youth in Adult Prisons, Report Says

OP-ED: California Bill Can End Solitary Confinement for Youth