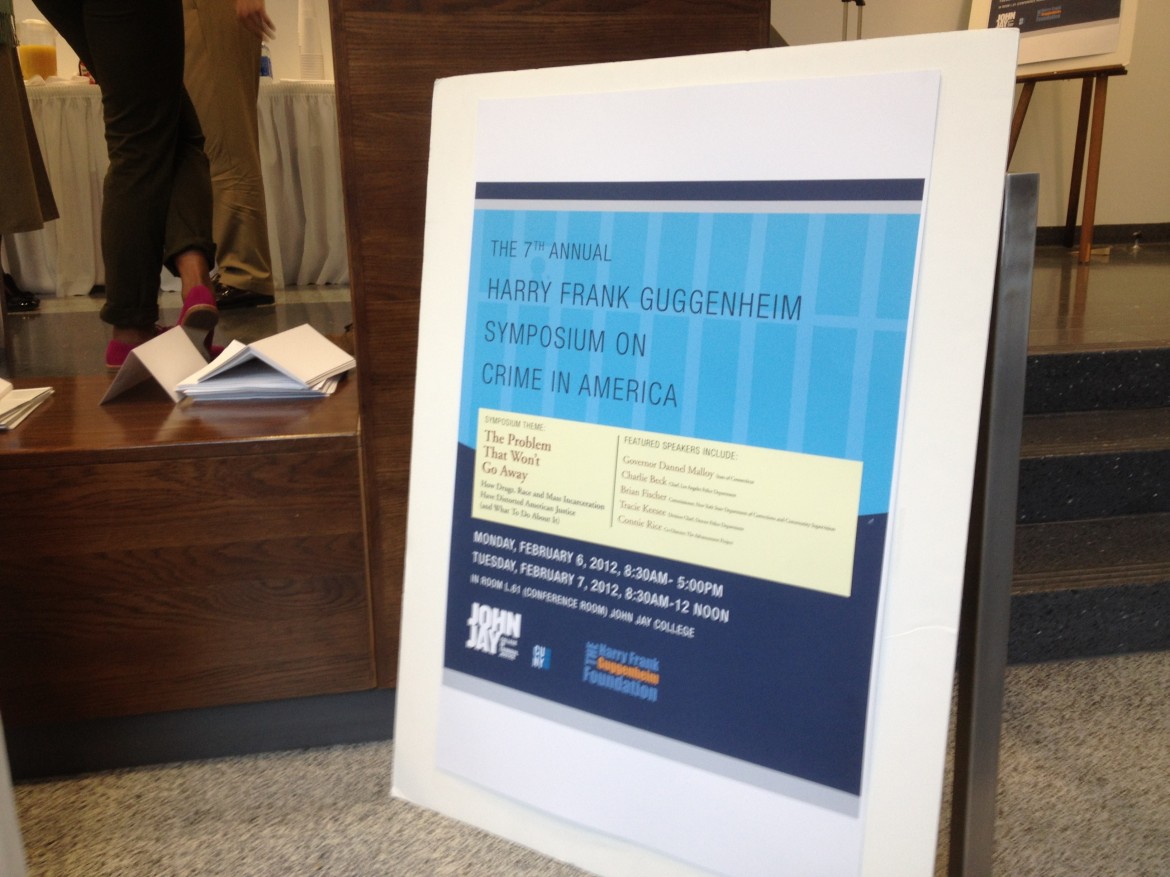

NEW YORK – Community was the word on everyone’s lips at the Symposium on Crime in America at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice. More police engagement with the community is needed to win the war against gangs, and communities need to be more receptive to those returning from prison, according to experts speaking at the conference.

NEW YORK – Community was the word on everyone’s lips at the Symposium on Crime in America at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice. More police engagement with the community is needed to win the war against gangs, and communities need to be more receptive to those returning from prison, according to experts speaking at the conference.

According to FBI data provided by Jeffrey Butts, Director of the John Jay Center on Research and Evaluation, violent crime arrests are at a 30-year low.

But "as violence has dropped," Butts said, "arrests for other crimes increased since the 1990s."

One reason may be that gangs are still a serious problem across the country and according to Los Angeles Police Chief Charlie Beck, gang violence has changed.

“It’s no longer about drugs,” said Beck. Today’s gang violence is territorial, he said, noting that only a small percentage of the 160 gang-related murders in 2011 had to do with drugs. He did say, however, that gangs are spreading out from Los Angeles.

“If you have Bloods and Crips [two prominent LA gangs] in your neighborhood, they came from LA,” he said.

Beck talked about a fundamental shift in how the LAPD approached the issue of gangs. He says police strategies of the last 30 years have been ineffective at curbing the spread of violence and fixing the root problems and what is needed is a better relationship between police and the community.

His wake-up call, he said, came the day he arrested the son of someone he had arrested years before.

As a response, Beck placed 50 specially-trained officers directly into troubled neighborhoods, allowing them to become a part of the community.

Connie Rice, co-director of the Los Angeles-based Advancement Project, echoed Beck’s call for change and community-based approaches to policing, making a comparison to the war on drugs.

“We’ve been stuck on stupid,” she said. “The only thing that was a bigger failure than the war on gangs was the war on drugs.”

Rice says Los Angeles’ new approach is innovative and a model for the rest of the country.

“Mass incarceration doesn’t work,” she added.

Donyee Bradley, a Gang Outreach Worker who grew up a gang member in Washington, D.C., said the most important thing for everyone working to improve communities and stop gang violence is to stay the course.

“An artist gets to see the finished product,” he said. “In what we do, we don’t get to see that.”

Speaking to the crowd, Bradley thanked the researchers at the college.

“Through your research, we are changing lives,” he said. “We are changing the mind sets of families and communities.”

But for many in the criminal justice system, incarceration is only the beginning. For convicted person’s, transition back into society is fraught with challenges, says Ann Jacobs, director of the John Jay Prisoner Re-Entry Institute.

“No one sitting in this room wants to be judged for the rest of our life on the worst decision we ever made,” she said.

“No one sitting in this room wants to be judged for the rest of our life on the worst decision we ever made,” she said.

But, she says, not enough is understood about re-entry.

“Twelve years ago the term re-entry didn’t exist and there was no body of research,” she said.

In Jacob’s view, every conviction becomes a life sentence because of the stigma society has placed on ex-offenders.

“The words ‘felon’ and ‘convict’ are labels we put on people for the rest of their lives,” she said. “Do we really think someone who is a former convict shouldn’t be a security guard at the Statue of Liberty?”

Most people who are convicted are not a public safety threat, said Margaret Love, a former pardon attorney for the United States Department of Justice.

“We even know how many people have misdemeanor convictions,” she said. “There are upwards of 65 million [people with convictions] and 92 million separate records of criminal convictions.”

She added, “It brings home how pervasive this problem has become. But dealing with the problem on a mass basis can ignore the human story.”

Former convicts are treated differently, said Sheila Rule, founder of the Think Outside the Cell Foundation, an organization providing education and personal development tools to those in prison, the formerly incarcerated and their families.

“This was a population who were demonized, stigmatized, marginalized and ignored,” she said. “It’s not that people oppose these men, women and children; they just don’t think about them.”

According to Love, there are more than 35,000 laws across the United States excluding former convicts from benefits.

“Today, a convicted status is the primary means, other than citizenship, of assigning legal status,” she said. “It is the one permissible basis for discrimination.”

As a response, Rule says Think Outside the Cell is starting an “End the Stigma” campaign.

“We have much work to do and it is not easy,” she said. “But it is critical.”