![]() As the holiday season rolls around and many of us are cherishing time with those we love, families separated by incarceration continue to face barriers when trying to maintain a sense of support and connection with their loved ones.

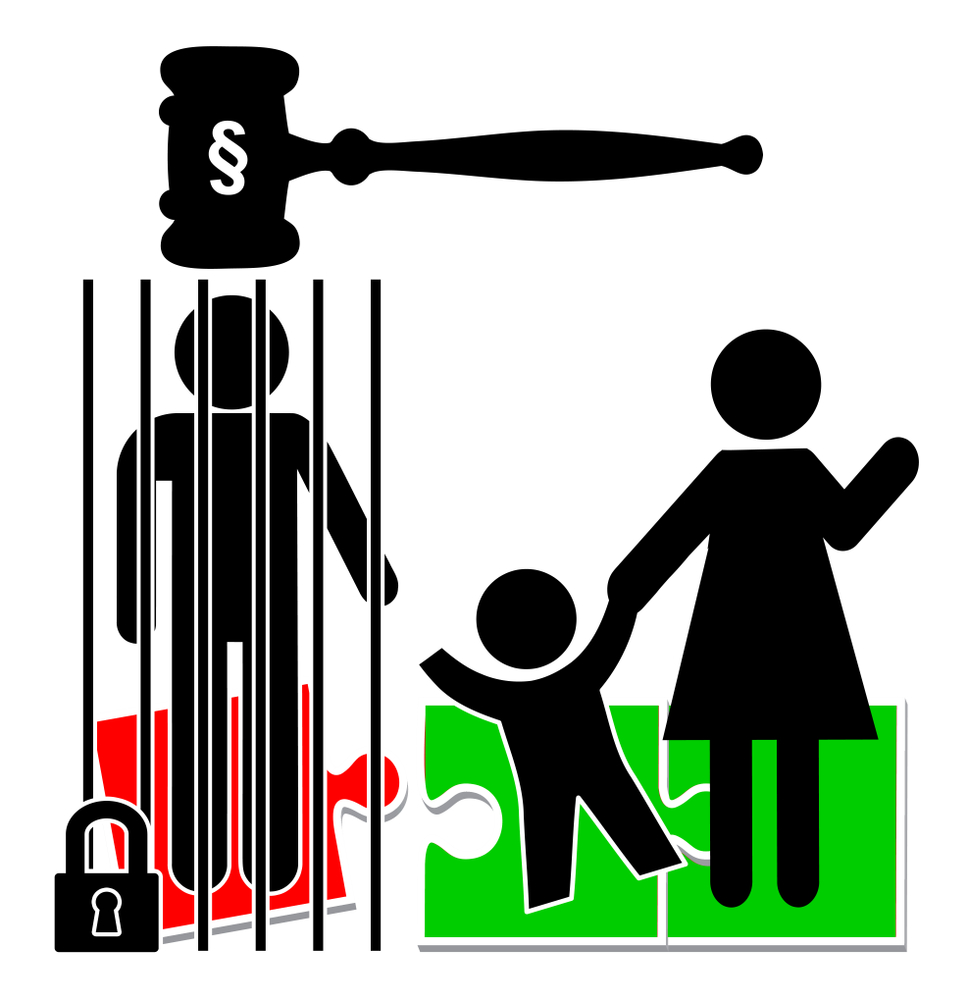

As the holiday season rolls around and many of us are cherishing time with those we love, families separated by incarceration continue to face barriers when trying to maintain a sense of support and connection with their loved ones.

The harm of incarceration ripples beyond each person serving time away from their family and community. The decision to incarcerate individuals and separate families directly impacts the lives, minds and futures of those on the ‘outside.’

Renee Menart

Children with an incarcerated parent are particularly vulnerable to the negative impacts of such a painful and traumatic experience. At a young age, 2.7 million children across the U.S. are forced to navigate the experience of a parent’s incarceration, conservative estimates show. That number expands to more than 5 million when we consider not only the children with a parent currently in prison, but also those whose parent was incarcerated in the past. The impacts of incarceration run deep across communities of color in the U.S. with 1 in 9 black children and 1 in 28 Latino children having experienced a parent’s incarceration.

Whether a child’s parent is currently or previously incarcerated, the implications are long-lasting and life-altering. Children with adverse childhood experiences, including a parent’s incarceration, may face mental health challenges that continue well into adulthood. In some states, including Iowa and Kansas, a parent’s rights can be involuntarily terminated because of a felony conviction or imprisonment, leading to further disruption for a child’s home life. And if a child’s incarcerated parent was their primary caregiver, as is the case for 75 percent of incarcerated women, they may come into contact with the foster care system.

Additionally, the economic well-being of children and their families are put at risk when a parent is incarcerated — especially the children of over half the fathers in state prison who were their family’s primary breadwinners. Even after a parent returns home, they often face employment barriers including discrimination and ineligibility for many occupational licenses, which can further a family’s financial instability.

Don’t overlook kids at arrest

Any time a parent or caregiver comes into contact with the justice system, the needs of their children must be considered and prioritized. Whether families are separated for years due to a prison sentence, often hundreds of miles from home, or for a few days in jail, exposure to the justice system at all points can have lasting implications for children.

At one of the earliest points of justice system contact — an arrest — the presence of a child is often overlooked at the scene. Parents are frequently arrested and even handcuffed in front of their child, and many law enforcement agencies do not have protocols on how to interact with children under such shocking circumstances. Children who have witnessed the arrest of a household member are far likelier to experience post-traumatic stress symptoms than children who did not witness an arrest. In an effort to reduce such harm, treating a child with kindness and care is not only the right thing to do but a critical practice for the health and well-being of our communities.

Even a few hours in a courtroom can prove traumatic for children, but many caregivers have no choice but to bring their children with them when they are required to appear in court. An innovative program originated in San Francisco, the Children’s Waiting Rooms offered by the Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice (CJCJ), combats this preventable harm by providing care for children in a positive and safe setting at the courthouse. The program space resembles a classroom with its colorful decorations, toys and art supplies. Such a seemingly simple service has been providing care for thousands of children each year since it began as the first of its kind in 1991. Since then, numerous counties across California have opened similar facilities and foreign judges use the Children’s Waiting Rooms as a model for their own countries.

Beyond the courtroom, positive and safe environments must be offered for the 2.7 million children who have a parent currently incarcerated. That is 1 in 28 children who are often left asking: Where did you go? Why did you leave me? What do I do now? For these children, opportunities to meaningfully engage with their parent without traumatizing and dehumanizing visitation procedures can help mitigate some of this confusion and build a pathway for ongoing and supportive relationships within families.

Dinky Manek Enty, CJCJ's deputy director and supervisor of the Children's Waiting Rooms, which has historically supported family visitation in San Francisco County Jails, emphasizes, “A designated family visiting room decorated with child-friendly paintings and murals and fully supplied with various games, toys and art supplies is the ideal space for child and family contact visits.” The provisions for such a space at San Francisco’s archaic county jail were made despite facility and fiscal barriers, proving it is possible to develop appropriate family visiting spaces in the face of challenges through committed leadership, she says.

Kids need contact, not video calls

Despite the importance of contact between incarcerated parents and their children for building and maintaining relationships, nearly 60 percent of incarcerated parents in state prison and 45 percent of parents in federal prison in 2004 reported that they had never had a visit from their child or children. Families often face considerable distances to correctional facilities and are forced to foot the bill for costly phone calls (with Texas and New York City leading in cutting these costs). Further, many facilities restrict visits to non-contact or even video visitation, and barriers to family engagement are all too common across the U.S.

“One-on-one family contact visits are particularly critical for younger children whose healthy development can flourish with positive human contact with their parent,” Enty says. In particular, babies benefit from loving contact like hugs and kisses but parent-child bonding is put at risk when visits are limited to seeing a parent behind glass or hearing their voice by phone.

As we celebrate the holidays among family and friends, let us not forget the children and parents separated by incarceration this season and the importance of promoting these family relationships in practice. Federal, state and institutional policies must reflect our nation’s values by addressing the all-too-often hidden costs of incarceration on families and future generations.

Potential solutions include training for law enforcement on how to engage with youth they encounter during an arrest, and direct service programs to help mitigate trauma for families impacted by the justice system by providing child-friendly spaces at courthouses, jails and prisons.

In the new year, juvenile and criminal justice solutions must consider the wide reach of incarceration on families and children in order to end the cycles of harm within our communities.

Renee Menart is a communications and policy analyst with the Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice in San Francisco.

Im interested in this program.

Great article! For information on a great program to use with children at arrest, or when any sort of child trauma occurs which involves police in the home, see: http://www.handlewithcarewv.org or contact WV Center for Children’s Justice, WV State Police, 725 Jefferson Road, South Charleston, WV 25309

(304) 766-5881