Following another Chicago summer during which many youth were slain in gang or drug disputes, there was concern on both sides of the Chicago teachers’ strike this week about the safety of the children whose school doors have been shut during negotiations over a new contract.

Following another Chicago summer during which many youth were slain in gang or drug disputes, there was concern on both sides of the Chicago teachers’ strike this week about the safety of the children whose school doors have been shut during negotiations over a new contract.

There was little patience and much anger leading up to, and following, the breakdown of talks late Sunday, which picked up again with the new week but so far have failed to stem the first strike here since 1987. That’s a quarter century of relative labor peace in a city where walkouts and the delay of the school year were regular.

While remembering those union battles might stretch the memory of many Chicagoans, there's little need to stretch the imagination about what might happen if minors are left unwatched or unsupervised as parents return to work. Consider: Through the first week of September, homicides in Chicago were up nearly 30 percent over last year to 366, and overall shooting incidents were up 10 percent.

While the crime tally is still much lower than during the high violence of the 1980s and 1990s, the summer toll pushed Mayor Rahm Emanuel into a tricky political corner. For example, Emanuel was criticized for taking time out to speak during the Democratic National Convention, despite the seeming chaos at home in Chicago.

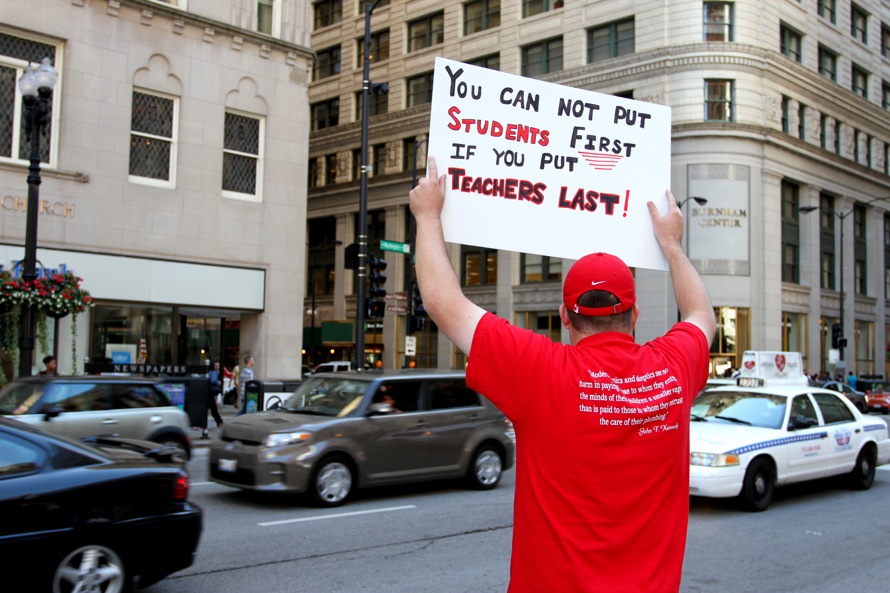

Also backed into the corner -- with some passersby screaming such insults, as “filthy scumbags” at the thousands of strikers who jammed downtown streets -- were Chicago school administrators, union leaders and teachers, as well as police Superintendent Garry McCarthy.

U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan has weighed in, as well as others from the national stage, and Chicago once again landed in the spotlight.

The strike officially began Monday morning, soon after negotiators for the Chicago Public Schools board walked away from talks. And so, 29,000 Chicago Teachers’ Union members took an absence from their jobs and staged what threatens to be a lengthy protest. Late Tuesday, talks again ended with no deal -- and union president Karen Lewis said the teachers and city had only solved a handful of the dozens of issues on the table. For its part, City Hall was saying the two sides were getting closer to a resolution.

With the strike, CPS enacted its contingency plan, which requires at least 144 CPS schools to open their doors to students from 8:30 a.m. to 12:30 p.m. each day the strike continues. CPS will not provide transportation to these schools, which could remain open until at least 2:30 p.m. come Thursday -- and parents need to sign up their children beforehand or call 311.

open their doors to students from 8:30 a.m. to 12:30 p.m. each day the strike continues. CPS will not provide transportation to these schools, which could remain open until at least 2:30 p.m. come Thursday -- and parents need to sign up their children beforehand or call 311.

Many are worried that as the school day shortens during the strike, or is eliminated entirely at some schools, crime or neglect will increase against and among youth.

Chicago Teachers Union political director Stacy Davis Gates said she was worried that City Hall's leadership on crime was lacking -- and that teachers are being asked to absorb the responsibility.

“If we're really worried about this violence, why are our schools without nurses and social workers that could actually help to absorb the trauma that these kids experience as a result of this high murder rate?” Davis Gates said.

She continued: “We're asking them to come back into a classroom and bubble in A, B, C and D into a test and to get a test score from it. But we're not providing them with people who can help them analyze and synthesize the experiences they're coming into the building with. We don't have mental health care clinics in our communities. They've been shut down. We know a great majority of our students come from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, where health care is not always the best. And we're not providing those vital resources to them.”

Davis Gates also said she is warning people “not all of our children are criminals.” That is a sentiment echoed by children and parents across the city -- but one with which observers and officials in the police houses and schools are concerned people will get too comfortable or complacent.

Indeed, seeing this concern, many businesses, foundations and other organizations were trying to bridge the gap with ad hoc and improvised programs to keep youth, especially in more troubled pockets of the city, occupied and cared for. This continued -- and was stepped up – Tuesday, even as CPS said plans were in the works to extend the hours of the shortened day in schools that were opened.

CPS social worker Doreen Heredia said she is striking because there are not enough social workers per school.

“We’re assigned based on special-needs,” Heredia said. “But there’s so much more that needs to be taken care of — children in crisis, families in crisis, homelessness, poverty, job loss. I deal with a lot of undocumented parents, so yeah I could use some more social workers in this community.”

In order to go on strike, CTU had to get 75 percent of its members to vote for a strike authorization. The teachers overwhelmingly voted for a strike, with 98 percent consent. The CTU's Davis Gates said union members were “disappointed it has come to this.”

“It's offensive and very disconcerting that here we are, but our members are willing to make a stand,” Davis Gates said. “This is more than the wages and the benefits and about the type of education that we believe, as the experts, our students are deserving of here in Chicago.”

Teachers started forming picket lines in front of the CPS headquarters and in front of their respective schools Monday morning. Davis Gates said until a compromise or settlement is reached, CTU members will continue to strike.

CPS parent Elle Kerlegan said if parents understood the role teachers play in their child’s life, then they would be supportive of the teachers on strike.

“I think next to parents, teachers do a big job in inspiring your kid to go further their education and achieving bounds that they wouldn’t otherwise achieve because of their circumstances,” Kerlegan said. “You don’t know where these kids come from, the type of family life they have.”

There was also real worry among some about drag on students' learning during the stretch of the strike.

"Every day that they're not in school is a day that they're not learning," said Pamela Barber, a 4th grade teacher with seven years experience. "And so, my concern is that the things that we had set up for them, like in our lesson plans and stuff, they won't be lost, but we'll have to play catch up when we do go back to school. And then there are kids who come to school with deficits anyway, so whatever plans we had for them, you have to work triple hard to even get them caught up to where they're supposed to be - if you can get them caught up. So they're missing out."

The issue of safety also resonates with Barber, who went to CPS and has a son who attends public school:

The issue of safety also resonates with Barber, who went to CPS and has a son who attends public school:

"Why would you have them come to school from 8:30 to 12:30?" she said. "That's not a whole school day, so what are you going to do with them after 12:30? So are you really concerned about their safety if you're not at least keeping them in school as long as they would if they were in school regularly."

With additional reporting by Lorraine Ma and Natalie Krebs.

Audrey Chang is a reporter for The Chicago Bureau.