CHAPEL HILL, N.C. — This is the first in a series of reports investigating the history and development of youth justice in the state.

With the historic change of Raise the Age come questions about what it took to pass it and where juvenile justice in North Carolina goes from here.

We’ll be examining what it took to reach this landmark decision and what happens once it takes effect at the end of this year.

The Southern brand of justice has been less forgiving of youth crime. But a fundamental change to juvenile justice in North Carolina represents something of a break from the past.

“In North Carolina, as part of the Bible Belt and living in the South, a lot of people who are from here value accountability, and we’ve been really punitive in terms of how we’ve dealt with children historically,” said Jonathan Glenn, associate project director for the Juvenile Justice Institute at N.C. Central University.

North Carolina Central University

Jonathan Glenn

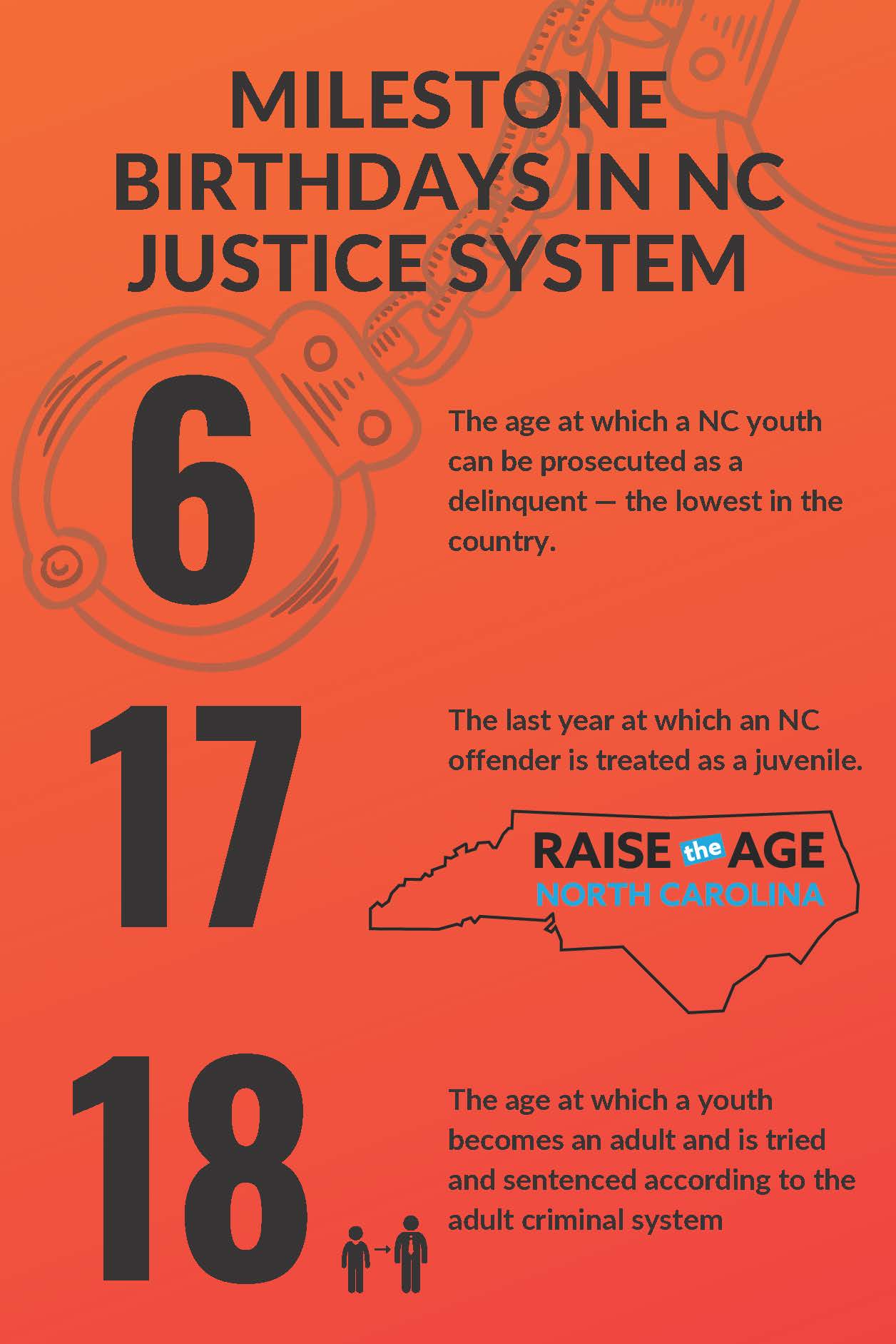

Raise the Age, which increases the age of criminal responsibility to 18, takes effect on Dec. 1. The last state to pass this legislation, North Carolina is now eye-level with the way other states prosecute juveniles.

Designed to include most 16- and 17-year-old offenders in the juvenile system, the Juvenile Justice Reinvestment Act (JJRA) takes a notable step toward criminal justice reform.

But taking that step leaves a massive gap.

Consider: A teen of 16 or 17 who commits even a crime before Raise the Age takes effect will still be tried as an adult, even though the bill was passed in June 2017. When the JJRA was being written, it didn’t account for these youths.

Youths in limbo

Juvenile arrests in the U.S. are clearly in decline — down nearly 60% nationally from 2007 to 2017 — as some remedies like teen court and diversion are increasingly used. But Congress and state legislatures are still uncertain about what to do with kids already in the system.

Eric Zogry, head of the North Carolina Office of the Juvenile Defender, estimated there are thousands of juveniles in limbo — 2½ years’ worth of youth convicted of misdemeanors and low-level felonies who will still be tried as adults.

They will continue through a process that some organizations, like the Durham, N.C.-based Youth Justice Project, call detrimental to their educational and social development.

Eric Zogry

“You can hold a student accountable without being punitive,” said Peggy Nicholson, director of the Youth Justice Project. She emphasized a focus on alternatives that keep young people connected to positive influences and opportunities.

The word “justice” needs to be reclaimed “in a way that doesn't mean punishment,” she said.

Reclaiming could mean compelling the justice system to recognize the nuance of age and how it can contextualize a situation. Advocates say the old system doesn’t take into account the psychology of those it deems youth or adults.

“There really isn’t much difference between a 15-year-old mind and a 16-year-old mind, or a 17-year-old mind and a 20-year-old mind,” said Jonathan Glenn, associate project director for the Juvenile Justice Institute at N.C. Central University. “So, unfortunately, the law was written in such a way where those youth are being held to a standard that is, for all intents and purposes, just not fair.”

Peggy Nicholson

But for the youth in the gap, the clock can’t be turned back.

Some expungement bills and restorative justice programs have been discussed to retroactively address not just the youth in limbo, but also current juveniles who fell into the adult system in the years it took to pass Raise the Age.

Even before it passed, supporters of JJRA feared the bill would be voted down or not funded appropriately, and that’s still a worry for some practitioners, Glenn said.

Miller v. Alabama frees Illinois man

And it’s not just the South that has been pushed to re-examine the way it processes and sentences youth versus adults. In Illinois, for example, scrutiny and change have come to juvenile life without parole.

In 1992, Marshan Allen was sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole when he was 15. Allen was helping his brother recover stolen drugs but was charged with two counts of first-degree murder even though he didn’t fire any shots.

Allen spent 24 years in Illinois prisons until he was released in 2016, due to Miller v. Alabama, the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision that mandatory juvenile life without parole is unconstitutional. However, the decision is not a flat ban on juvenile life sentences; it only made them not mandatory and required a sentencing hearing.

Currently, there is no federal law definitively prohibiting discretionary life sentences for juveniles.

Marshan Allen, pictured in 1992 at 15, the age at which he was sentenced to juvenile life without parole.

And the caveat is that this only applies to offenders who are eligible to be tried as youth, and that depends on what a state considers to be a youth. Take Allen, now 43. If he had been arrested in North Carolina and was just a year older, he might still be incarcerated.

New bills can be signed into law, but they don’t always handle their fallout. That’s partly why some youth won’t be protected by Raise the Age.

The other part is that North Carolina still enforces certain laws that work against Raise the Age and keep juveniles in the adult system.

As a state with a “Once an adult, always an adult” provision, youth who start in the adult system remain there for any future offenses. North Carolina also considers children as young as 6 delinquents, the lowest threshold of any state.

No-tolerance policy traps ‘child antics’

Cristina Becker, an attorney for the North Carolina American Civil Liberties Union, served as a public defender in Mecklenburg County, which contains Charlotte, for nearly three years. Becker worked primarily with indigent teenagers and adults in criminal cases.

Some of the cases she defended shocked her.

One of her clients was a 16-year-old who was charged as an adult after he took a quarter from a wishing well in the mall. An officer chased and tackled him, she said.

In these situations, Becker explained, it’s not the swiping of the quarter that leads to arrest, but the act of running away from the officer. That can become resisting arrest.

“I mean, these are really like child antics,” she said.

She had to explain this to her client three or four times before he registered that he had done something that could lead to jail time. Then, she said, it was pure panic.

Becker also recalled a colleague with a client who was charged with simple assault when he threw a strawberry at another student in the school cafeteria.

“With sort of a no-tolerance policy — which should never exist, there should never be zero tolerance for anything — they, 16- and 17-year-olds, get automatically funneled into the adult criminal system, and there’s no discretion as there are in other states where they decide whether or not the charge is serious enough to try them as an adult,” Becker said.

“People knew that juveniles were just stupid,” Allen joked.

But reckless behavior at school can get swept into the justice system through referrals. In North Carolina, more than 40% of referrals to the juvenile justice system came from schools in 2016.

“When you represent kids, a lot of the time they do stuff, and they’re not really thinking,” Zogry said. “People refuse to acknowledge their own part in perpetuating a system where kids of color are over- identified, overly disciplined, overly punished for behavior that could easily be addressed administratively.”

This school-to-prison-pipeline can make juveniles first-time offenders, Becker said. And while repercussions for offenses this minor can be mitigated by diversion programs, they are costly, though it varies from place to place.

“Even if they have some small, part-time, after-school job, they do not make enough money at that job to pay for this,” Becker said. “And not only that, but a lot of these programs are after school, on the weekends, at night — at the same time that they would actually be working a job.”

That’s where Becker identified another problem that arose from a well-intended solution. Often, 16- and 17-year-olds are financially dependent, so costs fall on family, she said.

‘Punishment first’

In some places, the public’s attitude is still “do no crime, do no time,” Allen said. Being compassionate and flexible is not a historically successful political platform, he said, so as long as those beliefs remain, tough-on-crime representatives will, too.

“The issue is the fear of being seen as soft on crime,” he said. “It’s politically expedient to be hard on crime, and it actually rewards for it. You can be hard on crime and get voted to office.”

The issue Allen and Becker cite is that a wide array of behaviors are referred to the criminal justice system. They are treated wholesale as individuals of varying charges and ages face the same sentence. Even if behavior isn’t violent or threatening, it could be criminalized.

Molly Weisner

.

Becker said the majority of her juvenile clients were charged with minor things. When she was a public defender, she sometimes asked why the clients were arrested in the first place.

“Sometimes, I would literally get shrugs,” she said. “… If you still have a culture that is based on punishment first, everything else is going to be disciplinary.”

This culture seems to live on in the schools, too. In the 2017 Juvenile Justice Report provided by the North Carolina Department of Safety, one of the listed accomplishments for the year included “continued to work with schools employing resource officers and school districts to prevent unnecessary complaints going to court through consultation, diversion services and special local initiatives such as school-based court counselors. ”

But in the same year, three of the top five juvenile offenses were misdemeanors. The top two school-based complaints were also for misdemeanors: simple assault and disorderly conduct at school.

And of the just over 28,000 juvenile complaints the state received in 2017, 60% were approved for court instead of diverted or closed.

Student codes and SROs

One entry point to the pipeline is maintained, in part, by vague language in student codes of conduct that allow administrators and teachers to default to calling law enforcement, even if the initial behavior isn’t illegal or violent.

For example, the Student Code of Conduct for Rogers-Herr Middle School in Durham outlines behaviors that are “considered violent acts that are illegal and covered by School Board Policy.”

Room for interpretation still exists; codes may allow a principal to “request assistance from law enforcement when necessary,” as the Durham School of the Arts Code of Conduct says. Though DSA and some others have an extensive graduated disciplinary matrix that takes age into consideration, some students claim it’s another well-intended but ultimately permeable fix to juvenile crime.

“I look at the situation as putting a Band-Aid on a deep gash that will stop it from getting worse, but it will not at all fix the situation,” said Elijah King, 17, a senior at Riverside High School in Durham.

It’s also not just language that outlines expectations for student behavior, but documents that define a school resource officer’s power, too.

These documents, called memorandums of understanding, are agreements between the local sheriff’s department and a school system, explained Hank Snyder, a former instructor at the North Carolina Justice Academy. But the officers on duty at schools don’t have much say in their own job description, he said.

“I doubt that the individual SROs have direct input [in MOUs],” Snyder said in an email. “The SRO supervisor may or may not have SRO experience. Also, the SRO supervisor may or may not ask their SROs for input.”

Unfortunately, Snyder says, instances of school resource officers being violent or threatening stem from laziness or unwillingness to be in the position they’ve been assigned to.

This can lead to SROs being overused as heavy-handed disciplinarians, Becker said.

“There was the creation of the SRO and the idea that placing law enforcement in schools would somehow make schools safer and build more community trust, and it did the exact opposite,” Zogry said. “More minor offenses were being charged and brought to court, and there has been no data to show that schools are, in fact, safer.”

That’s where Raise the Age comes in again.

School-justice partnerships that encourage graduated, situational models to minimize court referrals became a formal component of Raise the Age, but only seven of North Carolina’s 100 counties have implemented such partnerships.

And even after the JJRA takes effect at the end of this year, discretion by schools and law enforcement lingers in the systems that feed into the juvenile justice system.

Going forward, Glenn said the concern is whether the state can commit to funding the diversion programs, juvenile facilities and school-level counselors that can offer support to prevent crime.

But, as North Carolina history shows, there hasn’t been robust support for funding these efforts that would move the needle, Glenn said.

But he said he fears that the “innovative and progressive efforts to deal with juvenile crime here in North Carolina,” like Raise the Age, will produce weak outcomes if the state cannot follow through and fund them.