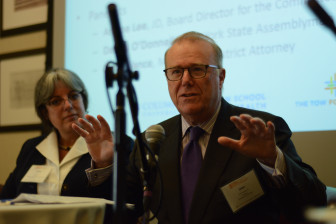

Gwen McClure / JJIE

Gladys Carrión, commissioner of New York City Administration for Children’s Services (ACS), speaks at a conference this week at the Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health. The conference focused on incarceration as a public health issue.

NEW YORK — Public health and criminal justice experts from across the country gathered this week to discuss mass incarceration in the U.S. in the context of a public health issue, and highlighted the need to view the problem through a different lens.

The conference, titled “A Public Health Approach to Incarceration: Opportunities for Action” and hosted by Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health, focused on the incarceration of all age groups, but highlighted topics specific to youth including education, community support and recidivism rates of young men who have misdemeanors.

“This conference is really about what should schools do in the face of a nation that’s so caught up in a policy of mass incarceration,” said Robert Fullilove, associate dean for Community and Minority Affairs at Mailman School Of Public Health.

Gwen McClure / JJIE

Experts discuss incarceration, recidivism and the importance of helping children to stay out of the justice system during one of the many panels at this week's conference.

Experts discussed the importance of data and research, citing city blocks known as “million dollar blocks,” not for the amount of money spent on resources but rather for the cost of incarcerating people from that block. Other conversations revolved around the importance of evidence-based research in order to know and implement models that actually work.

“Research without advocacy is dusty books on the shelf,” said Angela Aidala, a research scientist from Mailman School of Public Health. “But I’ve learned that advocacy without research is a temper tantrum.”

Multiple participants and panelists shared personal stories of incarceration and emphasized the importance of listening to the expertise of people who speak from experience. Mujahid Farid, lead organizer of Release Aging People in Prison Campaign (RAPP) told the audience that by the time he had completed 15 years in prison he had earned several college degrees and created new programs. He was denied parole and remained incarcerated for another 18 years.

“That was really a waste of resources that could have contributed to communities,” he said. “And that’s what’s going on across the board.”

“That was really a waste of resources that could have contributed to communities,” he said. “And that’s what’s going on across the board.”

Fullilove teaches a class inside a correctional facility and hopes to see the young men he teaches go back into their communities as public health educators. Believes that this is an important opportunity for public health education. These men are uniquely positioned to educate their communities, and he hopes to see the public health field shift its collective view of these young men and take advantage of this group of trained individuals.

“We’ve been talking about folks who are on the inside as part of the problem,” he said. “We’ve been talking about them as the focus of much of our research.

Gwen McClure / JJIE

Bryan Stevenson, founder and executive director of the Equal Justice Initiative, speaks with other juvenile justice experts and advocates at this week's conference at Columbia University.

Experts also discussed the importance of helping children to stay out of the justice system. In a breakout session Tuesday on juvenile justice and health, facilitator Gladys Carrión, commissioner of New York City Administration for Children’s Services (ACS), emphasized that simply keeping children out of justice system after they’ve been involved once is not a marker of real success. For young people to be successful they need access to education, community support and adult figures on which they can depend. For this reason, structures currently in place are not sufficient.

“Foster care is my front door to juvenile justice,” she said. "There have to be other pathways."

Carrión discussed the opportunity for partnerships with other fields, including schools of public health, and the importance of keeping children in their communities. She also addressed the $362,000 yearly cost of keeping children incarcerated in New York City.

“You get absolutely nothing for $362,000,” she said. “It’s a training ground for criminality.”

There was agreement that these issues cannot be talked about in isolation, and that racial disparities must be addressed. Carrión said that she would have difficulty finding a young white person in her system, referring to the fact that young black and Latino men make up the majority of incarcerated youth. Panelist Cheryl Wilkins, associate director of Columbia Justice Initiative, addressed the role that racial profiling plays, in addition to other factors such as the differing experience a child may have if they have a parent who is incarcerated.

There was agreement that these issues cannot be talked about in isolation, and that racial disparities must be addressed. Carrión said that she would have difficulty finding a young white person in her system, referring to the fact that young black and Latino men make up the majority of incarcerated youth. Panelist Cheryl Wilkins, associate director of Columbia Justice Initiative, addressed the role that racial profiling plays, in addition to other factors such as the differing experience a child may have if they have a parent who is incarcerated.

“Kids are also stigmatized for something they didn’t even do,” she said. “As a society we have to stop that.”

Financial supporters of The JJIE may be quoted or mentioned in our stories. They may also be the subjects of our stories.

Pingback: Mass Incarceration: A Public Health Issue | j u s t c r i m