Art, Writing Shows What Young People Want From Police

|

A police officer kneels down face to face with a child.

“I’m sorry I stole,” the child cries.

“It’s OK. Just don’t do it again,” the officer replies.

Juvenile Justice Information Exchange (https://jjie.org/author/jjie-org/page/24/)

A police officer kneels down face to face with a child.

“I’m sorry I stole,” the child cries.

“It’s OK. Just don’t do it again,” the officer replies.

In the early morning hours of April 27, 2016, Kraig Lewis was up late studying for his statistics final. A graduate student at the University of Bridgeport in Connecticut with only nine credits left until completing his MBA, Lewis planned to go to law school next. At about 4 a.m., Bridgeport Police banged on his door.

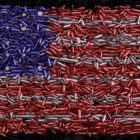

Guns are everywhere you think they’re not. Guns have been found on the floor of a movie theater and in the diaper aisle of a big box retailer. They aren’t just slid under a mattress at home or tossed up to the top shelf of a closet; they’re lying in a pile of leaves, or behind a toilet in an airport.

The mother left and two teens were alone in the house. It took the 13-year-old son 10 minutes to find the gun. It was loaded and in a bottom dresser drawer covered by one piece of clothing. It might as well have been on the fireplace mantle.

In recent years, juvenile justice practitioners, researchers and advocates have raised awareness of the harms of room confinement or isolation of youth in detention and residential facilities. Research and empirical knowledge teach us that the practice can negatively impact youth’s developing brains and emotional health, impair youth’s relationships with staff, limit youth’s access to important programming and treatment, and ultimately lead to unsafe facility environments.

Nataya Foss remembers being told that she would soon have to leave the shelter. She had been staying in one of Washington state’s few shelters for unaccompanied homeless minors, but because of restrictions that come with government funding, the shelter could house her for only three weeks. Her time was almost up.

On June 4, after 44 years in office, Broward County’s state attorney, Michael Satz, announced he’ll be stepping down. His departure could herald a sea change for the county’s criminal justice system, which has been marred by high-profile crimes and allegations of racially biased policing.

Best practices for state advisory groups as federal grant money has diminished is the focus of a new report from the Coalition for Juvenile Justice.

My daughter Taylor has been raised in adult jails and prisons since she was 15. She is now 19 and it will be another six years before she can come home. At that point, as she navigates being an adult in a world she’s never known, she’ll carry the burden of probation until she’s 35.

As the United States grapples with how to best address juvenile and youthful offenders, criminal justice reform is focusing on the best avenues for dealing with low-level drug possession offenses. Organizations that research best practices with youthful offenders, such as the National Institute on Drug Abuse, suggest that the most effective approach is to reduce incarceration in favor of family- and community-based interventions.