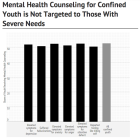

Photo by Justice Policy Institute

One of the greatest obstacles to reforming the juvenile justice system is the fear that “going soft” on juvenile crime will pose a threat to public safety, either by setting youthful marauders loose upon a defenseless public or by removing the supposed deterrent effect of harsh and mandatory punishments. A second obstacle is the belief that any alternative to the current system of punishment and confinement will cost more, a particularly unwelcome proposition at a time when many states and communities are experiencing severe budget shortfalls. A new report from the Justice Policy Institute, a national nonprofit organization in Washington, D.C., and funded by the Tow Foundation, provides evidence contradicting the assumptions behind both objections to reform. “Juvenile Justice Reform in Connecticut: How Collaboration and Commitment Have Improved Public Safety and Outcomes for Youth” details a series of reforms in the Connecticut juvenile justice system since the 1990s, and the positive changes observed in the state since those reforms were instituted. In the report, author Richard Mendel states that the Connecticut juvenile justice system today is “far and away more successful, more humane, and more cost-effective than it was 10 or 20 years ago” and attributes these changes largely to the state’s willingness to re-invent its system, based on “the growing body of knowledge about youth development, adolescent brain research and delinquency.”

The most significant of these changes include ending the criminalization of status offenses (e.g., truancy, running away), ceasing to treat 16- and 17-year-old offenders as adults, building a system of community alternatives to confinement and sharply reducing the number of juveniles sentenced to confinement. Connecticut also developed programs to address the specific needs of girls in confinement, to address racial disparities in the juvenile justice system, and to reduce school-based arrests and out-of-school detentions.