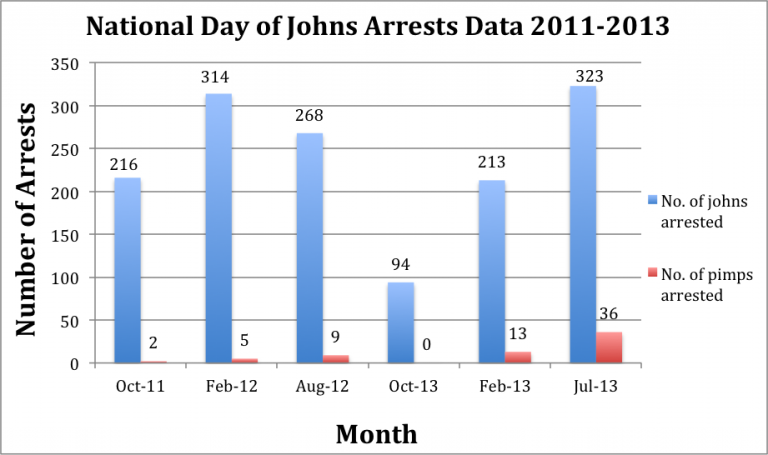

Graph shows trend in arrest data for johns and pimps during National Day of Johns Arrests from 2011-2013. Source: Demandabolition.org

CHICAGO — When Marelyn Garcia met the man who would become her boyfriend, little did she know he would become the trigger to her heroin addiction, and eventually her pimp, after he coerced her into working the streets to fund their addiction.

It was in a Chicago club one night in 1996 where Garcia was first introduced to him.

“It was a dating relationship to begin with, until we became drug addicts,” Garcia said. “Once he established that we were a couple, I did it out of so-called love.”

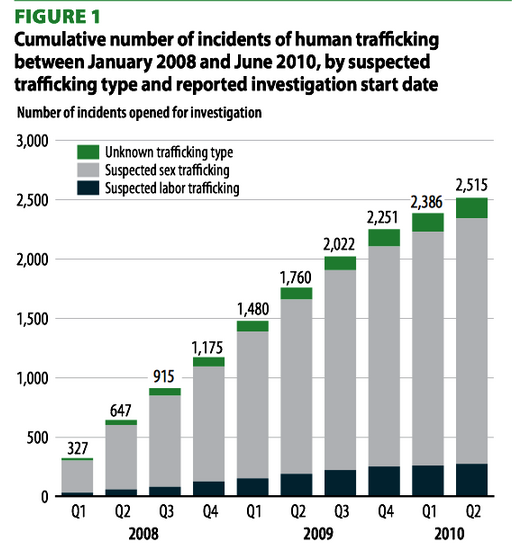

Human trafficking incidents in the U.S. have been increasingly steadily, with a cumulative total of 2,515 known incidents by mid-2010. A 2003 New York Times article signaled Chicago was fast becoming the “national hub of human trafficking.”

Human trafficking incidents in the U.S. have been increasingly steadily, with a cumulative total of 2,515 known incidents by mid-2010. A 2003 New York Times article signaled Chicago was fast becoming the “national hub of human trafficking.”

Amy Alvarado, a human trafficking specialist at the Cook County State Attorney’s Office, said this is because Chicago is a large “convention city” with a “huge international airport.”

Recent hotline statistics from the National Human Trafficking Resource Center (NHTRC) show Illinois had the fifth highest call volume, falling behind only New York, Florida, Texas and California.

Sex trafficking victims are typically solicited in Chicago suburbs in places such as massage parlors and gentlemen’s clubs because locations downtown are heavily monitored by the police. Gangs, especially those on the West Side, also use human trafficking.

- Graph shows percentage of respondents, all ex-pimps, who identified with the distinct household characteristics. Source: Northeastern University

The situation has worsened over the past five years, particularly because of the Internet—“Traffickers or predators can [now] sit anonymously behind computers,” said Joanne Bieschke, Deputy Director of the Cook County Youth Services Department. Online traffickers typically form cyber relationships with young teenagers, steadily gaining their trust and making them feel like nobody but the [trafficker] can empathize with their struggles.

Those especially vulnerable to these deceptions are individuals experiencing conflict in school or at home, who are seeking escape from their current situations.

Popular websites frequented by johns, men who pay for prostitution services, include classifieds sites like craigslist and backpage. Johns also use online forums to share their ‘adventures.’ “They have sex addiction,” said Mary Bonnett, director of a play on sex trafficking in Chicago. “They have a distorted view of sexual relationships.”

An unimaginable detour

While in the John F. Kennedy International Airport for a supposed transit to Chicago, never in her wildest dreams did migrant worker Shandra Woworuntu anticipate being kidnapped to a brothel by traffickers.

Amidst the 1998 political turbulence in Indonesia, Woworuntu lost her job as a banker. Because her husband had passed away, Woworuntu accepted a Chicago hotel job advertised in a newspaper — it turned out to be fabricated.

Although she had spent $3,000 to secure the job, Woworuntu never made it to Chicago, and the cost paled grimly in comparison to the price she would have to pay once she was trapped in New York City, forced to sell her body against her will.

Although Chicago is the apparent “national hub” of human trafficking, with stop-offs en route, some people like Woworuntu are intercepted on their way to the city.

“I flew to [New York City],” she said. Someone picked me up, gave me to someone else, [and] said there was no place to stay before we went to Chicago, where I was supposed to work in a hotel.”

Woworuntu was not alone in having been duped by a false job offer — she was kidnapped in a group of other unknowing foreign women who were hopeful for new lives in the U.S.

“We were [being] sold to another trafficker… [it] was an organized crime with traffickers of about five nationalities: Malaysian, Indonesian, Taiwanese… Chinese, [and] American.”

Shadow Town

Prior to writing the script for Shadow Town, Bonnett conducted 18 months’ worth of interviews with players in the Chicago sex trade, including victims and pimps.

“I realized what a powerful tool theater was … I saw that it really created change,” she said.

The play, which portrayed sex trafficking through the eyes of a pimp, “allowed for [the audience] to see how he does what he does, and why those girls are so drawn to him."

Bonnett said she wanted people to understand sex trafficking did not only affect “the poor black kid on the West Side,” but rather that the impact was universal.

Cmdr. Michael Anton of the Cook County Sheriff’s Office agreed, saying, “It’s going on everywhere … [people] don’t realize how close it is to home. It’s happening right here.”

Bonnett also wished for the audience to understand the depth of suffering experienced by the trafficking victims.

Garcia had watched the play and found it “on point."

“Now I was getting paid for it, so why not?”

Garcia was sexually abused at the age of seven, and it continued for seven more years. Her childhood experiences made [sex trafficking] “so much easier.”

“I had already lost my virginity and had been exposed to things,” she said.“Now I was getting paid for it, so why not?”

Many pimps as well were once victims. According to a 2010 study on ex-pimps by Jody Raphael, a senior research fellow at DePaul University, and Brenda Myers-Powell, co-founder and executive director of The Dreamcatcher Foundation, the majority of respondents had experienced physical abuse and domestic violence growing up.

While interviewing pimps, Bonnett said she “always had to remember they were human beings,” that she was obtaining facts and to “not judge them on anything they did.”

Getting out there

Organizations such as the Chicago Dream Center (CDC) work to contact trafficking victims in Chicago and provide them with the necessary resources to start move beyond their abuse. Garcia was one of those victims.

“CDC showed up at my house … [they] picked me up … I had nothing to lose from going,” she said.

A two-year CDC program aimed at nurturing victims just emerging from the sex trade has graduated women just like Garcia, who is now a transitional living coordinator with the organization. She trains women in the program in job readiness and self-sufficiency, and helps them with housing.

Garcia attributes the biggest positive changes in her life to CDC.

- Graph shows percentage of respondents, all ex-pimps, who identified with the distinct household characteristics. Source: DePaul University College of Law

“[My biggest accomplishment has been] staying clean and sober for so long… almost 8 years,” she said. “That makes everything else an accomplishment. I’m a great mom because I’m clean and sober. I’m a great wife. I’m able to help the women.”

On the law enforcement level, Cook County Sheriff Tom Dart has prioritized human trafficking, Bieschke said. The sixth and latest National Day of Johns Arrests in July 2013, a sting operation organized by Dart’s office involving at least 20 law enforcement agencies nationwide, saw its highest number of arrests. However, the number of pimps arrested during each operation is consistently much lower than that of johns arrested.

“We can arrest a lot of pimps, but if the victim says [she] was not victimized then you really have no case,” Anton said. “We really rely on the victim[s] and their talking, [but] most of the time they don’t because of brainwashing [by their pimps]”.

Garcia described the pimp-trafficking victim relationship as a complex one. “It’s a love-hate relationship. It’s the love that you wanted for so long and did not have that will make it okay for you to be with the pimp.”

The issue of human trafficking has also impacted students. Judith Kim, a Northwestern University undergraduate, founded an organization dedicated to the fight against human trafficking.

“When I heard that slavery still existed it made me really angry,” the founder of Fighting For Freedom (F3) said. “It was infuriating … freedom is such a fundamental right that I couldn’t just sit still.”

F3 has brought in speakers from the Not For Sale campaign, and from the International Justice Mission, one of the leading international human rights agencies. Most recently, F3 hosted guest speaker Leif Coorlim, executive editor of the CNN Freedom Project, which raises awareness on human trafficking.

Kim thinks it is crucial for people not to see prostitutes as criminals — something many states, including Illinois, are starting to recognize with harsher penalties against johns and treatment for women caught in the trap.

“Many people we identify as prostitutes are in fact sex trafficking victims,” Kim said. “[They are] people who might need help.”

Woworuntu also highlights the lack of distinction between the two terms.

“People don’t know the difference between ‘prostitute’ and ‘victim’. They don’t know exactly what [we’ve] experienced. In the eyes of society … there’s no difference.”

Neighborhood efforts to combat the issue

For civilians to contribute to combating sex trafficking, efforts must start from home, Bonnett said.

“We as a community can do something about it through our own activism … just talking to your son or husband, or looking into [their] bedrooms and see what’s going on,” she said, including keeping an eye for pornography watching by youth and adults – particularly pornography featuring sex slavery.

Bonnett also encourages people to join the neighborhood watch and “see if that girl’s still on that corner.”

Still, Woworuntu stresses the difficulty of reaching out to victims, as many of them prefer remaining “in the shadows,” wanting to conceal their identities out of shame.

“Free from modern slavery”

After Woworuntu’s eventual escape from her traffickers in 2001, she was homeless for several months, faced with churches unwilling to help a so-called ‘sinner’, and unaccommodating law enforcement officers who constantly refused to believe her story.

One day, in her “hopeless and homeless condition,” she met a U.S. Navy officer who heard her story and brought her to the FBI. Woworuntu showed officers her diary, which she always had with her.

“I wrote everywhere I went. From those notes, they had to call a translator … I wasn’t lying. I took pens from customers’ rooms.”

Yet Woworuntu’s troubles still persisted.

Because she was a survivor during the early years of the Trafficking Victims Protection Act, human trafficking shelters such as CDC had yet to established.

“It was a struggle. No one gave me money, I had no clothes. My trafficker [had taken] my luggage, my passport … everything that I had,” she said.

Woworuntu was placed in a domestic violence shelter, where her post-traumatic stress disorder worsened.

“I became more paranoid, I became crazy.” Woworuntu increasingly depended on alcohol to calm herself, and even attempted suicide after suffering abuse from her second husband, a fellow Indonesian.

“When you’re in a relationship with someone you always forgive them,” she said. “[But] I couldn’t take it anymore after my second child was born. The violence was occurring more frequently and seriously. I decided to separate from him.”

Woworuntu managed to learn more about human trafficking and domestic violence, and it was through educating herself on these issues that she met two other survivors, Holly Smith and Ima Matul, who would become her mentors.

“Empowerment is crucial within the survivor community, because we’re weak,” she said.

Inspired by Smith and Matul, Woworuntu decided to use her ordeals to educate and raise awareness in the community—“I don’t want people to experience what I did. I want people free from this issue, free from modern slavery.”

- Source: Northeastern University

- This story produced by the Chicago Bureau.

Pingback: CHICAGO: National Hub for Human Trafficking | HUMAN RIGHTS SOCIETY

Pingback: Chicago Responds to Being Labeled a Trafficking Hub | Justice For Life