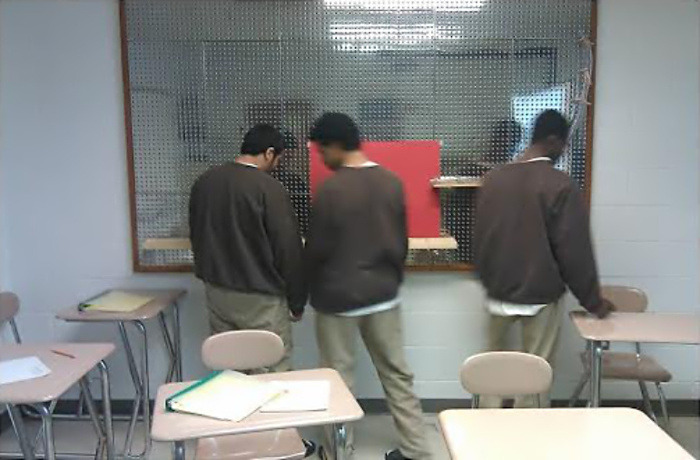

Photo Courtesy of the Massachusetts Department of Youth Services

Youths work on a math and science activity board at the Metro Youth Service Center, a juvenile detention facility in Boston. The Massachusetts Department of Youth Services banned punitive solitary confinement in 2009. To reduce the use of solitary confinement, experts say, it’s critical to keep youngsters occupied in engaging programs.

Behold the landscape of juvenile solitary confinement, and how quickly it can change.

When attorney Lydia Milnes began investigating the West Virginia Industrial Home for Youth in 2012 as preparation to file a lawsuit, she says, she encountered a boy who had been held in solitary confinement for six straight months as a 15-year-old.

The boy was held alone in a cell with a toilet, a bed and a desk-type structure for 23 hours a day and allowed out to take a shower and, if he had time, to sit in another cell from which he could watch a TV that was outside that cell.

During his stay in solitary at the juvenile detention center in Salem, W.Va., the boy never breathed fresh air because he wasn’t allowed outdoors, and the few hours’ education he received each week amounted to a teacher giving him workbooks and answering questions if he had any.

Milnes – an attorney with Mountain State Justice, a nonprofit law office serving low-income West Virginians that filed the lawsuit on behalf of two youths who had been held at IHY – said the boy told her he had been held in the “segregation unit” of the facility for disciplinary reasons about nine times. He also told her he had been placed in solitary as part of “administrative segregation” because staff deemed him too much trouble to deal with.

Milnes – an attorney with Mountain State Justice, a nonprofit law office serving low-income West Virginians that filed the lawsuit on behalf of two youths who had been held at IHY – said the boy told her he had been held in the “segregation unit” of the facility for disciplinary reasons about nine times. He also told her he had been placed in solitary as part of “administrative segregation” because staff deemed him too much trouble to deal with.

Today, as a result of the lawsuit, IHS is no longer a juvenile detention center – it’s been shifted to adult corrections – and the West Virginia Division of Juvenile Services rarely relies on solitary confinement in its juvenile facilities. DJS resorts to punitive isolation only after an administrative hearing before an independent hearing officer with due process rights for the resident such as the right to present testimony, bring witnesses, challenge allegations and appeal the hearing officer’s decision.

That stands in sharp contrast to the pre-lawsuit days when correctional officers often were friends with hearing officers, who routinely rubber-stamped the correctional officers’ imposition of as many as 30 days of punitive solitary confinement, and youths often received longer administrative segregation.

The shift away from solitary and toward a more rehabilitation-oriented juvenile justice system in West Virginia came as a result of court orders and agreements between the plaintiffs and DJS.

What happened in West Virginia – a dramatic shift away from punitive solitary confinement in juvenile facilities – has been happening in a small but growing number of states across the country.

At least 10 jurisdictions have banned punitive solitary confinement, while others have placed less-restrictive limits on its use.

The trend comes at a time when critics are increasingly asserting that juvenile solitary confinement – sometimes for as long as 23 hours a day alone in a cell or room – is torture and can cause irreparable psychological and developmental harm to youngsters. (Read more about the issues with isolation in Gary Gately's earlier story Juvenile Solitary Confinement: Modern-Day 'Torture' in US)

Against that backdrop, states shifting away from isolation provide compelling evidence that solitary can, in fact, be banned or restricted without jeopardizing the security of facilities or endangering staff or juveniles housed in them.

In some other states, correctional administrators, other local juvenile justice authorities or correctional officers’ unions have opposed bans on punitive solitary confinement of juveniles, saying eliminating the practice could pose risks to staff, juveniles or the security of facilities. (Read more about extreme cases of solitary confinement HERE)

Until recently, Stephanie Bond, now the acting director of West Virginia’s Division of Juvenile Services, was among those who viewed solitary as a go-to tool to manage juveniles in correctional facilities.

“I’ve been doing this for 20 years, and using segregation as a sanction has been what we had done for almost 20 years,” Bond told JJIE. “That was just the way that West Virginia had done things and to our knowledge, the way that other states were doing things, and as I found out in communicating with the other states, they’ve done the same things for years as well. So I think this is a new movement” away from solitary confinement of juveniles.

Bond, who has been in the acting director’s job since February 2013, said DJS conducted research on solitary and worked with the Council of Juvenile Correctional Administrators, whose performance-based standards include ones for solitary confinement.

The agreements and orders stemming from the lawsuit forced DJS to undertake changes quickly, and the transition away from routine use of solitary has been an adjustment.

“Our staff kind of felt like we were taking their main tool away from them and so we’re trying to equip them with better ways to manage the situation – going to an overall more therapeutic approach with the kids, trauma-based care,” Bond said.

Juvenile justice experts generally distinguish between punitive solitary confinement and timeout-type isolation used when a youth is deemed out of control or a threat to himself or others. Experts say such timeout confinement should last minutes or hours, not days or weeks, and the youth should be carefully supervised by staff.

Jurisdictions that have banned punitive solitary in juvenile facilities include Alaska, Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, Missouri, New York, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania and Washington, D.C.

Speaking of the growing number of jurisdictions abandoning punitive solitary, Laura Markle Downton, director of U.S. prisons policy and program for the National Religious Campaign Against Torture, told JJIE: “I think it’s accurate to say there is a groundswell, and there’s a groundswell around the country in which particularly people of conscience are asking very fundamental questions about what it means to have a justice system in which we subject individuals to conditions that lead to mental illness, that lead to suicide and … are given the label of rehabilitation.”

The Massachusetts Department of Youth Services banned punitive solitary confinement in 2009 after years of soul-searching and debate. The department began scrutinizing what it calls “room confinement” after two suicides in rooms in late 2003 and early 2004, both by hanging with bed sheets. (Neither of the victims was being held in solitary at the time of the suicides, and one of them was in a room with a sleeping roommate.)

But the suicides, combined with dozens of cases of kids harming themselves in juvenile facilities in the state, prompted DYS to review its room confinement policy, Peter Forbes, the commissioner of the department, told JJIE.

The transition to the current policy in which youth are kept in their rooms for a short period to cool off — it averaged 40 minutes in the last quarter of 2013 — came only after a considerable resistance from unionized DYS staff and rank-and-file managers in juvenile facilities, Forbes said.

“At the end of the day,” he said, “it was just like, ‘Guys, you got to get on the bus here, or you’ve got to find something else.’ With the union, it was pretty turbulent. We had a lot of assaults [after banning punitive solitary]. There was an unsettled period of time that I correlate with this particular policy change.”

But a reduction in the number of youths confined to DYS facilities helped the department make the transition, and there have been significant decreases in juvenile assaults on DYS staff each of the past four years, Forbes said.

Like other experts, Forbes says to avoid overuse of room confinement, it’s essential to keep juveniles occupied with engaging programming that lives up to the juvenile justice system’s rehabilitative mission.

“The goal for us is if school’s in session, we want the kids in their seats,” Forbes said. “If groups are being run, we want kids in their seats. If the kids are going to gym, we want kids in the gym. We don’t want them back on the unit on restriction or whatever. … It’s a rehabilitative focus in the agency, and we really understand that this is a really important shot every time we get a kid.”

He says all Massachusetts DYS facilities also have mental health workers on staff — another element experts call critical to minimizing the use of solitary confinement.

Alaska allows confinement only when a youth poses a threat to himself, others or the safety of a facility.

“We really do endeavor to keep the kids out of their cells as much as possible,” Matt Davidson, program coordinator for the Alaska Division of Juvenile Justice, told JJIE. “The major reason is we are trying to operate under restorative justice, and when kids are locked in their room, they’re not receiving the treatment that we’re trying to get them to receive.”

Alaska’s DJJ provides youth school five days a week and programs including ones focusing on aggression management, substance abuse and job training.

In Pennsylvania, youths cannot be confined more than four hours unless a medical professional examines the child and gives written order to continue the use of isolation.

Michael Pennington, director of the state’s Bureau of Juvenile Justice Services, told JJIE that type of confinement is used only as a “last resort” for safety and security and said it is used for as short a time as possible, with the youth observed every five minutes.

Staff at Pennsylvania juvenile facilities receive “de-escalation” training and annual refresher courses in de-escalation techniques.

“The bottom line for us is supervision is the key when you look at behavior management of kids,” Pennington said. “To isolate them when they’re having a difficult time behaviorally or mentally is a time of increased risk and self-harm, so isolating them without supervision for prolonged periods of time is certainly in my opinion not a good practice and not helpful for kids.

“We need to process these issues with kids and what’s going on, and obviously our kids come into the system with family issues, drug and alcohol issues, behavioral issues, mental health issues — you name it, it runs the gamut. So if kids are put in a position where they’re isolated without staff working with them or processing it, it increases the risk for kids of self-harm or other behaviors and it’s not going to turn out good.”

In Connecticut, confinement is used only for short periods when a youth needs to be removed from the general population temporarily.

Karl Alston, deputy director in charge of residential services in the Court Support Services Division of the Connecticut Judicial Branch, said staffers try to teach children how to manage stress effectively through anger-management, cognitive-behavior therapy and trauma-informed treatment, aimed at youths who have endured trauma.

“We don’t see our detention centers as prisons,” Alston told JJIE. “We’d rather see them as a school where we’ve become more therapeutic. We’ve brought in a lot of therapeutic programming. It’s just a different approach. We have to teach kids how to deal with their stresses, and once we do that and the kids understand it … then we start to see a difference in the behaviors and how to handle the behaviors.”

Alston knows many authorities at juvenile facilities elsewhere do not share that view.

“If you’re in the old culture, it’s easy to take a kid put them in a room and then there you have it, but what we encourage our staff to do is we encourage them to work with kids, we emphasize training on de-escalation, and we give them the tools to help them de-escalate,” Alston said. “And we have had resistance in the past with staff [but] once they get going and see the results and how it works and the instant change in a kid’s behavior, then they embrace it.”

Soon, many more juvenile detention facilities across the nation could begin moving away from punitive solitary confinement.

The Baltimore-based Annie E. Casey Foundation is drafting new standards for its more than 250 Juvenile Detention Alternatives Initiative sites in 39 states and the District of Columbia that call for an end to punitive solitary confinement of juveniles.

The new standards will certainly give impetus to the shift away from punitive solitary, given JDAI’s enormous influence as the nation’s most widely replicated juvenile justice reform effort.

But ending punitive solitary will pose huge challenges for juvenile facilities where it has long been the modus operandi.

“I think the most challenging thing is overcoming or changing the culture in the facility,” Mark Soler, executive director of the Washington-based Center for Children's Law and Policy, told JJIE. “Many, many facilities rely on long periods of room confinement for kids who break the rules. … There are certainly plenty of facilities that see room confinement as primary means of controlling misbehavior. So a kid breaks a rule, and they go to their room. They break a couple of rules, and they go to their rooms for a long time.”

Soler also acknowledged some unions’ opposition to bans on solitary — and said it is not surprising.

“They’re legitimately concerned about the safety of their members,” he said. “If one of our relatives were working in a facility like that, we wouldn’t want them to be at risk. We would want to make sure they were adequately trained and had other staff around and had good procedures in place.”

Soler lists a number of elements that need to be in place to safely make the shift away from punitive solitary confinement: training in verbal de-escalation techniques meant to defuse a situation; limiting solitary to short periods and situations that pose an immediate threat to a youth or others; ensuring adequate staffing levels, including mental health professionals; incorporating mental health staff when necessary in staff interventions; and relying on sound behavioral-management programs incorporating rewards, not just punishments many facilities rely on.

He said staff at juvenile facilities typically resort to the most restrictive responses to misbehavior such as solitary, restraints or pepper spray because they lack confidence to respond with less extreme approaches.

“This is about staff having confidence that they can handle the problems that come up when there are confrontations because unless they’re comfortable like that, they’re going to say, ‘We have to have these restrictive measures,’” Soler said.

Ned Loughran, executive director of the Council of Juvenile Correctional Administrators, based in Braintree, Mass., said juvenile facilities should collect, measure and analyze the use of solitary confinement.

“You can’t change what you don’t measure,” Loughran told JJIE. “So states that are being successful [in moving away from solitary] are the states that are measuring the use of isolation, then analyzing its use, developing facility-improvement plans to develop steps to reduce the use of isolation.”

To move away from solitary, Loughran said, it’s also critically important for staff at juvenile facilities to understand research in recent years on adolescent brain development that has found, among other things, juveniles’ brains are not fully developed and youths are more susceptible than adults to peer pressure, more impulsive, more likely to take risks, less likely to consider long-term consequences and more amenable to rehabilitation.

Paul DeMuro, a longtime juvenile justice expert who has served as a court-appointed monitor in child welfare and juvenile justice consent decrees in several states, said in a series of recommendations on ways to abolish punitive solitary for juveniles that all staff at a facility should have the same view of solitary.

He wrote that they must agree “the use of isolation causes more harm than good and, therefore, the use of and the duration of room confinement/isolation should be limited to the absolute minimum degree possible.”

In a paper published on an American Civil Liberties Union website in January, DeMuro also said not only youth, but also staff “can become institutionalized/conditioned to violent behavior… There is little doubt in my mind that much of the violence in secure juvenile institutions occurs because staff often depend on harsh and traditional institutional control methods (like the frequent use of isolation) that they have used over the years.”

DeMuro, who served as an expert witness for the plaintiffs in the West Virginia case, also pointed to the need for mental health treatment aimed at building on youths’ strengths instead of concentrating only on their weaknesses and said youths should be included in decisions about their lives.

He also stressed positive behavior management with concrete incentives for good behavior such as staying up later, more phone calls to home and more access to video games and TV.

Sanctions for major offenses such as assaulting staff, DeMuro wrote, should not last long, with the goal of getting the youth back into the program as soon as possible.

DeMuro told JJIE solitary makes youngsters “less trustful of the adults they deal with because any way you cut it, isolation is punitive and if you’re told by staff, ‘Well we’re really here to help you’ and you get thrown into isolation for 24 hours, 48 hours, it’s cognitive dissonance. How’s this program or this staff helping you?

“Isolation makes you more depressed, agitated, re-traumatized and more likely to self-harm yourself or commit suicide and finally, it makes you distrustful of the staff and their vowed intention to provide a caring environment for you.”

DISCLOSURE: Past and current financial supporters of the Juvenile Justice Information Exchange may be quoted or mentioned in our stories. They may also be the subjects of our stories.

Pingback: Growing Number of States Moving Away from Juvenile Solitary Confinement - The Good Men Project

Pingback: Seven Days in Solitary [3/23/2014] - Solitary Watch

Pingback: No Racial Differences Found in Effectiveness Of Psychotherapy for Depression | in-recovery.com

I am asking for help with my 9yr old son he is out of control he fights has anger outbursts steals from stores n hits his brothers n sisters

Please, please please…we need help for the boys in Harford Co, MD, who are charged as adults. They are all housed at the adult detention center. All are denied any type of education or any other program. I read these stories, and I am so outraged, because it is even worse for these boys! At best, they are locked down, alone in a cell, for 23 hours a day. During their one hour out of the cell, they are allowed (alone) to shower, make phone calls, and watch television. At worst, they are locked in isolation for 24 hours a day, sometimes without access to books, mail, visitors, or phone calls. They are not allowed bedding and must wear a hospital gown. One boy was held in isolation for 10 months, and then in segregation for the next 14 months. He was 16. These kids need our help now!