What are Dual Status Youth?

Dual status youth (also referred to as “crossover youth” or “multi-system youth”) refers to youth who come into contact with both the child welfare and juvenile justice systems, though they do not have to be concurrently involved.[1] A number of terms are used in reference to this population of youth to reflect distinctions between the different levels of system involvement.

- “Dually-identified youth” are currently involved with the juvenile justice system and are not currently in the child welfare system, though they have been involved with it in the past.[2]

- “Dually-involved youth” are concurrently involved with the child welfare and juvenile justice systems (could be through diversion, formal involvement, or a combination).[3]

- “Dually-adjudicated youth” are youth that have been concurrently adjudicated in both the child welfare and juvenile justice systems as dependent and delinquent.[4]

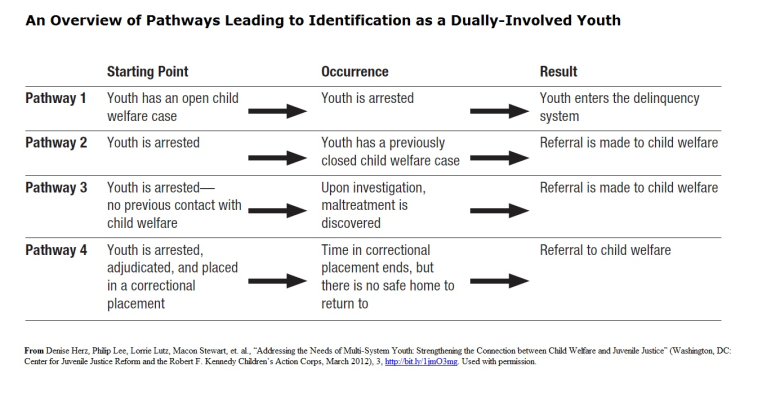

What are the Pathways to Dual Involvement?

Several pathways lead to dual involvement with the child welfare and juvenile justice system. Below is a chart providing an overview of the four main pathways:

How Prevalent are Dual Status Youth?

Depending on how broadly dual system involvement is defined, estimates of youth in the juvenile justice system with child welfare involvement is upwards of 50 percent.[5] In field work with several local jurisdictions across the country, the Robert F. Kennedy National Resource Center for Juvenile Justice has found that approximately two-thirds of the juvenile justice populations in these jurisdictions have had some level of contact with the child welfare system.[6]

Estimates vary depending on the methodological approach used, including which starting point is used (for example, measuring how many youth with child welfare backgrounds enter the juvenile justice system versus how many juvenile justice-involved youth have a child welfare background); what age groups are studied; which point in the juvenile justice system is studied (from juvenile intake to adjudication of delinquency, for example); and whether official data or self-report data are used.[7] Regardless of the methodological approach, however, some commonalities have been observed:

- The prevalence of dual system involvement may be greater among youth who have penetrated the juvenile justice system more deeply.

-

- For example, a 2004 study found that only one percent of youth receiving juvenile justice system diversion were dually involved, but seven percent of youth on probation were dually involved, and 42 percent of “probation placement” youth (meaning on probation supervision and in a group home or residential treatment placement) had an open child welfare case.[8]

- A 2009 study of youth exiting correctional centers between 1996 and 2003 found that 65 percent had been involved in the child welfare system prior to entering the correctional center.[9]

- When self-reports of maltreatment (abuse or neglect) are considered, the count of who has dual status involvement often increases.

-

- In a 2006 study of youth detained after an arrest between 1995 and 1998, 16.3 percent had a court record of maltreatment, but 82.7 percent of the youth self-reported maltreatment (with 9.4 percent reporting high levels of maltreatment).[10]

- Studies have found that a history of maltreatment is associated with an earlier entry into the juvenile justice system.[11]

-

- A study in King County, Washington, found that youth with a history of formal child welfare involvement began their delinquency careers earlier and were detained at an earlier age, more frequently, and for longer periods of time than youth without child welfare involvement.

- A Missouri study found that maltreatment was significantly associated with juvenile justice system referral at a younger age, an assault history, and a prior out-of-home placement.

Disparities

Both youth of color and females are disproportionally represented among dual status youth. A 2008 study found that disproportionality increased as both African-American and female youth moved from the child welfare to the delinquency system in Los Angeles.[12]

Racial and Ethnic Disparities

- For decades, youth of color have been overrepresented (and treated more harshly for the same behavior as their non-Hispanic white counterparts) at every stage of the delinquency process – from arrest, to secure detention, confinement, and transfer to the adult system. The causes are varied and have often proved resistant to change.[13]

- Likewise, African-American children are overrepresented in the child welfare system in every state[14] and are represented in child welfare and foster care placements nationally at a rate that is more than twice their representation in the population of children in the United States.[15]

- Studies examining maltreatment rates by race and ethnicity have found that African-American youth were more likely to have a court record of maltreatment even where the maltreatment rates were lower than those of white youth.[16] A 2011 report examining the link between child welfare and overrepresentation in the delinquency system concluded that the child welfare system was a significant pathway for African-American youth involved with the juvenile justice system.[17]

- While Latino youth are underrepresented nationally in the foster care system (though this may not be true in each local system), they are generally overrepresented in the juvenile justice system.[18]

- Not surprisingly, this pattern of disproportionality continues for dual-status youth. In fact, children of color are overrepresented among dual-status youth at similar or even greater rates than they are in the child welfare and delinquency systems.[19]

Gender Disparities

- Females are disproportionately represented in the dual-status youth population, where they comprise one-third to one-half of the cases, compared to the general delinquency population, where females generally comprise 20 to 25 percent of the cases.[20]

-

- While most offenses that lead to arrest are committed by boys, girls account for the majority of arrests for certain types of offenses, such as running away—59 percent—and prostitution and commercialized vice—69 percent. With 80percent of runaway girls reporting having been abused, it follows that runaways who are arrested are highly likely to be dual status youth.[21]

- Gender non-conforming girls are particularly at risk of juvenile justice system involvement after having contact with the child welfare system.[22]

Challenges Experienced by Dual-Status Youth

- Dual-status youth often struggle with a number of challenges, many of which are also common to youth in either the child welfare or the juvenile justice system, including educational and mental health problems, a higher incidence of drug use, and sexual abuse.[23]

- Additionally, dual status youth experience more “complex trauma” than youth in the general population -- meaning “exposure to multiple traumatic events, often of an invasive, interpersonal nature, with the potential to have more wide-ranging and long-term impact.”[24]

- Studies have also found that dual-status youth receive disparate treatment in the juvenile justice system, when compared to youth not involved in the child welfare system:[25]

- A 2009 study of detention decisions in New York City found that dual-status youth were more likely to be detained than youth not involved in the child welfare system.[26]

- A 2008 study in Los Angeles County found that in terms of dispositions, dual-status youth were more likely to receive placement in a group home or the more restrictive settings of juvenile justice ranches, camps, or placement with the state division of juvenile justice than youth who did not have an open child welfare case. Youth who were not dual status were more likely to be returned home on probation.[27]

- A 2011 report found that child welfare status more than doubled the risk of a child being formally processed in the juvenile justice system.[28]

How do Dual Status Youth Fare?

Several studies have found higher recidivism rates for dual-status youth than for youth with no child welfare involvement, sometimes by substantial amounts, and poorer outcomes in other areas of life as well.

- A 2011 study in Los Angeles County compared outcomes for youth involved in the child welfare system only, the probation system only, and those who were in both the child welfare and probation systems. Researchers found that the dual-status youth were more likely than either of the other two groups to have adult criminal justice system involvement.

- 64.2 percent recidivated within four years, compared to 47.6 percent for the probation-only youth and 25 percent for the foster care-only youth.

- Additionally, they were more likely to be on welfare and to access health, mental health, and substance abuse services, and were less likely to be consistently employed or to have high educational attainment.[29]

- A 2008 study in New York state found that being maltreated as a child was associated with increased risk of antisocial behavior as an adult and of being an adult perpetrator of abuse or neglect.[30]

- In a study that followed maltreated youth for a 25-year period, researchers found that maltreatment increased the likelihood of arrest as a youth by 59percent and as an adult by 28 percent.[31]

- A study of eight cohorts of youth exiting correctional systems between 1996 and 2003 found that youth with previous child welfare system involvement had a recidivism rate of 51 percent compared to 42 percent for youth with no child welfare system involvement.[32]

- A 2011 report in King County, Washington, found that 67 percent of the youth referred to the juvenile justice system in 2006 had some level of involvement or history with the county’s child welfare system. And dual status youth started their involvement with the juvenile justice system a year earlier than youth not involved in the child welfare system. After two years, the dual-status youth had a recidivism rate of 70 percent – over double that of non-child welfare-involved youth, who had a recidivism rate of 34 percent.[33]

Does Out of Home Placement Influence Future Involvement in the Juvenile Justice System?

When youth in the child welfare or juvenile justice system are placed outside of the home, the type of placement used can impact the likelihood of future involvement in the juvenile justice system.

Child Welfare Placements

- In comparing outcomes for youth placed in foster care versus youth placed in group homes, a 2008 study found that adolescents with at least one group home placement were at significantly increased risk of getting in trouble with the law – 20 percent versus 8 percent.[34] Note that 79 percent of these youth had their first arrest in a substitute care placement setting, and of these youth, 40 percent experienced their first arrest while in a group home.[35]

- A 2005 study of children in the child welfare system found that of the children placed into substitute care approximately 16 percent experienced at least one delinquency petition whereas this figure dropped to 7% for the children who were not removed from their family. [36]

- A 2002 study found that maltreated children placed outside the home were nearly twice as likely to experience arrest as an adult as those who stayed in the home. [37]

- Not only can out of home placement negatively influence youth outcomes, but they are expensive for the child welfare system. It is more cost-effective for the child welfare system to reduce out of home placements – specifically expensive group care.[38]

Juvenile Justice Placements

- Research and program evaluation suggests the need to reduce unnecessary out of home placements for youth in the juvenile justice system as well.[39]

- A 2012 study found that youth placed in detention prior to trial were more likely to be formally charged and adjudicated delinquent than youth who remained home.[40]

- Incarceration has been found to increase the rate of antisocial activity and raise the level of offending for some youth.[41]

How Do States Organize the Administration of Child Welfare and Juvenile Justice?

Coordination and collaboration between child welfare and juvenile justice systems is essential to increasing opportunities for prevention and improving outcomes for children and youth.[42] The degree to which states formally or informally collaborate varies greatly. A small number of states centralize the administration of child welfare and juvenile justice through a single state department or umbrella agency (seven states currently do this).[43] Other ways that states try to collaborate on dual-status cases include the following:[44]

- Data sharing[45]

Twenty-seven states use statewide information systems that allow for data to be shared consistently between systems (at least five states have single automated systems that house both child welfare and juvenile justice data).

- Committees or advisory groups

More common in decentralized states, these are multidisciplinary groups formed to improve systems integration for dual-status youth. Twenty-two states have such groups.

- Formal interagency memorandums of understanding (MOUs)

These are formal agreements between agencies to guide their systems integration efforts. Nineteen states have MOUs.

- Informal agency agreements

Eighteen states coordinate their work through informal arrangements based on historical practice and mutual trust.

- State and/or court rules

Approximately 15 states have statutes or court rules that encourage or mandate systems integration efforts. This is more common in decentralized states.

Regardless of whether the administration of juvenile justice and child welfare is centralized or decentralized, or whether any of the above agreements, rules, or groups exist, most jurisdictions must contend with common challenges that arise when multiple systems are working to address the needs of dual status youth and their families. These challenges typically relate to organizational culture -- the differences in missions, mandates, and philosophy between systems often working day-to-day in isolation from one another. Rarely do practitioners in child welfare and juvenile justice have a good understanding of what their counterparts in another agency do, or why. This frequently results in misunderstandings and friction between agencies and staff. Strategies for confronting these challenges are the focus of many of the reform trends.

Are Any Federal Initiatives Focused on Dual-Status Youth?

Several provisions of federal law support coordination and collaboration between the child welfare and juvenile justice systems. Note, however, that federal funding for such programs has been cut drastically in recent years, so localities may not be provided sufficient resources to implement many of these strategies.[46] Several provisions of federal law also address the use and maintenance of information relevant to the child welfare and juvenile justice systems and the sharing of that information, which is key to effective collaboration between the systems.

Two of the key pieces of federal legislation that encourage collaboration between the child welfare and juvenile justice systems are the following:

- Juvenile Justice Delinquency and Protection Act (JJDPA)[47]

In 2002, amendments were made to the JJDPA to encourage the coordination of the child welfare and juvenile justice systems. Specifically, under the formula grant program to the states, states must facilitate information-sharing in the following ways:[48]

-

- juvenile courts must have public child welfare records available to them when a youth is before them in juvenile court;

- policies and systems must be established to incorporate these child welfare records into the juvenile justice treatment plans for dispositional planning; and,

- states must provide assurances that youth in the juvenile justice system whose placements are funded by Title IV-E Foster Care receive the specified protections, including a case plan and case plan review.

- Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act (CAPTA)[49]

Amendments were added in 2003 that corresponded to the JJDPA amendments.[50] The CAPTA amendments included the following changes:

-

- Allowing states to use CAPTA grants to support and enhance collaboration between the child protection system and the juvenile justice system in order to improve delivery of services and continuity of treatment as children transition between systems.[51]

- A new requirement that states document in their state data reports how many children under the care of the state child protection system were transferred to the custody of the state juvenile justice system.[52]

Dual Status Youth Sections

|

|

|

|

|

Notes

[1]Janet K. Wiig and John A. Tuell with Jessica K. Heldman, “Guidebook for Juvenile Justice & Child Welfare System Coordination and Integration,” 3rd ed. (Washington, DC: Robert F. Kennedy Children’s Action Corps, 2013), xix; The level of contact could be informal (such as by having a voluntary case in the child welfare system or involvement in diversion from the juvenile justice system), or formal (such as having substantiated abuse or neglect findings in the child welfare system or being adjudicated delinquent in the juvenile justice system). (Hereafter, this document will be referred to as, “Guidebook.”) See also, Denise Herz, Philip Lee, Lorrie Lutz, Macon Stewart, et. al., “Addressing the Needs of Multi-System Youth: Strengthening the Connection between Child Welfare and Juvenile Justice” (Washington, DC: Center for Juvenile Justice Reform and the Robert F. Kennedy Children’s Action Corps, March 2012), 1-2. (Hereafter, this document will be referred to as, “Multisystem Youth.”)

[2] Wiig, et. al., “Guidebook,” xix.

[3] Wiig, et. al., “Guidebook,” xix.

[4] Wiig, et. al., “Guidebook,” xix.

[5] Douglas Thomas (ed.), “When Systems Collaborate: How Three Jurisdictions Improved Their Handling of Dual-Status Cases,” (Pittsburgh, PA: National Center for Juvenile Justice, April 2015): 3.

[6] Jessica Heldman, Associate Executive Director, Robert F. Kennedy National Resource Center for Juvenile Justice, Robert F. Kennedy Children’s Action Corps. Email communication, October 21, 2015.

[8] “Multisystem Youth,” 14; Gregory J. Halemba, Gene C. Siegel, Rachael D. Lord, and Susanna Zawacki, “Arizona Dual Jurisdiction Study,” (Pittsburgh, PA: National Center for Juvenile Justice, Nov. 30, 2004); 15, 19.

[11] Wiig, et. al., “Guidebook,” xiii.

[12] David Altschuler, Gary Stangler, Kent Berkley, Leonard Burton, “Supporting Youth in Transition to Adulthood: Lessons Learned from Child Welfare and Juvenile Justice” (Center for Juvenile Justice Reform and Jim Casey Youth Opportunities Initiative, April 2009): 25.

[13] Juvenile Justice Resource Hub, “Racial & Ethnic Fairness,” accessed Oct. 19, 2015; citing National Conference of State Legislatures, “Disproportionate Minority Contact,” 2, in Juvenile Justice Guidebook for Legislators (Denver, CO: Nov. 2011); James Bell and Laura John Ridolfi, “Adoration of the Question: Reflections on the Failure to Reduce Racial & Ethnic Disparities in the Juvenile Justice System,” ed. Shadi Rahimi, vol. 1 (San Francisco, CA: W. Haywood Burns Institute, Dec. 2008): 2-3; Mark Soler, “Missed Opportunity: Waiver, Race, Data, and Policy Reform,” Louisiana Law Review, 71 (2010): 23-24.

[14] Altschuler, et. al., “Supporting Youth in Transition to Adulthood,” 24.

[15] Models for Change, “Knowledge Brief: Is There a Link between Child Welfare and Disproportionate Minority Contact in Juvenile Justice?” (December 2011): 1.

[17] Models for Change, “Knowledge Brief,” 1.

[18] Center for Juvenile Justice Reform and Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago, “Racial and Ethnic Disparity and Disproportionality in Child Welfare and Juvenile Justice: A Compendium,” (January 2009): 13.

[20] “Multisystem Youth,” 16-17; A Los Angeles report found that 37 percent of youth in the juvenile justice system for the first time who were also involved in the child welfare system were female, although females only comprised 24 percent of first-time youth who were not involved in child welfare. Malika Saada Saar, Rebecca Epstein, Lindsay Rosenthal, Yasmin Vafa, “The Sexual Abuse to Prison Pipeline: The Girls’ Story,” (Human Rights Project for Girls, Georgetown Law Center on Poverty and Inequality, and Ms. Foundation for Women, 2015): 24.

[21]The Future of Children, “Girls and Boys in the Juvenile Justice System: Are There Differences That Warrant Policy Changes in the Juvenile Justice System?” (undated).

[22] Saar, et. al., “The Sexual Abuse to Prison Pipeline: The Girls’ Story,” 25.

[23] Brian Goldstein, “‘Crossover Youth’: The Intersection of Child Welfare & Juvenile Justice,” Juvenile Justice Information Exchange (JJIE), Nov. 15, 2012; “Multisystem Youth,” 17; Peter Leone and Lois Weinberg, “Addressing the Unmet Educational Needs of Children and Youth in the Juvenile Justice and Child Welfare Systems,” (Washington, DC: The Center for Juvenile Justice Reform, May 2010), 9.

[24] Thomas Grisso and Gina Vincent, “Trauma in Dual Status Youth: Putting Things in Perspective,” (Robert F. Kennedy Children’s Action Corps, RFK National Resource Center for Juvenile Justice, Jan. 13, 2015): 2.

[27] Joseph P. Rya and Denise C. Herz, “Crossover Youth and Juvenile Justice Processing in Los Angeles County” (Administrative Office of the Courts, Center for Families, Children & the Courts, December 2008): 6.

[28] Models for Change, “Knowledge Brief,” 3.

[29] Robert F. Kennedy National Resource Center for Juvenile Justice, Models for Change Resource Center Partnership, “From Conversation to Collaboration: How Child Welfare and Juvenile Justice Agencies Can Work Together to Improve Outcomes for Dual Status Youth” (May 8, 2014): 4; “Multisystem Youth,” 17.

[31] “Multisystem Youth,” 17-18.

[33] Robert F. Kennedy National Resource Center for Juvenile Justice, “From Conversation to Collaboration,” 4.

[34] Joseph P. Ryan, Jane Marie Marshall, Denise Herz, and Pedro M. Hernandez, “Juvenile Delinquency in Child Welfare: Investigating Group Home Effects,” Children and Youth Services Review, Vol. 30, Issue 9 (Sept. 2008): 7.

[35] Ryan, et. al., “Juvenile Delinquency in Child Welfare: Investigating Group Home Effects,” 8.

[36] Karen M. Kolivoski, Elizabeth Barnett, and Samuel Abbott, “The Crossover Youth Practice Model (CYPM), CYPM in Brief: Out-of-Home Placements and Crossover Youth” (Washington, DC: Center for Juvenile Justice Reform, McCourt School of Public Policy, Georgetown University, 2015): 5; citing Joseph P. Ryan & Mark F. Testa, “Child maltreatment and juvenile delinquency: Investigating the role of placement and placement instability,” Children and Youth Services Review, 27(3), 227-249.

[37] Kolivoski, et al., “The Crossover Youth Practice Model (CYPM),” 6.

[38] Kolivoski, et al., “The Crossover Youth Practice Model (CYPM),” 7.

[39] Kolivoski, et al., “The Crossover Youth Practice Model (CYPM),” 8.

[40] Kolivoski, et al., “The Crossover Youth Practice Model (CYPM),” 8.

[41] National Juvenile Justice Network, “Emerging Findings and Policy Implications from the Pathways to Desistance Study,” (Washington, DC: 2012); T. Loughran, et al., “Estimating a Dose-Response Relationship Between Length of Stay and Future Recidivism in Serious Juvenile Offenders,” Criminology, 47 (2009).

[42] Wiig, et. al., “Guidebook,” xvii.

[43] National Center for Juvenile Justice, Juvenile Justice Geography, Policy, Practice & Statistics (JJGPS), “Systems Integration,” accessed October 9, 2015. The creator of the site will be referred to hereafter as “JJGPS.”

[44] JJGPS, “Systems Integration,” accessed October 9, 2015.

[45] The data sharing referred to here encompasses state-level, individual record data sharing between child welfare and juvenile justice. The definition includes individual-level record sharing between court divisions for dependency and delinquency or sharing of social service records with probation or court divisions. Email from Hunter Hurst, Research Associate, National Center for Juvenile Justice to Melissa Goemann, National Juvenile Justice Network, Oct. 9, 2015.

[46] Jessica K. Heldman, “A Guide to Legal and Policy Analysis for Systems Integration,” (Washington, DC: Child Welfare League of America, 2006): 16-17.

[47] Juvenile Justice Delinquency and Prevention Act of 2002, 42 U.S.C. §§ 5601 et seq. (2002).

[48] “When Systems Collaborate,” p. 4; Wiig, et. al., “Guidebook,” xviii-ix; “Multi-System Youth,” 25.

[49] CAPTA Reauthorization Act of 2010, 42 U.S.C. § 5101 et seq.

[50] Note that CAPTA was also reauthorized in 2010 but these Code sections have not changed.

[51] CAPTA, 42 U.S.C. § 5106a[a][12] (2010); Wiig, et. al., “Guidebook,” xviii; “Multi-System Youth,” 25.

[52] CAPTA, 42 U.S.C. § 5106a[d][14] (2010); Wiig, et. al., “Guidebook,” xviii; “Multi-System Youth,” 25.