Art, Writing Shows What Young People Want From Police

|

A police officer kneels down face to face with a child.

“I’m sorry I stole,” the child cries.

“It’s OK. Just don’t do it again,” the officer replies.

Juvenile Justice Information Exchange (https://jjie.org/page/75/)

In late September, Torri was driving down the highway with her 11-year-old son Junior in the back seat when her phone started ringing.

It was the Hamilton County Sheriff’s deputy who worked at Junior’s middle school in Chattanooga, Tennessee. Deputy Arthur Richardson asked Torri where she was. She told him she was on the way to a family birthday dinner at LongHorn Steakhouse.

“He said, ‘Is Junior with you?’” Torri recalled.

Earlier that day, Junior had been accused by other students of making a threat against the school. When Torri had come to pick him up, she’d spoken with Richardson and with administrators, who’d told her he was allowed to return to class the next day. The principal had said she would carry out an investigation then. ProPublica and WPLN are using a nickname for Junior and not including Torri’s last name at the family’s request, to prevent him from being identifiable.

When Richardson called her in the car, Torri immediately felt uneasy. He didn’t say much before hanging up, and she thought about turning around to go home. But she kept driving. When they walked into the restaurant, Torri watched as Junior happily greeted his family.

Soon her phone rang again. It was the deputy. He said he was outside in the strip mall’s parking lot and needed to talk to Junior. Torri called Junior’s stepdad, Kevin Boyer, for extra support, putting him on speaker as she went outside to talk to Richardson. She left Junior with the family, wanting to protect her son for as long as she could ...

A police officer kneels down face to face with a child.

“I’m sorry I stole,” the child cries.

“It’s OK. Just don’t do it again,” the officer replies.

In the early morning hours of April 27, 2016, Kraig Lewis was up late studying for his statistics final. A graduate student at the University of Bridgeport in Connecticut with only nine credits left until completing his MBA, Lewis planned to go to law school next. At about 4 a.m., Bridgeport Police banged on his door.

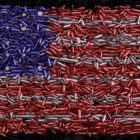

Guns are everywhere you think they’re not. Guns have been found on the floor of a movie theater and in the diaper aisle of a big box retailer. They aren’t just slid under a mattress at home or tossed up to the top shelf of a closet; they’re lying in a pile of leaves, or behind a toilet in an airport.

The mother left and two teens were alone in the house. It took the 13-year-old son 10 minutes to find the gun. It was loaded and in a bottom dresser drawer covered by one piece of clothing. It might as well have been on the fireplace mantle.

In recent years, juvenile justice practitioners, researchers and advocates have raised awareness of the harms of room confinement or isolation of youth in detention and residential facilities. Research and empirical knowledge teach us that the practice can negatively impact youth’s developing brains and emotional health, impair youth’s relationships with staff, limit youth’s access to important programming and treatment, and ultimately lead to unsafe facility environments.

Nataya Foss remembers being told that she would soon have to leave the shelter. She had been staying in one of Washington state’s few shelters for unaccompanied homeless minors, but because of restrictions that come with government funding, the shelter could house her for only three weeks. Her time was almost up.

On June 4, after 44 years in office, Broward County’s state attorney, Michael Satz, announced he’ll be stepping down. His departure could herald a sea change for the county’s criminal justice system, which has been marred by high-profile crimes and allegations of racially biased policing.

Best practices for state advisory groups as federal grant money has diminished is the focus of a new report from the Coalition for Juvenile Justice.