States should do more to ensure quality education for incarcerated youth, says a new report based on a 50-state survey.

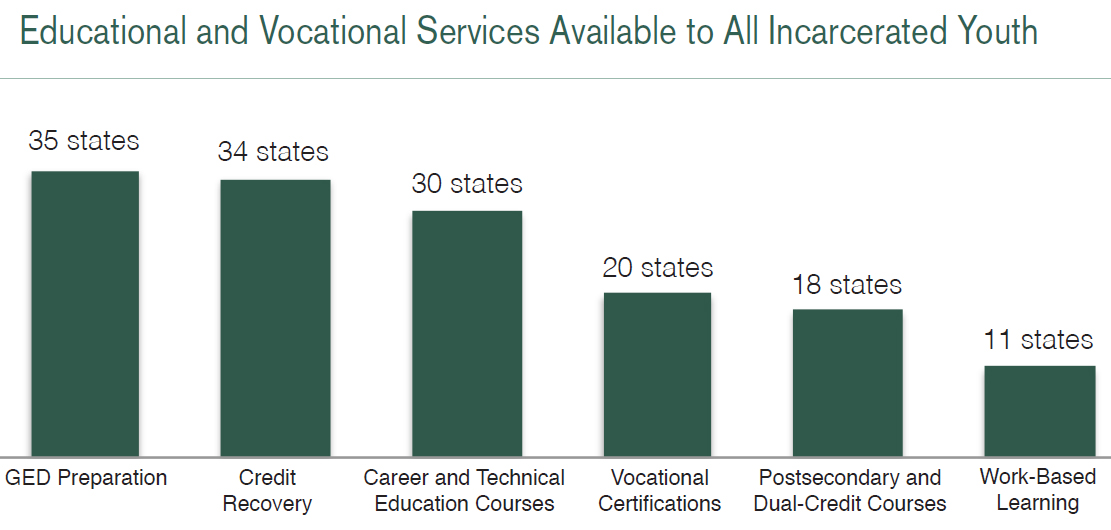

Many states are struggling to provide incarcerated youth with adequate educational and vocational services in areas such as curriculum, data collection and transitions back into the community, the Justice Center at The Council of State Governments said.

When youth have insufficient educational opportunities while incarcerated, it makes re-entry into the community difficult, said Nina Salomon, a senior policy analyst at the center and co-author of the report.

“Their chances of leading a productive life are better if they’re on track with education and employment,” she said.

The group surveyed all 50 states about the experiences of nearly 36,000 youth who are committed by a court disposition to a facility operated by the state, a local juvenile justice agency or a nonprofit or for-profit organization.

In the survey, eight states reported that incarcerated youth have access to the same education and vocational services as their peers in the community. The report urged states to improve those services, across all types of facilities.

[Related: Most States Still House Some Youth in Adult Prisons, Report Says]

“This standardization of services will ensure that the delivery of education is equitable and increase the likelihood that all incarcerated youth make progress toward college and career readiness upon release,” the report said.

The survey also found variation between the services in state and private facilities.

Almost all states collect data on high school credits and diplomas in public facilities and a majority track reading and math assessment data.

Less than a quarter of states collect similar data at privately run facilities, where 40 percent of youth in state custody are incarcerated.

The report noted that the types of facilities where youth are incarcerated have shifted over the years. In 1997, 34 percent of youth were in private facilities. In 2013, that share had grown to 41 percent. The balance between local and state facilities also shifted, with the local share growing from 12 to 20 percent of incarcerated youth.

The fragmentation can make it difficult for policymakers and state agencies to sort out which services are available, whether they are adequate and who is responsible for improving them, said the report.

Salomon said states historically have struggled with how to provide adequate education. But improving those systems is on reformers’ minds as the population of incarcerated youth decreases and more attention can be paid to their experiences and needs.

“The report shines a light and helps states assess where they are in providing educational and vocational services,” she said.

The report highlighted success stories from the states, such as a collaboration between the Oregon Youth Authority and the Oregon Department of Education to provide youth with a full range of services, and the creation of an accountability system for Florida educational programs run by the state juvenile justice agency.

The Robert F. Kennedy Juvenile Justice Collaborative, which often works at the intersection of juvenile justice and education, concurred with the findings.

“Youth involved in the juvenile justice system do not have sufficient access to quality education and vocational training, and … many state policies and practices make it difficult for young people to successfully enter appropriate community-based educational or vocational training programs upon reentry,” the group said in a statement.

More related articles:

States Should Mandate School-justice Partnership to End Violence Against Our Children

Schools Fail to Get It Right on Rap Music

Most States Still House Some Youth in Adult Prisons, Report Says