The Pew Charitable Trusts

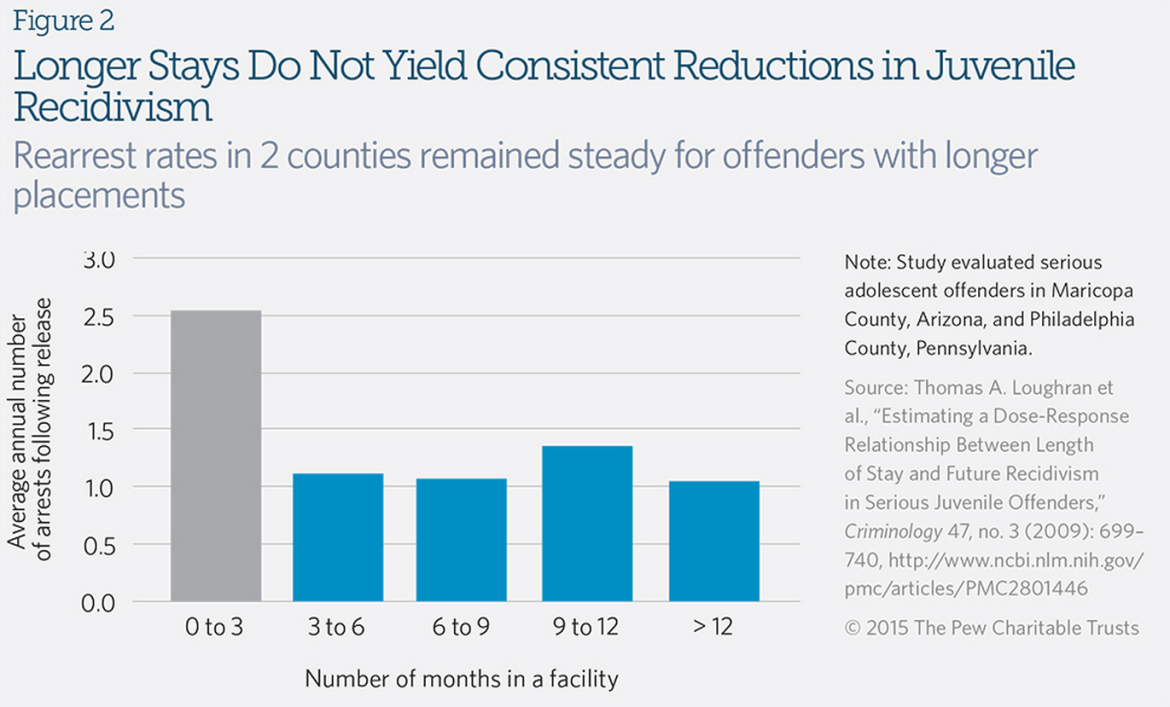

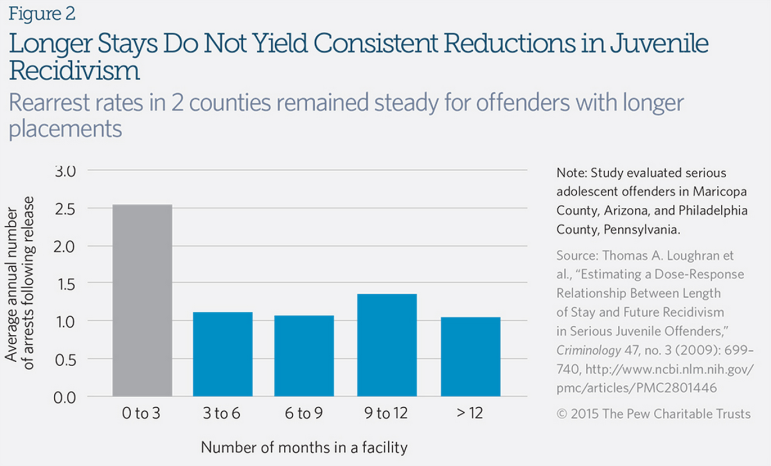

Infographic from the new analysis "Re-Examining Juvenile Incarceration" suggests longer stays do not necessarily reduce recidivism in juveniles.

What if you don’t lock them up?

With the annual cost of keeping a teen in juvenile detention topping $100,000 in many states, authorities increasingly are turning to community-based programs for youths who commit less serious crimes.

And states that have pursued alternatives to lockup are seeing fewer repeat offenders as well as saving money, according to a new analysis by the Pew Charitable Trusts.

“No one is saying we shouldn’t have any residential facilities,” said Jake Horowitz, the policy director for Pew’s Public Safety Performance Project. “I think there will always be some youth who pose a very significant public safety risk, and for their own safety and the safety of others, do need to be placed out of home.

“What the brief does show, however, is that by and large, for the vast majority of juvenile offenders, lengthy, out-of-home placement in residential facilities doesn’t produce better outcomes,” he said.

Pew reviewed studies of efforts in several states, including California, Ohio and Florida, to cut back on incarceration in the past several years.

The analysis doesn’t delve deeply into the reasons behind the results, but Horowitz said other studies suggest several reasons.

“Exposing particularly lower-risk, less serious offending youth to higher-risk, higher-seriousness youth creates a little bit of a ‘school of crime’ effect,” Horowitz said. “There’s clearly a case that by removing kids from their home and their communities, you are breaking some of the pro-social bonds that they have, whether with their family, friends, faith, schools or others. I think what we’ve seen from some of the studies is that placing them out of the home also doesn’t fix any of the bonds that were obviously broken.”

“Exposing particularly lower-risk, less serious offending youth to higher-risk, higher-seriousness youth creates a little bit of a ‘school of crime’ effect,” Horowitz said. “There’s clearly a case that by removing kids from their home and their communities, you are breaking some of the pro-social bonds that they have, whether with their family, friends, faith, schools or others. I think what we’ve seen from some of the studies is that placing them out of the home also doesn’t fix any of the bonds that were obviously broken.”

The worst bang for the buck appeared to be in Hawaii, where it costs nearly $200,000 to keep a teen in the state Youth Correctional Facility — and three out of four of those released between 2005 and 2007 were back in a youth facility or an adult prison within three years.

“What could you be doing with those dollars that could bring you a better public safety return?” Horowitz asked. “The state policymaker’s responsibility for both public safety and the public purse are coming together here.”

Shifting toward more of a community-based approach — probation coupled with family counseling, mental health services and education — will require state budgeters to put more money into those programs, Horowitz said. But even if you tripled the amount states currently spend on those services, “You could do that at a fraction of the cost of placing kids out of home.”

In 2014, Hawaii joined other states in cutting back on state commitment, reserving it only for teens found to have committed felonies; Kentucky, Georgia and Virginia have passed similar reforms. And researchers have found promising results from New York’s “Close to Home” program, which began in 2012.

“There’s been a realization by most states that trying to minimize the use of confinement for only those youth that are at highest risk of reoffending and for the most serious offenses is the wisest use of resources and also the best way to get better outcomes,” said Josh Weber, the juvenile justice program director at the Council of State Governments Justice Center.

Weber’s group was part of a study of the Texas program. It found that recidivism rates were lower for youths who were kept in a community-based program, and had lower felony recidivism rates in particular.

But the study didn’t find that simply shifting more resources into probation resulted in an overall reduction in recidivism: He said that shift requires not only more money but more attention to how that money is spent — “to ensure that services are prioritized for the highest-risk youth who need them,” he said.

All these changes have occurred against a backdrop of falling crime in general, Horowitz said. The number of teens arrested for violent crimes has been cut in half since the late 1990s. And though polling has found that the public still believes violent crime to be high, he said the polls show the public is willing to support reform measures.

“Essentially, voters are saying it doesn’t matter if a juvenile offender is in a facility for six or 12 or 18 months. What matters is that when they come out, they’re less likely to commit a new crime,” he said. “And what you see is overwhelming, bipartisan support for that kind of statement, as well as overwhelming support from crime-victim and law-enforcement households.”