When Linda Pace began her career as a public defender, things were different in DeKalb County, Ga. She recalls a system in the 1980s where the Department of Human Resources and local courts worked in tandem, with several court psychologists and special education teachers on staff. Young people in the juvenile justice system routinely received evaluations to pinpoint educational disabilities, and the local school systems regularly helped refer students to therapists. There were even more Medicaid services available to youth and families.

Katy McCarthy / JJIE

Read more from the series: Mental Health and the Juvenile Justice System: Progress, Problems and Paradoxes.

But with sweeping changes in the 1990s -- the era of the “super-predator, mythic nightmare,” she said -- Pace noticed a gradual decline in the quality of system services for juveniles. “The focus became criminal logic in the juvenile system, and the Department of Juvenile Justice (DJJ) and the court kind of changed their focus to meet the needs of the protection of the community,” she said. “And that became inconsistent sometimes, with the needs of children that have mental or behavioral disabilities.”

The DJJ, Pace believes, is no longer a viable entry point for youth requiring mental health services, with numerous “gate-keeping devices” in place ensuring that only the most absolutely critical kids get into residential treatment.

Currently, Georgia’s $307 million DJJ budget allocates only 13 percent towards community-based juvenile detention alternative programs, with 2 percent of annual funds going towards intensive, at-home therapeutic programs. Pace said that services are so scant in the state that she often advises the parents of children with severe mental health needs to relocate to other parts of the country.

“I have told parents [of children that have] diagnosed mental illness issues, such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder,” she said, “that they are going to be very frustrated with the community services that are available to them, and I have suggested that they move to states that have more resources and provide better services.”

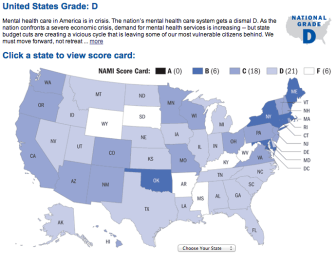

Grading the States / NAMI

Map of the U.S from NAMI's 'Grading the States 2009'

The de-emphasis of mental health funding in Georgia, however, is not an aberration across the United States. From 2009 until 2011, the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) reported that 31 states had enacted major mental health budget cuts. And in terms of overall mental health care quality, the national portrait is even grimmer; in a nationwide analysis conducted in 2009, NAMI scored 27 state systems -- among them, Florida, Illinois, Michigan and Texas -- with overall rankings of “D” or worse.

An Extremely Difficult Situation

Pace said the way youth are served has changed in large part due to the increasing number of young people that require services related to mental or behavioral disorders. As high as 70 percent of the children that pass through the local system, she said, have either a diagnosable behavioral or mental health condition. “In terms of those actually diagnosed,” she said, “it roughly comes out to be about 30 percent.”

As with many departments across the country, she said the economic downturn and budget cuts has led to a steep reduction in local juvenile services. “The Community Service Board does not serve as high of a percentage of the children with mental illnesses that they once did,” she said. “The private sector, under Medicaid, is expected to serve these children, and I think there’s an inadequate supply of community based services.”

She said she frequently speaks to parents who say they were told the court would place their children in residential treatment facilities or programs. However, Pace notes that the local juvenile courts themselves do not “traditionally” use screening tools for children referred on delinquency cases. For some parents, she likens the experience of trying to get their children into mental health treatment programs to slamming one’s head through a brick wall.

“It’s an extremely difficult situation for them,” she said. “They don’t understand why their child can’t be in a therapeutic setting and they would like to get help.”

The problem, Pace stated, was that most families seeking services “don’t know what help would look like, and they’re not sure what help would consist of.” Listing issues like Medicaid requirements, provider requirements and even staff turnover, she doesn’t believe obtaining services is any easier for families with children in the system that have behavioral disorders.

Shifting the Burden of Responsibility

Ed Harrison worked in Alabama’s criminal justice system for almost four decades. The 69-year-old recounts his days as a probation officer in the tiny town of Geneva, fondly.

Ed Harrison worked in Alabama’s criminal justice system for almost four decades. The 69-year-old recounts his days as a probation officer in the tiny town of Geneva, fondly.

“I enjoyed working with the kids and the parents,” he said. “Everyday was a new day.”

He recalled having to transport young people to diversion programs and facilities using his own vehicle and routinely swinging 60- and 70-hour work weeks.

In hindsight, however, he questions whether sending the young people to detention facilities resulted in any long-term benefits. “I don’t think it really helped after they got to that place in time,” he said.

Harrison said that roughly 35 to 40 percent of the children he worked with had behavioral disorders.

In the 1990s, Harrison said that school systems rarely turned to the juvenile justice system to address student behavioral problems. However, when a former juvenile judge in Geneva, about 100 miles south of Montgomery, established truancy and child abuse supervision programs during the midway point of the decade, he said schools began seeing the juvenile justice system as a means of “shifting the burden of responsibility” for students with mental or behavioral issues.

Before local young people were sent to facilities, he said, they were given numerous rehabilitation opportunities to avoid detention via probation and several diversion programs. “If that didn’t work, then [the system] put them in a diversion center, for 72 hours,” he said. “I didn’t like that as much, because they were always, on the first day, in solitary confinement.”

While Harrison said that young people had access to some services, most of their mental and behavioral health needs were not being adequately met. Of the personnel in the area at the time frame, he said “they weren’t so much doctors as they were counselors.”

Many of the children with mental health and behavioral needs that entered the juvenile justice system at the time, he believes, should never have been placed in detention. The effects, he said, are still reverberating for some of the individuals.

“If we would’ve saved just a few children,” he said, “we would’ve been better off.”

Many Do Not Belong in the System

Policy Research Associates / http://www.prainc.com/

Joseph J. Cocozza, Ph.D, Director of the National Center for Mental Health and Juvenile Justice.

According to Dr. Joseph Cocozza, Director of the National Center for Mental Health and Juvenile Justice (NCMHJJ) in Delmar, N.Y., young people involved in the nation’s juvenile justice system are three to four times likelier to have mental health disorders than the nation’s general youth population. (Learn more about the Center’s blueprint for designing mental health services for youth in the juvenile justice system here.)

“In general, all youth coming into contact with the justice system experience very high rates,” he said. “Clearly, there’s a relationship in general in terms of experiencing mental health disorders and level of income and class kinds of issues,” he added.

“Until very recently, there has been very little systematic attempt to identify youth involved in the juvenile justice system who have mental health disorders,” he stated. Cocozza said that researchers are just now arriving at a point where they can conduct longitudinal research to determine how many young people diagnosed with mental disorders actually receive treatment while in detention.

“The major question, honestly, is not what can we do to improve the juvenile justice system,“ he said. “The first priority is if these youth don’t belong in there, how do we link them to effective community-based behavioral services?”

Oftentimes, Cocozza said youth with mental health issues end up in the juvenile justice system, not because of a risk of criminal activity, but because they simply have not been able to access effective community services.

“Many of these youth do not belong in the juvenile justice system,” he said. “The juvenile justice system, traditionally and continuously, had not been established as a psychiatric center or major health provider.”

He said that there is currently a systematic movement away from group counseling, with a greater emphasis being placed on evidence-based practices. “A lot of the research literature indicate that the ones that are most effective tend to be community-based, family approaches, as reflected in things like Multi-Systemic Therapy (MST) and Functional Family Therapy (FFT),” he stated.

Cocozza said that instead of arresting young people when it is evident that a juvenile has mental health issues, law enforcement agencies and school officials should link them to mental health systems.

“There’s a strong emphasis on trends on keeping these youths out of the system,” he said. “Secondly, in terms of those who end up in the juvenile justice system, the emphasis at this point in terms of treatment is getting them access to evidence-based treatment and evidence-based services.”

In general, he said that fewer youth are entering into the deep end of the juvenile justice system, with states like Louisiana, Ohio and New York seeing drastic reductions in their juvenile populations. The youth that remain in the system, he said, are more likely to have severe mental health disorders, and require more clinical services while in detention.

“I think there’s an incredibly greater awareness of the fact that many of these youth have mental health issues,” he said. “There’s much more awareness that most of the youth also have co-occurring substance use issues, and we need to deal with them as integrative wholes.”

A Cruel Hoax?

Andrea Vargas / Juvenile In Justice

Bart Lubow, director of Annie E. Casey Foundation's Juvenile Justice Strategy Group

Bart Lubow, director of the Baltimore-based Annie E. Casey Foundation’s Juvenile Justice Strategy Group, has been instrumental in the development of the foundation’s Juvenile Detention Alternatives Initiative (JDAI), a project that has sought to reduce the number of confined and defined youth in the nation since 1992.

The JDAI, he said, is not necessarily focused on mental health. “It’s focused on getting people who work in the system to make smarter decisions in more timely ways and stop acting like bullies,” he said.

Lubow believes that while many young people in the juvenile justice system may have mental or behavioral disorders, reform efforts focused on reshaping confinement policies and practices would ultimately better serve such populations.

“The issue about whether or not a kid is held in detention prior to adjudication is not something that should vary as a function of their mental health,” Lubow said. “If you put a kid in a detention center because of poor mental health, that’s not a legal basis for detention, and being in detention is likely to worsen any clinical problems that a kid would have.”

He believes there has been a “tremendous tendency” in U.S. society to “criminalize” particular adolescent behaviors, including those that would generally be categorized as mental health issues. “Certainly, a very substantial percentage, for example, of school-based suspensions are imposed upon youth with special-ed problems, that the school system is not meeting its obligations to respond to,” he said. “And as a result, emotional or behavioral problems that ought to be dealt with and treated in school end up in a criminal referral to a delinquency court.”

However, Lubow adamantly believes that two other juvenile justice issues should take precedence over mental health concerns. He first cites the United States elevated rates of juvenile confinement compared to other countries, stating that a reliance on incarceration prevents systems from investing in earlier or more effective interventions. The second aspect he notes is the disproportionate number of minority young people who are involved in the national system. “Kids who come from families with resources and connections don’t end up in the system the way kids of color do,” he said. “They get treated in a second-class way, if not actually abused.”

Bethany Mollenkof / Los Angeles Times/MCT

New arrivals peep around the door at Camp Kenyon Scudder juvenile detention center in Santa Clarita. The camp is implementing a new health-screening program that is trying to address the problems females might face coming into LA County's juvenile justice system and flag girls who might need any additional help.

While Lubow said that there are significant numbers of youth involved in the nation’s juvenile justice system with mental health needs -- and that the system, as a whole, could do a much better job of responding to them -- he also believes the unmet mental health needs of kids in the delinquency system is a “safer issue” that draws attention away from what he considers more pressing systemic matters.

“Putting out a shingle that says ‘mental health services available here’ by what we currently know as the juvenile justice system is a cruel hoax,” he concluded. “And it all stems from this failure to deal with these two most obvious and pressing and defining problems in the system.”

A Medical Matter…Not A Criminal One

Denial and stigmatization, Pace said, is still a common problem, with many of the parents she speaks to refusing to believe their children have mental or behavioral disorders. Similarly, she said young people, most of whom are afraid of being “labeled” by their peers, are oftentimes reluctant to seek treatment.

On the national level, one of the biggest problems she observes is that, frequently, children with mental health disorders end up being placed in general treatment programs that do not meet or adequately address their specific needs. The impact on the juvenile justice system, she said, was apparent.

“If a child is receiving comprehensive and effective services that have been prepared to meet the individual child’s needs, and not the needs of the providers who need to fill a group,” she said, “then they are very unlikely to come back here.”

Pace said that she’s observed larger numbers of children with symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in the juvenile justice system. Treating the population, she said, is particularly challenging. Because many of the adolescents and teens experienced traumatic events when they were very young, she said that many of the same PTSD therapies routinely used on adult populations simply do not help young people reach “cognitive understandings” of their trauma and ways to manage it.

“As research goes on, we find out more and more about how the brain structures are actually affected by trauma and how this trauma resides and remains in those brain structures without anyone knowing it,” she said. As a result, Pace said that many young people with PTSD -- especially those that are undiagnosed -- may attempt to “subsume the pain” by explosive actions and drug and alcohol use.

For Pace, one of the absolute biggest problems she’s observed about the systemic treatment of youth with mental health and behavioral disorders is a “lack of compassion” from policymakers and the public.

“These kids get locked away for long periods of time,” she said. “Some kids are even found to be incompetent to stand trial [and] spend long periods of time in detention settings because nobody knows what to do with them.”

Young people with disorders, she said, frequently end up “languishing” in regional youth detention centers, without adequate treatment access or opportunities. “Even representatives from state agencies have a hard time getting access to services,” she added.

Improving mental health treatment for young people in the juvenile justice system, she believes, is contingent upon changing widely held perspectives about mental health and behavioral disorders. To change the viewpoint, Pace said, society needs to look at mental health treatment as a medical matter as opposed to a criminal justice issue.

“Despite the fact that people talk about mental health and behavioral disorders, they are still inclined to see these things as volitional on the part of the child,” she concluded. “I don’t think anybody would think that about a child that had diabetes.”