While investigating the “age-crime curve” literature, we discovered a crucial omission: decades of research associating adolescent age with more crime had failed to include the fact that adolescents and young adults — as a group and within every race and locale — suffer poverty rates double those of older adults.

While investigating the “age-crime curve” literature, we discovered a crucial omission: decades of research associating adolescent age with more crime had failed to include the fact that adolescents and young adults — as a group and within every race and locale — suffer poverty rates double those of older adults.

When we included poverty as a variable in arrest rates by age the age-crime curve disappeared, as did other supposed “adolescent risks.” Where 45-49 year-olds suffer the same high poverty levels as average 15-19 year-olds, middle-agers display “teenage” levels (or worse) of crime, gun violence, traffic crashes, etc. Conversely, where teens experience low poverty, they do not display “adolescent risks.”

Long-held beliefs that young age is a causal factor in crime and risky behavior appear to be a prejudice, like discredited past efforts to associate violence and race. Gun control is a critical example of how reasoned debate and policy are sabotaged by stigmas against youth. Round 1 of the latest debate was not about realities, but a recitation of myths about what leaders wanted gun violence to be: just a “youth” problem.

Last year, President Barack Obama blamed gun violence on “children” with “a void inside them.” He previously called for “collective anger” at “an entire generation of young men in our society who… shoot each other.” The only agreement between the president’s limited gun-control and the National Rifle Association’s weaponize-grownups campaigns was their misrepresentation of youth and schools as the epicenters of gun violence.

It’s one thing to grieve the murders of children; it’s another to demonize the nation’s youth as mass killers and schools as killing fields. In reality, children and teenaged youths commit 4 percent of the nation’s homicides and they suffer 3 percent of all gun deaths, according to the FBI and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The all-ages, all-venues nature of gun violence is obvious in recent rampages in homes, businesses, workplaces, shopping and entertainment centers, and streets by male suspects ages 15, 26, 27, 34, 35, 43, 62, 64, 65, and 68.

Just one-tenth of 1 percent of gun deaths occur in the nation’s 125,000 schools, according to CDC and National School Safety Center tabulations. The administration’s Child Maltreatment reports show 700 to 1,000 children and teenagers are murdered annually by violence in their homes, 30 to 50 times more than in schools. Young people murdered at home generate fleeting headlines (“Massachusetts father shoots children before killing himself,” “Connecticut teen fatally shot by dad called good kid,” “Father shot wife, children before killing himself”) but little attention from the president and other leaders.

Bad information breeds expedient, ineffective policy, as exemplified by the administration’s surviving gun initiatives and the president’s directive to the politically-attuned CDC to find that popular media and video games create a “culture of violence” among kids. The president praised local anti-violence initiatives in Minneapolis (where gun killings have declined modestly) while lamenting “youth violence” in Chicago (where deadly shootings have fallen much faster).

The irony is that young people show the most promising gun trends. Gun fatality rates have dropped by 50 percent among young Americans over the last two decades. Twenty years ago, Americans under age 25 comprised one-third of all gun fatalities; today, one-fifth. Meanwhile, those age 40-59 comprised one-fifth of gun deaths two decades ago; today, one-third.

Allowing for population changes, gun fatalities have been dropping four times faster among Americans under age 25 than among their middle-aged parent generation. Grownups are more likely to use a gun in the home to inflict violence on themselves and others than are their teenagers.

Why have generational gun risks reversed? The Violence Policy Center’s analysis of the General Social Survey suggests one reason: “the aging of the current-gun owning population — primarily white males — and a lack of interest in guns by youth” has reduced the percent of homes with guns from more than half before 1980 to just one-third today.

We are likely to see even more paranoia, irrationality, and firearms accumulation among dwindling gun-rights activists. But perhaps the next major gun tragedy will finally jar science-respecting leaders like the president into rejecting slogans and scapegoating, insisting on evidence-based policy discussion, and learning from young people’s promising trends.

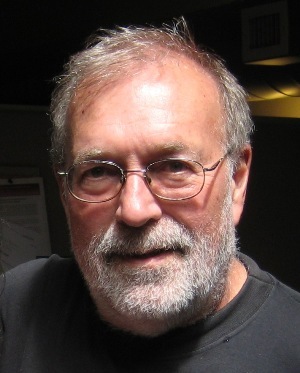

Mike Males is a senior research fellow at the Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice (CJCJ) in San Francisco.