TheFarm: Inside the Anchor Home for Boys from JJIE Multimedia on Vimeo.

The Baptist preacher Lester Roloff founded the Anchor Home for Boys to help troubled teenagers get their lives back on track. Nearly 50 years and three states later, the school that bears his name has transformed dramatically and escaped the allegations of abuse that once plagued its reputation. But many of its alumni are still haunted by questions.

Aaron Anderson’s dad had said they were going to the beach. Along with Aaron’s mother and younger brother, they were packed into the family car, careening past the sand and scrub of the Texas Gulf Coast on a spur-of-the-moment vacation that so far had included an amusement park in San Antonio and the Corpus Christi aquarium.

It was 1998, and 16-year-old Aaron was still coming out of a rebellious stage. He had been taking drugs and sneaking around with his girlfriend. His parents tried to home-school him. He tried to run away. His parents relented, allowing him to attend high school in Burleson, their rural town south of Fort Worth. That seemed to improve things. The family was getting along better and better. This vacation was the proof.

Which was why things didn’t add up when his father started driving away from the beach.

Before he thought to ask where they were going, they had arrived. It was a small set of buildings surrounded by farmland, just outside of Corpus Christi. “This is where you’re going to stay for the next year,” Aaron remembers his father saying. He remembers his brother crying and his mother remaining silent. He remembers an older man walking up and telling him to step out of the car.

When Aaron refused, the man left and returned with three more men. They yanked open the door and began pulling him out by force. “I was screaming at the top of my lungs,” Aaron recalled. “You put up a fight. You want somebody to hear.”

Aaron learned that he had been taken to the Anchor Home for Boys, which offered a year-long residential treatment program for teenage boys with various behavioral issues. His parents had heard about it from their pastor. At Anchor, Aaron would read his Bible every day and be kept under close watch. Hundreds of boys had gone through the school and spoken glowingly of having their path corrected in a safe, warm community.

As his parents and little brother drove away, Aaron was taken inside. “The rest of that day,” he said, “was pretty much non-stop beating.” The violence continued for weeks, Aaron said, until eventually he was put in charge of other boys and in turn oversaw harsh physical discipline.

When Aaron arrived at the Anchor Home, the institution had already been through a long and winding history of battles with Texas over allegations of abuse and a lack of oversight. After he left, the home would move to Montana and later to Missouri, where it currently operates.

Maurice Chammah / JJIE

Aaron Anderson

Throughout that history, there are allegations of abuse from some former students. But there are also denials from other students and from staff, who say those allegations are exaggerated and that for the most part the school provided an encouraging, positively transformative experience.

Eventually this back-and-forth gives way to something more complex. Many alumni describe conditions and practices that fall into a grey area between discipline and abuse and simply not feeling right. They can’t always decide whether what they experienced was wrong or illegal or valuable or just inexplicably strange. One said, “I'm glad somebody can hear me, because it's bananas." Another said, “It was crazy. It's hard to explain or to tell anybody.” Aaron Anderson said, “They have their own culture there. You never leave it.”

Hundreds of residential programs around the country — some religious, some secular — promise to improve the behavior of teenagers through strict discipline or ‘tough love.’ For the most part, these programs face little to no regulation from state and federal authorities, and that creates the conditions for abuse, which has been well-documented by journalists throughout the years.

But the lack of regulation also creates the conditions for all manner of practices, punishments and activities that are not abusive, not illegal and not “wrong” by any sort of official measurement but still may make some observers queasy and may have had negative psychological consequences on the teenagers who went through them. There’s no scoop here; just an endless stream of knotty questions. For many of the boys who went through Anchor, these questions — What really happened? Should it have happened? — are still unresolved.

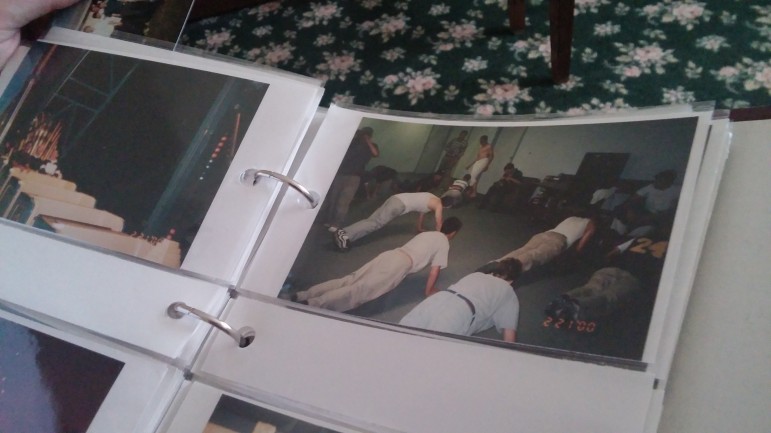

Personal Photo by Aaron Anderson of Anchor boys doing push-ups, 1999-2000

The Anchor Home for Boys was founded by the radio evangelist Lester Roloff in 1967, one of numerous homes set up by his ministry to help boys, girls, men and women struggling with problems ranging from adolescent disobedience to adult alcoholism. Until his death in 1982, Roloff battled with Texas over regulation of his youth homes. Outside activists accused the home of abusing its wards, while Roloff argued that strict Bible-inspired discipline was necessary to correct their wayward paths.

Roloff’s successor, Wiley Cameron, continued that battle, eventually moving some of the homes to Missouri before shutting them down. The homes reemerged under Cameron’s leadership in the late 1990s, when the Texas Legislature passed a bill allowing religious childcare institutions to be accredited by the Texas Association of Christian Child-Care Agencies, on whose board Cameron served.

When Aaron Anderson was dropped off by his parents in 1998, he became a member of the inaugural class of the revitalized Anchor Home in Corpus Christi. On his second day, he told me, he tried to escape and fell into a mud pit. He was taken back to the home and beaten. “My ribs hurt for a couple months after that,” he said. “Who knows if I cracked or bruised one. They never took me to a hospital.”

Over time, he learned to avoid getting hurt. The main way to do that was to stay totally silent. When he arrived at Anchor, Aaron said, he was placed on “verbal probation.” He was barred from speaking to anyone except for staff and a single “keeper,” and could only speak to them when instructed. Later students would use the term “guide student,” and the practice has lasted until today, defended by staff as a good way to break old self-destructive habits that the boys bring to Anchor.

Aaron told me that the punishments — for looking at others, for speaking to anyone outside of the approved structure — included hits and kicks from staff or from men at the Lighthouse home next door. He described being forced to kneel on rice for hours while weights — usually heavy books — were added to his outstretched arms. If he was put on “Red Shirt,” a special punishment designation whose numbers ranged from a few to as many as 20 other boys, he would have to run for hours on end, and be kicked if he fell down.

Over time he learned how to talk the talk. "If you pretend with a group of people long enough it feels real," he said. Less than a month after Aaron was allowed to talk to other students, he was put in charge of punishments. Instead of sitting in the classroom, where other kids had self-paced Christian workbooks, Aaron was out on the track, watching kids run endless laps and kicking them if they fell down from exhaustion.

His sole education was Bible memorization. If he succeeded in his memorizations, he might be treated to a John Wayne movie in the lunchroom or a short trip to a carnival with other “crew leaders.”

Fifteen years later, Aaron regretted how he had used his authority. “I get emotional, shaky when we talk about this,” he said. "I'm constantly questioning how I felt back then. Did part of me enjoy it?”

Maurice Chammah / JJIE

Dennis McElwrath at Anchor Academy in Vanduser, Mo.

As Aaron left in 2000, pressure was mounting on the school to open itself to scrutiny. News stories had been coming out about Anchor’s sister school, the Rebekah Home, where girls were telling stories of being whipped, beaten, bound with duck tape and locked in isolation cells with Roloff’s sermons blaring over speakers. In June 1999, Texas Child Protective Services issued findings of physical abuse and medical neglect at the Rebekah Home and banned Wiley Cameron’s wife, Fay Cameron, the head of the home, from working with juveniles in Texas ever again.

Day-to-day leadership of the Anchor Home was handed over to a 25-year-old named Dennis McElwrath, who decided to move the facility out of Texas. He reestablished the school as Anchor Academy and set up on two different sites in Montana before financial problems led him to relocate to Vanduser, a tiny cotton-ginning town in southern Missouri, where he operates it to this day.

McElwrath led a decisive break from the past, changing the minimum age to 16 and the maximum age to 24. Aside from a 2004 incident in which a staff member was fired after fondling a student, Anchor Academy escaped the allegations of abuse that had plagued its predecessor.

“Dedicated staff members are constantly mentoring and demonstrating Christian character as they work with the young men on an individual basis,” read the school’s new website. “A positive student culture allows new students to quickly adjust and be influenced by peers who have committed their heart and life to Jesus Christ.”

Maurice Chammah / JJIE

Front entrance to the Anchor Academy

Here are some of the punishments and general policies described by graduates of Anchor Academy during its years in Montana: spankings with a wooden paddle, hours of physical exercise in freezing weather with improper clothing, being prohibited from speaking to anyone other than a direct superior, spending eight hours on a Saturday scrubbing a single spot on the floor, eating peanut butter sandwiches for weeks at a time and having to carry them around in plastic sacks if you failed to eat them, having to hold a broom above your head while your feet were tied together, so that any movement required hopping around. Graduates described having to write hundreds and even thousands of repetitive lines of text by hand until their hands cramped. If you got behind, they said, you would be forced awake for 30 minutes every hour of the night to stand and write lines, which amounted to sleep deprivation.

“That place brainwashed, whether they intended to or not, an ideology, a dogma and a fear of physical and eternal punishment if you didn't comply,” said Michael Quinn, who attended from 2002 to 2004 in Havre, Mont. On the lingering effects of verbal probation, he said: “I ran out of things to talk to myself in my head about. I couldn't remember words. There was nothing up there in my head.” On the system of authority, he said, “I always to this day have trouble looking at people. I look at the ground.”

“Put your back against the wall and put your leg at a 90-degree angle and raise your arms,” he said, describing one punishment. “If you drop your leg I'd punch you. If you drop your arms I'd punch you. If you say no I'd punch you. I'd say that's torture. As a 16-year-old kid viewing this stuff, all I know is that it felt wrong.” When he described kids whose parents seemed like they might never come back, he broke down crying. “Nothing too terrible happened to me,” he said. “I played the game as much as I needed to.”

Other Anchor alumni say these punishments were wildly exaggerated by boys who were so undisciplined that getting up before noon could be spun into an act of torture. Daniel Minnick, who started in Corpus Christi in 1999 and then returned as a staff member in Montana intermittently until 2003, described Anchor as a “watered-down” version of the military, which he later joined. “We had it easy,” Daniel said. “I almost think that some of the folks that see it in a bad light never woke up to adult responsibilities.”

Was there violence? Daniel said, “Obviously you put those kind of youth in an environment with each other, there's going to be tension. One student is going to punch another student. Was that tolerated or perpetuated by staff members? No. But were there times I recall somebody got punched in the face? Sure. Boys will be boys.”

One theme that pervaded every interview for this story conducted about Anchor, particularly after its rebirth in the late 1990s, was the idea that the program fostered a very particular subculture that outsiders would find perplexing. One young man interrupted himself constantly to say, “It's so crazy. It's so crazy.” Several said that the school’s current head, Dennis McElwrath, or Brother Dennis as they call him, had a select group of boys come to his room each night. Those boys would rub his feet and serve as informants on what was happening outside of his gaze. “They tried to get me to rub feet,” Michael Quinn said. “They woke me up in the middle of the night.” He was sleepy and confused. “Then the kid came back and said, 'Never mind, go to bed.'”

Michael paused and then spoke, as if responding to this late-night silhouette of a boy from a decade before: “You're damn right! That's the weirdest thing ever!”

Maurice Chammah / JJIE

Jeffrey Barnes at home in Universal City, Texas

Anchor Academy and Anchor Baptist Church sit on one corner of the main intersection in Vanduser, Miss., the nicest buildings in a town of decaying wooden houses and vast cotton fields. Dennis McElwrath was standing on the front porch, chatting with a group of young men when I drove up on a recent Tuesday.

Over a dinner of goulash, string beans, and garlic bread, McElwrath gave me a broad overview of how he transformed the old Roloff’s Anchor Home into Anchor Academy.

He introduced financial literacy classes and set up accounts so the boys — he calls them “the fellas” — could get paid for work at the cotton gin and other projects, taking their savings when they left the home.

He said that the two major issues facing young men today are the fracturing of families and the emphasis on status — physical, social, financial — which makes them feel inadequate. He mentioned the high rate of teen suicide. “They get to a place where they don't want to face it anymore. We want a young man to come here and be safe, to know that they're not going to be made fun of or ridiculed.” He said that assigning guide students to newcomers and strictly managing who new students can talk to is part of the process of “putting the past in the past.” The guide students are supposed to exert “positive peer pressure” and the enforced silence keeps the new boys from “reinforcing old addictions.”

When we finally got to disciplinary policies, McElwrath was not defensive about the accusations of abuse we had both read on the Internet. He chose the analogy of traffic tickets, which if unpaid may lead to higher fines and then jail time. Small disciplinary infractions had minor penalties, he said, and the vast majority of the time that was enough.

Maurice Chammah / JJIE

Anchor Academy Classroom, Vanduser, Mo.

He said that the practices described by alumni I had spoken with were consequences given to only a tiny percentage of students who simply would not follow the rules, and that many of the most intransigent boys made a game of taunting staff members. He pointed to his bald spot and described an instance where one student had to run a single lap on the track as punishment and instead stood in place, ridiculing McElwrath as he got bitten by mosquitoes. "There are kids with unbelievable amounts of stubbornness,” McElwrath said. “There are times where you're worn to a complete frazzle. To them it's a game, to us it's like, 'Will anything get through to them?'” He said that in order to lower the number of boys like this, he increased the minimum age and started turning away kids whose problems were so severe that he felt the program could not help them.

“I’m not going to tell you there haven’t been mistakes made,” he said, giving credence to the criticism that he does not have extensive training in counseling. He mentioned Anchor Academy’s only brush with the law, in 2004, when an employee named Justin Peterson was charged with fondling a 15-year-old student and was promptly fired. “There is no substitute for experience,” McElwrath said. “If you do things the wrong way a few times you're apt to learn the best way to do it, and we're always open to change in the program overall. ... I'm not going to have doctor's degrees on the wall, but after 15 years we've been around the block enough times and know the heart of young people.”

After dinner, McElwrath gave me a tour of Anchor Academy, and I saw the perfectly-made cots, the cozy living spaces, the schoolroom with its individual desks and a school store with snacks you pay for with good grades and behavior, the clean and unadorned chapel, the vast stores of food, much of it fresh. All around me, boys were doing their evening chores: sweeping, cleaning plates from dinner, loading laundry by the armful. A few boys were on the phone with their parents. They nodded and smiled at McElwrath and I as we passed by.

McElwrath described the boys and the staff as a family with their own particular habits and quirks. "You may certainly see things that appear as strange, and you can ask me anything,” he said. As an example, he said I might see one boy having a friend work the knots in his back, since he had been to the doctor for these knots and that was the prescribed treatment.

Then, without prompting, McElwrath told me that he has a similar problem. “I have a lot of trouble with my feet; my feet will get so knotted up,” he said. “Sometimes guys will be a blessing and work on some of the knots in my foot.” The activities might seem strange to an outsider, he said, but “it's not uncommon when you live together. ... You’re with them all the time, it's like a family.”

The pervasiveness of abuse at residential homes for troubled teens has been well documented. In 2007, a series of deaths at residential programs for teens led to an investigation of teen deaths and “thousands of allegations of abuse” by the Government Accountability Office and a series of proposals for reforming the regulation of teen homes that since then have failed in Congress. In 2009, House Resolution 911, which would have created a national database of programs and increased access to abuse hotlines for teens, passed the House but did not make it through a Senate committee. In the years since, bills have not fared better. The Stop Child Abuse in Residential Programs for Teens Acts of 2011 and 2013 failed. The same bill was reintroduced this past February and has stalled in committee.

There are advocacy organizations trying to increase awareness of the issue. Two of the men I interviewed found one another through a group called HEAL, which aims, in the words of its coordinator, Angela Smith, to “improve laws so children and families are better informed and protected from fraud and abuse.” A group called Survivors of Institutional Abuse recently held their annual conference in New York City, where alumni and parents of schools like the Roloff homes traded stories.

But often there is little agreement about whether what occurred should be considered abuse. Just as there were men who still appear traumatized by what they witnessed and experienced, others remember a kind, peaceful environment. Feelings of where a line has been crossed — and where the law should get involved — are inconsistent, and might even change over time for a single person. Many of the boys simply accepted their experiences, but then, years later as adults, came to see what happened to them as wrong. Often it took finding someone else who had the same experience to validate the idea that what happened truly was wrong. If it was illegal, there is little recourse: In many cases around the country, staff at abusive residential programs have not been prosecuted due to the passing of statutes of limitations.

Still, just acknowledging what occurred can sometimes feel like its own small victory. About a decade after they left Anchor, in 2012, Sam found Michael living in Houston. They hadn’t spoken in years, but Sam drove down from his home in Dallas and they spent the day together. They found themselves coloring in each other’s sketchy memories of Anchor. “For a long time I started to believe I dreamed it,” Michael said. Sam “showed up and said, ‘Hey, this stuff really did happen.’ ... He made it real.”

This story was produced for the Juvenile Justice Information Exchange with support from the Fund for Investigative Journalism.

I was in the Montana location for 2 years, to sum it up; “Baptist slave labor brainwashing prison camp”. Happy they’re shut down! They have done so many terrible things. Abuse abuse & more abuse!

Pingback: Abuse Allegations Still Plague Religious Homes for Troubled Teens | CauseHub

I guess we have to “sugar-coat” our comments. Being made to do so, is similar to some of the milder crap that this place pulled on us. Bad place. Bad memories. Good friends.

How can you call handcuffing a person, and then giving them “licks” justifiable? How can you call having people kneel on boards until they memorized chapters from your Bible justifiable? How can you call having to eat lye soap, and not being able to eat ANYTHING for 2 days because of the damage to your mouth, justifiable punishment? I hope that EVERY person who committed these acts against children, and NUMEROUS more, are DEAD!!! I’d LOVE to see a few of those “staff members” now

When I was there in the very early 80’s, it was NOTHING like you are portraying it in this article. I don’t know any of the staff that you spoke with. Are you SURE that THEY were REALLY there at all?!? Clowns wanna’ say that no punishment was given unless it was due?!? And that it was OUR fault?!? Dude, I’m calling EVERY member of this alleged staff that you spoke to…”A Liar!”

I myself was in anchor, on the farm from 1982 to 1985. It sure sounds like these kids in the “reformed” Anchor had and still have it easy, from the time I spent in “ACHORTRAZ”

Was I abused, only mentally. Being at Anchor was a lot easier than living with my father! It’s the others that worried me. See, I knew how to play the game and played it quickly. I, personally witnessed crimes against children, too many to count. Or should we discus the 2 “students” who were sent home but never made home. I still call 1 mother yearly just to see if he EVER MADE IT HOME.

How am I to this day? I’m good.

Anchortraz boys, I’m here and looking for you! Y’all know who HOOF is, Find me!

Hey it’s Greg Slusher , I was there the same time you were . Get ahold of me on Facebook or call me 509-552-9631 it was hell. I remember get exiled to a Elton Missouri from Chopus Christi . I remember so much abuse … Brother Roberts and Brother Nick. Matt Maddox … trying to find out how to get ahold of him .

Hey it’s Greg Slusher , I was there the same time you were . Get ahold of me on Facebook or call me 509-552-9631 it was hell. I remember get exiled to a Belton Missouri from Chopus Christi . I remember so much abuse … Brother Roberts and Brother Nick. Matt Maddox … trying to find out how to get ahold of him .