Richard Ross / www.juvenile-in-justice.com

Alameda County Juvenile Court in San Leandro, Calif.juvenile-in-justice.com

This story is part of an ongoing series about juvenile indigent defense.

SAN LEANDRO, CALIF. — It’s mid-morning and the courts are crawling with clients, defenders, attorneys and families. There are no available interview rooms so juvenile public defender Dominique Pinkney and his teen client stand near a recycling bin. Pinkney uses it as a table.

“You may end up going in today,” Pinkney tells the client.

These are strange words to hear. In that moment, looking at this nice-looking, clean-cut kid and his mom, the idea of his spending two weeks in detention for not completing his community service seems more of an administrative detail than the reality of a kid spending two weeks in lock-up.

The 16-year-old client’s mother doesn’t speak English. She stands close to him, occasionally whispering hushed Spanish in his ear.

Pinkney shook his head. “This is a bad report,” he said.

…

The main job of juvenile public defenders is to act as the voice of children in the juvenile justice system. Public defenders for juveniles are required to understand not just the law — but the circumstances of their young clients and how to connect them with the most appropriate services. To the general public, even those involved in the juvenile court system in some way, the area of juvenile defense can seem shadowy and hidden. To provide insight into this world JJIE spent a day trailing juvenile public defender Pinkney at the Alameda County Juvenile Justice Center, atop a hill in this city in the East Bay, just south of Oakland.

The main job of juvenile public defenders is to act as the voice of children in the juvenile justice system. Public defenders for juveniles are required to understand not just the law — but the circumstances of their young clients and how to connect them with the most appropriate services. To the general public, even those involved in the juvenile court system in some way, the area of juvenile defense can seem shadowy and hidden. To provide insight into this world JJIE spent a day trailing juvenile public defender Pinkney at the Alameda County Juvenile Justice Center, atop a hill in this city in the East Bay, just south of Oakland.

Assistant public defender Dominique Pinkney arrives in the hallway outside the courtrooms every morning at 8:30 a.m. sharp, to meet with any clients who happen to come in early. At this hour the hallway is usually silent and empty. Benches line the walls, soon to be filled with anxious families waiting to be called into court. Coming in early allows Pinkney a little more time than permitted in the rushed moments between court sessions, when he convenes with a client for a few moments before going into the court with them.

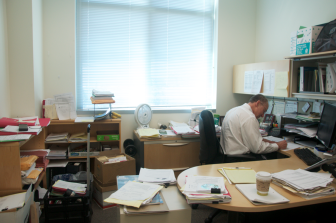

Katy McCarthy / JJIE

Assistant Public Defender Dominique Pinkney in his office at the Alameda County Juvenile Justice Center in San Leandro, Calif.

Pinkney has been a juvenile public defender for a little over a year, but spent almost three decades as a defender in the adult system before transitioning.

On this day, no one is around early. So Pinkney has a few moments to review his cases for the day. Sitting quietly at a table in a sparse interview room adjoining the court, he opens the red and green files of his clients and nods to himself as he pores over drug test results, completed community service reports and school records. Over the course of the morning, he and nine young clients will go in front of the judge.

The whirlwind starts promptly at 9 a.m. The halls, very recently devoid of anyone, are now swarming with parents, grandparents, melancholy teenagers and babies. Everything is a bustle.

…

The first client of the morning is sitting on the bench with his mom, dressed in a crisp green button-down shirt.

This is the first time the teen has been in trouble and he has unpaid restitution fees.

“It can be really hard for these poorer families to pay,” explains Pinkney.

In the legal system, restitution is when a judge orders the offender to give money or in-kind services for the harm or damage resulting from the offence.

Pinkney glances over his list of charges and intake report. Apparently, the teen was at a demonstration in downtown Oakland, when he and a group of other kids broke off from the group and started vandalizing cars.

Pinkney is hoping he will get informal supervision for six months, a more casual version of probation. Afterwards, his case would be dismissed. That is, however, if he pays restitution. If, after six months, he hasn’t paid, his supervision will be extended for another six months.

After the second extension, if he still hasn’t paid, the kid will go on standard probation.

…

In the 1967 ruling In re Gault, the United States Supreme Court ruled that youth had a constitutional right to counsel in delinquency proceedings -- essentially guaranteeing them many of the same due process rights as adults in criminal trials.

However, for this right to be relevant, young people need access to skilled representation.

According to the National Juvenile Defender Center (NJDC) in its National Juvenile Defense Standards that means creating, “an environment in which defenders have access to sufficient resources, including investigative and expert assistance, as well as specialized training, adequate and equitable compensation, and manageable caseloads.”

The reality for many juvenile indigent defense practitioners is that this is easier said than done.

Many young accused are not getting timely access to attorneys -- and when they do, the level of counsel they receive is frequently inadequate. A report by the NJDC raised serious concerns that “the interests of many young people in juvenile court are significantly compromised, and that many children are literally left defenseless.”

Pinkney, who spends many weekends in the office, is highly qualified and dedicated to the young people he represents. Multiple parents spoke highly of Pinkney. Several people called him “the best.” One mother stated that “he really fights for his clients.”

This is, however, not always the case with public defenders.

In many instances this is because of impossible workloads. The NJDC report found high caseloads to be “the single most important barrier to effective representation.” And that the ultimate impact of this on youth involved in the court was “devastating.”

“Children represented by overworked attorneys receive the clear impression that their attorneys do not care about them and are not going to make any effort on their behalf,” the report wrote.

Many of the same problems plague the system at a statewide level as well. Released in 2008, the Juvenile Delinquency Court Assessment (JDCA) took an in depth look at the California delinquency court system. Through surveys and focus groups conducted with delinquency court professionals and court users the report revealed significant issues within the system.

Many of the same problems plague the system at a statewide level as well. Released in 2008, the Juvenile Delinquency Court Assessment (JDCA) took an in depth look at the California delinquency court system. Through surveys and focus groups conducted with delinquency court professionals and court users the report revealed significant issues within the system.

The study cited a dearth of resources in many facets of the process -- from staffing to information regarding rehabilitation options. “Additional resources,” the authors wrote, “are needed to maintain caseloads at a reasonable level for judicial officers, attorneys, and probation officers.”

Furthermore, the study found that judicial officers, attorneys and probation officers who were surveyed expressed, “a general dissatisfaction with the sufficiency of information about, and the availability of, services for youth, most notably drug rehabilitation, mental health services, gender-specific services, and services for transitional-age youth.”

…

Richard Ross / www.juvenile-in-justice.com

The Alameda County Juvenile Justice Center in San Leandro, Calif., which houses the detention center and youth courts.juvenile-in-justice.com

Defender Pinkney states that on average he processes approximately 200 different clients per month. He is currently representing 194 teens.

To put that into perspective, The Connecticut Public Defender has set a soft cap of 300-400 juvenile cases per attorney, per year. In New York, the Legal Aid Society's Juvenile Rights Practice has a workload cap of up to 150 clients per attorney at any given time pursuant to a New York State Family Court Rule. For children charged with delinquency, the office averages between 35 and 40 clients per attorney at any given time.

Massachusetts caps the cases a public defender can take at 250 per year. Based on its weighting system, however, that translates to 165 delinquency cases, as each delinquency case is weighted at 1.5 times the amount of a “typical” court case. This is because, as the NJDC points out, caseloads describe only one thing — the number of “cases” being taken on. They suggest it might be more effective to look at “workload” standards, which incorporate the complexities of cases. In Oregon for example, the state bar standard’s state that “a full caseload for an attorney would be 6 felony level 11 cases in one year or at the other end of the spectrum, 600 drug diversion cases in one year.”

In his office, Pinkney gestures at a giant stack of client files in the corner, “The system is overwhelmed,” he sighs.

This year, Alameda County switched to a vertical representation system, in which clients are assigned to one public defender to represent them and work with them for the duration of their court involvement.

Prior to this, the Alameda County Courts operated on a horizontal system, where a client would be assigned to a different defender every time they came to court.

In this horizontal system, Pinkney explained, "Attorneys are assigned to a courtroom and handle all the matters that appear on that court room’s calendar with the exception of litigation (trials, suppression motions, restitution hearing, contested other hearings.”

Matters to be litigated tended to be assigned to the attorney who set the hearing.

“Thus that attorney does all the preparation for the hearing and the actual hearing. But it doesn’t always work out that way,” he told JJIE.

Local experts believe vertical representation is a significant positive change for the kids represented by the county.

“It’s the way it should be,” Sue Burrell, staff attorney at the San Francisco-based Youth Law Center, said. “Because these clients are young and it takes some time to develop a relationship with them, to get to a point where they trust you and for them to have the old system, to have a new person every time they come to court and start all over telling their story.”

However, nationally vertical representation is seen as the standard model.

David Shapiro, Gault Fellow at the National Juvenile Defender Center, states that, “The majority of jurisdictions already have “vertical representation,” but they call it what it is — representation. This sort of representation isn’t special — it’s the norm.”

…

Pinkney pauses for a moment considering the question -- why public defense work? -- before asking back, “If I’m going to put in 60 hours a week — who am I serving?”

“The idea of serving the poor – and every once in a while being able to put on a trial, pound a table … to fight for the disenfranchised, the folks everybody else dislikes.”

Pinkney grew up in an all black neighborhood in Vallejo., about 30 minutes north of where he now works in San Leandro. His mother was white; his father was a black American GI. Both of his parents were uneducated.

“All of my siblings are obviously black. I’m the only one of the four who grew up looking like mom. I know I look like an old white man today, but that’s my background,” he said.

Pinkney was born in France, and lived there until he was four when the family moved back to the states. Speaking no English, he struggled through grade school but ended up attending the University of California, Berkeley for his undergraduate degree.

Pinkney went on to be a public school teacher, working with kids in his old neighborhood. During a span of intense negotiations with the teachers union, the colleagues he was representing convinced him that his talent warranted a law school education.

After attending U.C. Hastings College of the Law in San Francisco, while clerking at the U.S Magistrate and planning on going into labor law, Pinkney had an informative experience that would change the course of his career. Most of the time in the Magistrate’s office he encountered nothing but corporate cases, where “the client was a piece of paper in their briefcase,” he remembered. However, for one month the magistrate saw criminal cases, and “the hallway would be full of grandmas, and everything you associate with the drama of people.”

Pinkney decided he wanted his clients to be people -- people he understood, people who needed someone to speak on their behalf.

“I’ve got a big mouth, and with my teaching background, I thought I could find a way to develop a persuasive presentation and liked the idea of representing poor folks, people from my community, fighting the power and making sure poor folks got treated well,” he said.

…

The second client of the morning arrived alone. She was in a green plaid flannel shirt, wearing orange nail polish. At 17, she was already recently married, wed in Reno, with both of their parents in tow to give consent. Someday, she wants to be a nurse.

“You’re one of the stars,” Pinkney told her. “But you know that.”

The client’s original charge was for battery. Pinkney calls her case a “wobbler” -- which essentially means that it could have gone either way in terms of being a felony or a misdemeanor. Happily, Pinkney says that the probation officer was so impressed with the client’s behavior that they suggested it be reduced from a felony to a misdemeanor.

As a juvenile public defender “there’s a social worker component … as well as a positive rehabilitation component seldom ever focused on in adult work,” said Pinkney.

“It feels good to get a young person back on track.”

…

In the early 2000s, reports of substandard conditions of confinement in the California Department of Juvenile Justice (formerly the California Youth Authority) began to circulate. In July 2004, in response to the reports and subsequent calls for reform, the San Francisco Public Defender’s Office and the Pacific Juvenile Defender Center (PJDC) convened the first ever statewide Youth Authority roundtable in which they collectively pledged to do their best to keep kids out of the system, or get them out if they were already incarcerated.

In the early 2000s, reports of substandard conditions of confinement in the California Department of Juvenile Justice (formerly the California Youth Authority) began to circulate. In July 2004, in response to the reports and subsequent calls for reform, the San Francisco Public Defender’s Office and the Pacific Juvenile Defender Center (PJDC) convened the first ever statewide Youth Authority roundtable in which they collectively pledged to do their best to keep kids out of the system, or get them out if they were already incarcerated.

“We just began to find our voice — to speak out, not just on behalf of individual lines but in relation to the whole juvenile justice system,” said Sue Burrell.

In a 2006 essay cataloguing California juvenile justice system reform, Burrel wrote, “The forces that have been set into motion have already had a dramatic impact on state level confinement for juveniles and the way we think about juvenile justice. At the peak of the “tough on crime” frenzy in 1996, the Youth Authority system housed 10,122 wards.”

Today, that number has significantly decreased. In 2012, the DJJ held fewer than 800 youths.

…

On a bench outside of the courtroom, a mother named Percelita struck up a conversation immediately. Bubbly, with a sparkly white flower tucked behind one ear and pearly teeth, Percelita works for a dentist and was missing work to be at court with her son. She only took four hours off this morning, and was hoping that she would be able to get back to work in time.

“What single parents can keep taking this kind of time off?” she said.

She was also disappointed by the attitudes of the public defenders she has encountered thus far.

“When I first met the P.D. assigned to my son’s case, he didn’t smile or even introduce himself … They don’t value our time. It’s very disheartening.”

According to the 2007 Juvenile Delinquency Court Assessment (JDCA) project Percelita’s sentiments are not uncommon. Many of the findings pointed to a need for better communication between professionals and court users.

Focus groups with youth on probation, their parents, victims and community members found that court users singled out wait times for hearings as an important area for court improvement.

“They would like shorter wait times in court, fewer continuances, and more consideration for their schedules and personal time constraints when scheduling cases,” the report said.

The assessment went on to find that court users felt that juvenile court was “complex and challenging to understand, particularly the language that professionals use to communicate with each other in court.”

This was Percelita and her son’s first time being involved in the court system. He got in trouble at school, but they believed everything was fine until they received a letter in the mail with a court date. On the phone with the public defender, she asked if there were any resources available to her to learn more about navigating the system.

“He said no,” she said.

…

Around 11:30 a.m., the client that met with Pinkney on the recycling bin emerges from the courtroom looking jubilant. He and his mother grin and exchange a few sentences in Spanish. The young man takes his hat off, smooths his hair, and puts his hat back on. They walk quickly down the hallway and out into the world.

The court day, which runs from 9 a.m. to 12 p.m. every day, is nearly over. Pinkney will spend the rest of the afternoon preparing for another set of sessions tomorrow. Another opportunity to keep a teenager at home and out of the system.

By 12 p.m., Pinkney is with his last client in court and the hallway is completely empty. A giant tiled mural depicts dark, ambiguous scenes: a girl crying, a figure running along a gray coast, a gloomy city scape of downtown Oakland.

The mural marches on down the hallway, like a slow but determined progression toward change. While it is not overly cheery or bright, it is honest, and there is something hopeful about it.

When he finally emerges from the courtroom, Pinkney doesn’t seem tired or overworked, just ready to keep fighting for his kids.

“I do feel there is something positive – although there are some negatives,” he said, “For the most part there is this positive energy and effort to move kids in the right direction.”

Pinkney recalled a client who was sent to a wilderness camp after being charged with a robbery. When he came home, he thanked the judge for sending him away.

“He self-corrected — whether it was at home or away or what, ultimately I don’t care, it was just a warm, cuddly experience. I shook his hand, and he and I both know he came a long way,” said Pinkney, “That kind of stuff happens in the juvenile system more often than we want to admit.”

Pingback: Woe Is Them Too | Simple Justice