NEW YORK — This isn’t your typical prison photography. But it isn’t supposed to be.

Instead of photos of prisons with chain-link fences and barbed wire, photographer Mark Strandquist produces images that give those locked up on the inside a view of the world outside. As part of his Windows from Prison workshop, Strandquist asks incarcerated individuals a simple question: “If you could have a window in your cell, what place from your past would it look out to?”

Then he and workshop participants set out to deliver the results.

On a wintry February day, about five dozen people gathered for the Virginia-based photographer’s first New York City installment of the project. Most of the workshop participants at the New School in Manhattan were strangers, having met only moments before. Excitement and anticipation filled the room as individuals split into smaller groups and each group received a manila envelope containing a letter.

On a wintry February day, about five dozen people gathered for the Virginia-based photographer’s first New York City installment of the project. Most of the workshop participants at the New School in Manhattan were strangers, having met only moments before. Excitement and anticipation filled the room as individuals split into smaller groups and each group received a manila envelope containing a letter.

“It would be awesome,” read one of the letters written by a woman incarcerated at Rikers Island, “if you can take a photo of the Nathan’s Hot Dog stand on the boardwalk of the beach and if somehow and someway get a picture of the beach area directly in front of the Nathan’s stand.” The letter writer explained that the location was important to her because “it was where my child and I had our first fun outing together. It was a beautiful moment in my life. Seeing my daughter playing in the sand and her awareness awakening.”

Strandquist first developed the Windows from Prison concept as an undergraduate at Virginia Commonwealth University in 2012. He conducted creative writing workshops at the Richmond City Jail, where he used the question as a writing prompt.

“Part of why I wanted to do this project was that the images I wanted to make weren’t in prison,” Strandquist said. “I wanted to make photos about incarceration with prisoners that had no cop cars or jail bars or execution chambers or any of these kinds of things.”

Instead, Strandquist considers the images a way of humanizing incarcerated individuals who have been cut off from the outside world.

He views mass incarceration as one of the leading human rights issues of today’s generation, he said. According to a 2014 report issued by the Bureau of Justice Statistics, the U.S. prison population has more than quadrupled in the last 35 years. In contrast, the total U.S. population has increased by only about 30 percent during the same time period. He sees his workshop as a way to raise awareness and create a broader discussion about the root causes of mass incarceration.

While Strandquist’s project began as a solo endeavor, it quickly expanded to include students at George Mason University and Duke Ellington High School in Washington, D.C. The students fulfilled requests received by incarcerated juveniles — teens creating images for other teens.

Strandquist had help in New York from Deborah Clearman, who has run a creative writing workshop for women at the Rose M. Singer Center on Rikers Island for the past four years. Clearman distributed the question as a writing prompt, much as Strandquist himself did when he created the project.

“Anything we can do to humanize the people who are incarcerated in the world, I think, is just really important,” Clearman said.

Brooke L. Williams

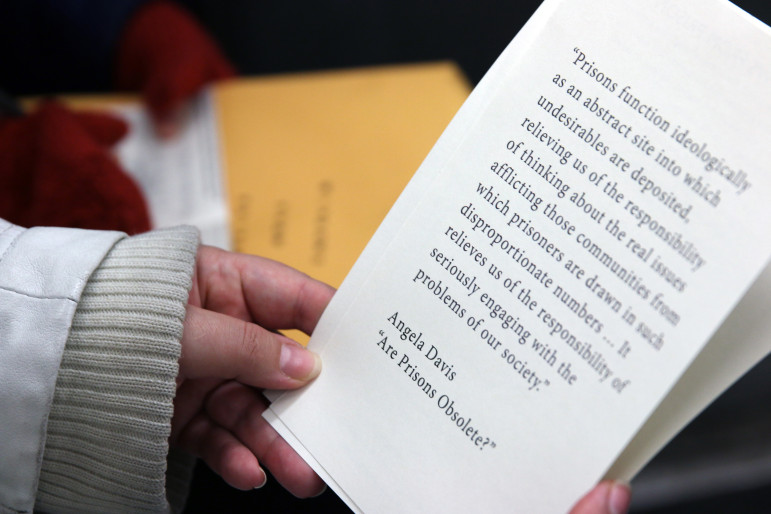

A participant at the Windows From Prison workshop looks through program material en route to Coney Island.

The women in Clearman’s workshop who chose to participate wrote letters detailing the location they wanted photographed, instructions for the photographer and, in some instances, a brief explanation of why the location was important to them. Requests were also received from a nearby juvenile detention facility. Strandquist’s only stipulation was that the locations be within the New York City metropolitan area.

But it is hard to put stipulations of any kind on the creative process. One woman requested a location in South Carolina. Another wrote a fantasy piece, Clearman said.

People who took part in the New York workshop included professional photographers, criminal justice reform advocates, the formerly incarcerated, students enrolled at the City University of New York Graduate School of Journalism and others simply interested in the project, including Clearman herself. Strandquist intentionally placed at least one member from each category into the smaller groups.

“As people went across the city, they were able to have these really powerful conversations and have these various experts within each group so that they became these kinds of mobile classrooms,” he said.

In order to facilitate that dialogue, Strandquist distributed booklets along with the photo requests. The booklets contained prompts of their own. Among the questions posed was this one: What do you think is the main cause of mass incarceration?

Participants shared their thoughts aloud with other group members and then recorded their responses in the booklets to document the conversations.

There were six photograph requests received from Clearman’s group of women at Rikers. One group went to the Bronx to photograph Yankee Stadium, another wound up in Central Park, yet another found its way to the Hudson River. Clearman’s group traveled to a neighborhood in Astoria, Queens.

Clearman said she understands the need for a fresh view inside a drab prison cell. In a book published earlier this year, which contains some of the work that has been produced in her Rikers workshop, Clearman described her first visit to the women’s facility.

“Windows showed a bleak courtyard with cracked cement, a basketball hoop, one dispirited tree,” she wrote.

Some workshop participants were concerned that rather than helping, the images would exacerbate the harsh realities of imprisonment. Rather than providing temporary relief, wouldn’t viewing a location that could not be visited simply make matters worse?

No, says Anisah Sabur, project associate for the Correctional Association’s Women In Prison Project. She was once incarcerated and chose to participate in the workshop on her only day off that week.

“When you’re looking at the same sad, dull environment every day, it kind of takes away from your positive thinking,” Sabur said.

“The funny thing is that most of the scenes that the women envisioned, like the beach or the park, were summertime scenes and the day of the photographing was freezing cold,” Clearman said. “Everything was frozen and covered in snow.”

But she insisted the women were pleased with the photos nonetheless. “Just to be acknowledged is so meaningful to them,” she said.

Indeed, there was a brutal chill in the air as one of the groups made its way to Coney Island that day. The Nathan’s Hot Dog stand was closed. The boardwalk was not crowded. There were patches of snow intermixed with beach sand.

But it was sunny and bright as the workshop participants captured the requested images. The sun’s rays reflected off the water, making the ocean shine like an array of brilliant diamonds. There were seagulls flying high in the blue sky above. It was a feeling not to be taken for granted.

That was a sentiment expressed again and again as the participants reconvened at the New School to share the images collected and their own reflections about the workshop experience. Strandquist recently worked on another installment of the project in Michigan and has plans to continue it in other areas throughout the year.

“My hope is that [the project] creates a really empathetic and humanistic stage to engage with these issues on a larger level,” he said.

Sabur described the experience as an emotional one.

“To work with a group of people who had no real experience with incarceration and no court involvement but had the same passion to really help somebody that was locked up, it just made me feel really good, you know,” Sabur said.

Clearman has either mailed or delivered the photos to all the women in her creative writing workshop. All, that is, but one.

In a way, the seats in Clearman’s creative writing workshop are like the seats in a game of musical chairs. Those who occupy them rotate often. Sometimes the women are in solitary and cannot come to the workshop on a particular day. Sometimes they are transferred to other facilities and stop coming altogether.

Then there are the ones like Bridget, who requested a photo of Yankee Stadium because she witnessed the old stadium being torn down and the new one being built. It reminded her of herself, she said.

Bridget has not yet received her photo, Clearman says, because she was recently released from Rikers Island. As Bridget wrote in her letter, “The old Bridget is no longer and the new Bridget has been built up shiny and new.”