["Bound by the Needle, the Dealer and the Drug" is part one of a three part series about heroin addiction. Bookmark this page for updates.]

["Bound by the Needle, the Dealer and the Drug" is part one of a three part series about heroin addiction. Bookmark this page for updates.]

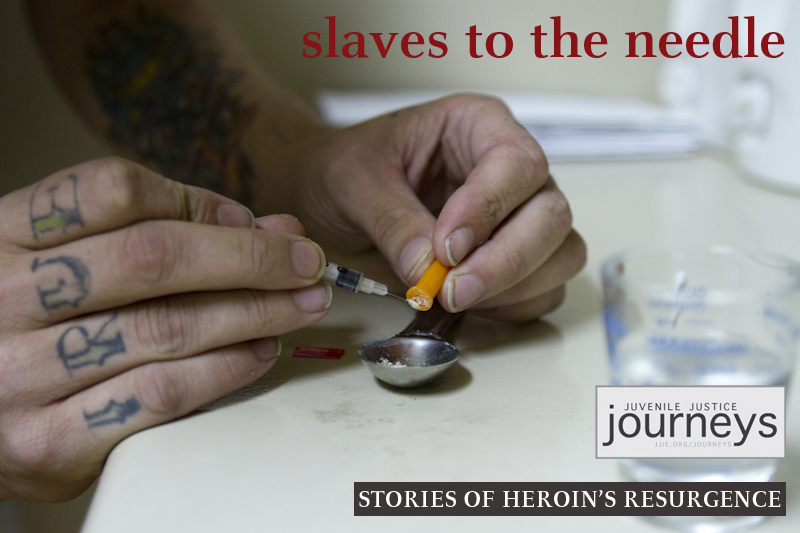

Editor's Note: The following story contains graphic language and images. It may not be suitable for all readers.

Chris Blum is laughing again, each breath a small wheeze followed by a noise that cuts through the surrounding sounds of the coffee shop patio. It’s full and rich, staccato and guttural; four beats long, the laugh of a man who sees the blessing in having anything to laugh about at all.

He’s a big guy, tall with a softness that comes with the newfound freedom to eat food without vomiting it back up again. Not long ago, Blum was a heroin addict. On this hot, sunny afternoon, Blum is sitting under an umbrella, dabbing perspiration away with a napkin and telling me about one of his jobs when he was an addict: a money collector for his dealer.

“I was a nice guy the first time,” he says, smiling. “The second time you didn’t see me coming.”

But then there’s the change, the dip from major to minor keys as he stops laughing. Sitting outside, I can’t see his eyes behind the dark sunglasses, but his smile quickly fades as he recounts one method of collecting a debt.

“The second time,” he continues, “you’d walk in the door and your girlfriend would be duct-taped and I’d have a gun to her head and a broomstick shoved up her ass.”

Blum pauses for a moment turning his face to mine, his last words hanging there awkwardly.

Chris Blum. Photo by Ryan Schill

Heroin addicts will do anything for a fix, Blum tells me, things they never thought they were capable of. For Blum, that meant helping his dealer with the dirty work.

“You’re not a very nice guy if you’re collecting money for drug dealers,” he said. “At that point, I did more drugs just to erase the memories of the crazy shit I was doing to people.”

“But,” Blum is quick to point out, his voice rising, “I’ve never killed anyone.” Then he pauses, thoughtful. “At least, they never told me they were dead.” He raises his hands as if to say, "What can you do?"

And then the first quick wheeze as Blum starts laughing again.

“You feel me?” William Parrish asks again, arching an eyebrow as he asks the question, to emphasize the point.

Parrish, in his 50s, lean and boyish despite his salt and pepper hair and bald pate, is sitting across from me at a large, round table in a conference room in the depths of the Gateway Center. Gateway, a drab, modern building set amid the classic judicial architecture of the downtown courthouses in Atlanta, houses a homeless shelter and rehabilitation services.

Parrish has been around, watching the ups and downs of opiate use over the decades. His experience came first as a user and now as an addiction counselor, the needle scars dotting his thin arms evidence of more than two decades of injecting heroin.

Long regarded as a hardcore drug plaguing inner cities, experts such as Parrish are saying heroin has found new life as a drug of convenience for suburban teenagers addicted to opiate-based prescription painkillers such as OxyContin. For those young addicts, heroin has grown beyond merely a threat; it’s a cheap, dangerous and highly-addictive alternative.

Recent news headlines point to an increase of heroin abuse among teens in the unlikeliest parts of the nation:

- “Heroin Use on the Rise in Northeast Wisconsin”

- “Heroin Overdose Deaths on the Rise” in Cincinnati, Ohio.

- “Heroin Deaths On The Rise” in Simi Valley, Calif.

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution recently reported how the city’s affluent northern suburbs were shocked by the death of three young men from heroin overdoses.

“The trajectory of it is eventually going to be of epidemic proportions,” Parrish said, looking at me squarely.

“You feel me?” he asks.

An intravenous drug user injecting heroin. Photo by Clay Duda.

Police are seeing a different picture of heroin, however. According to Agent Daniel Dillworth of the Marietta/Cobb/Smyrna (MCS) Narcotics and Intelligence Unit in Cobb County, Ga., heroin is not a significant problem. It’s the “least likely of the whole spectrum” of drugs, Dillworth said.

“If I see more than one arrest a month [for heroin possession] it would be unusual,” he said. “It’s way down there.”

Statistics bear that out. A White House Office of National Drug Control Policy report showed heroin use among high school kids nationally drop from 3.3 percent in 2003 to 1.3 percent in 2008.

So why the discrepancy? The demographics are shifting, Parrish said. Overall the number of heroin users may have gone down, but the users have changed from inner city youths to middle class and affluent suburban kids.

And it all begins when kids start raiding their parent’s medicine cabinet, he said. They know the names of the drugs. They know what to look for: among them OxyContin, Vicodin, Loratab, dilaudid and Percocet.

“And then,” he said, “they start experimenting with it. But little do they know you can become physically or psychologically dependent on it in a number of days. When they can’t get the prescription drugs there is only one other option: [they] got to go to the streets.”

The issue is availability, said Dr. Joe Gay, an expert in opiates and executive director of Health Recovery Services in Ohio.

“[In the Midwest] we’ve seen an influx of black tar heroin from Mexico,” Gay said. “The people dealing black tar decided what they wanted to do was to make money and not have gun fights. So they made it a point of marketing to areas without an established heroin trade.” They began marketing in the suburbs, Gay said. Dealers even began delivering to the buyer much like ordering a pizza.

Photo by Clay Duda

In the South, heroin is marketed differently. An Atlanta drug market analysis from 2010 prepared by the National Drug Intelligence Center says white, suburban youth are increasingly driving into the city, buying a few days worth of heroin and then heading back home where they sell some and use the rest.

Chris Davis, now 24, was one of those suburban youth. He first got hooked on opiate-based pain pills when he was in high school in suburban Atlanta.

“It progressed to snorting pain pills and it wasn’t enough so I moved on to heroin,” Davis said. “[Heroin] ruined everything.”

Chris Blum took a similar path to heroin addiction. He first began smoking marijuana and drinking when he was 16. But his addictions escalated.

Never say never, said Blum, now in his early 40s. “You think, ‘Oh I’m just drinking and smoking a doobie.’ But that’s how it starts.” Soon, he was snorting heroin with friends. It wasn’t long before he was shooting up intravenously.

"Cooking" heroin. Photo by Clay Duda

The simplest way to understand heroin addiction is to understand the brain. In one of the oldest parts of the brain — the midbrain — sits the reward center, the factory where dopamine, a hormone involved in motivation and reward, is produced and released into your body. The midbrain releases dopamine during sex or while eating an enjoyable meal, for example, and quite simply, it’s what makes you feel good. Heroin recreates that feeling by binding to receptors in your body that would normally bind with dopamine.

“It was like total relaxation — euphoria,” Chris Blum said of his first heroin high. “My eyes lit up. Everything got bigger and broader and pretty. I felt cool, you know?”

The high is so strong because heroin is able to break through the blood-brain barrier and mimic the effects of dopamine. But, noticing what appears to be extra dopamine, the brain cuts back on its own dopamine production. It stops making the hormone for itself and suddenly the body needs heroin to restore balance. To replace the missing dopamine, heroin addicts must continue to inject over and over. They become physically dependent even as the high becomes weaker and weaker.

The first high is the best, Blum said. “Then you chase that high. The more I did, the more I did.”

Blum said his addiction was “pretty much instant” and escalated from his first use to, “Man, I got to do that shit again.”

“Heroin — it calls your name, brother,” he told me. “You wake up and that is your first thought: If I don’t have any, how am I getting some?”

The life of a heroin addict can very quickly spiral out of control and dissolve into a cycle of getting high, followed by finding more drugs, followed by getting high. Without a consistent influx of heroin into the body, addicts begin experiencing intense, painful withdrawal symptoms, the National Institute on Drug Abuse said.

That’s where Chris Davis is now, constantly fighting off withdrawal.

“Within eight to ten hours of [using heroin] I start throwing up, having diarrhea, getting hot and cold chills, hurting all over,” Davis said. “I get real anxious and I just feel like there is another person inside of me that just wants to claw its way out and kill somebody.”

For Blum, heroin became the only thing he cared about. But the lethargy that followed the high robbed him of his ability to function normally. Everyday chores such as going to the grocery store became impossible.

“A normal person starts at zero and when they get high they get to 10,” Blum said. “An addict starts at negative 10 and needs to get high just to get to zero, to function.”

Chris Blum. Photo by Ryan Schill

Blum’s life was consumed with finding more drugs — or the money to buy more drugs. As Blum put it, “Next thing you know you’re in the back alley sucking some guy’s cock to get a fucking fix. I’ve seen it. I’ve seen guys go down that road.”

He lost everything: his well-paying job managing a large business, his family and eventually his home. He overdosed once — an experience that nearly killed him — and after a few years, he found himself alone in a dirty motel room wanting to die but unable to follow through with suicide.

“If [heroin] doesn’t put you in treatment or in jail, it’ll kill you,” Blum said. “That’s the only outcome … The last year: man, I prayed to die.”

Alone in his motel room, Blum hit rock bottom.

“All I knew was, I couldn’t stop,” he said. “I was hurting people. The nightmares didn’t stop. I was useless to my family.”

Shaking his head he told me that was the moment was when he knew he’d had enough.

“Fuck it, I’ll meet my maker,” he said he thought at the time.

But after a weekend of trying to overdose, Blum woke up before sunrise on Monday morning disgusted with himself.

“Now what?” he asked himself. “I can’t even fucking kill myself right.”

a sad but true story , having worked around addicts

you can look into their eyes and see their hooked