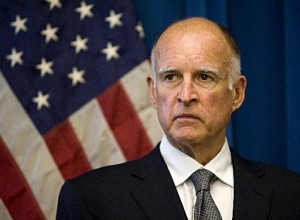

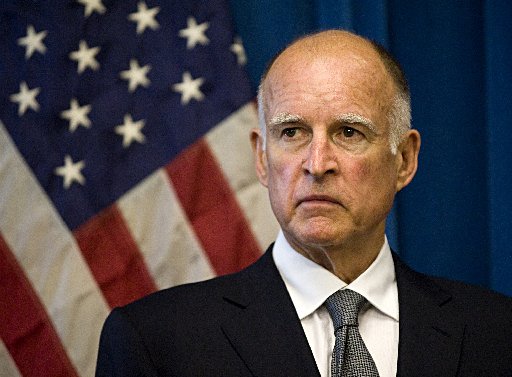

With the signature of Governor Jerry Brown, California, minus a few exceptions, joins the handful of states that guarantee an opportunity at parole to juveniles convicted of murder.

With the signature of Governor Jerry Brown, California, minus a few exceptions, joins the handful of states that guarantee an opportunity at parole to juveniles convicted of murder.

After serving 15 years, most of California’s roughly 300 so-called juvenile lifers will get a chance to ask for something they thought they would never see: a reduced sentence.

The new law allows judges to reduce a life-without-parole sentence to a 25-years-to-life sentence. That means the possibility of an appointment with the parole board.

“It’s very exciting, it’s huge,” said Dana Isaac, director of the Project to End Juvenile Life Without Parole at the University of San Francisco School of Law.

Offenders must show a resentencing judge their remorse and their work toward rehabilitation, under newly-signed Senate Bill 9.

At least seven states already prohibit juvenile life without parole, according to 2010 research by the Campaign for the Fair Sentencing of Youth, a nonprofit. They are Alaska, Colorado, Kansas, Kentucky, New Mexico and Oregon.

Jody Kent Lavy, director of the Campaign, called California’s reform “modest,” but added, “it represents a significant shift away from harsh sentencing policies that ignore the unique characteristics of children.”

Those unique characteristics are immaturity, a reduced ability to gauge risk and reward and other juvenile attributes that the U.S. Supreme Court has said in two recent decisions make young people less culpable than adults.

But Isaac added that she’s not out of a job. “It doesn’t get rid of all juvenile life without parole,” she said. “If you’re convicted of killing a cop or if you tortured your victim you’re not eligible.” Furthermore, a resentencing judge can still decline to reduce the sentence.

Offenders have a maximum three chances, five years apart, to ask for a new sentence.

Brown deliberated for the full 30 days allowed him before signing, announcing his agreement with the bill on the deadline of Sept. 30.

“There were a lot of compromises to get this passed,” said Michael Harris, senior attorney at the National Center for Youth Law, an Oakland, Ca.-based nonprofit that advocates for low-income children. Many prosecutors and victims’ rights groups battled it, while child advocates and mental health groups worked for it. Harris said if he were writing the bill, “I probably would make it a shorter period of time before the first opportunity” at resentencing and raise the number of chances for appeal.

Christine Ward was on the other side of the debate. “We’re disappointed,” said the executive director of the Crime Victims Action Alliance, a Sacramento nonprofit that aims to protect victims’ rights and public safety. “The juveniles that we’re talking about are juveniles that have committed the most heinous crimes,” she said, adding that many of them, if they had been adults, would have been eligible for the death penalty.

“We were comfortable with the way the law was working,” Ward explained. The courts had sentencing discretion, the defendant had the right to appeal, there were “checks and balances,” she said. Now, she opined, “It’s giving some leniency to juveniles who kill.”

But Isaac said, “California has a large percentage of kids who didn’t pull the trigger.” That is, offenders who were present at a murder, or participated at some crime that included a homicide, but did not actually kill.

In states that already have minimum sentences for homicide measured in years rather than “life,” the length varies. North Carolina’s is 25 years; Colorado’s is 40. The Pennsylvania legislature is debating 25 years for younger teens, 35 years for older teens.

Indeed, Pennsylvania and about half the states need new juvenile sentencing guidelines, because the U.S. Supreme Court has knocked down mandatory juvenile life over the past two years.

Isaac thinks other states might look at California’s language. “This could kind of show what can be passed to other states. If other people are thinking of putting forth bills, this could serve as a model of what could be successful,” she said.

Ward, on the other hand, predicted a legal challenge of some sort in California.

The sentence of juvenile life without parole technically remains on California’s books, said Adam Keigwin, who works in the office of bill sponsor state Sen. Leland Yee (D-San Francisco). But all future defendants who receive that sentence will also be able to appeal under SB 9.

This is a tough issue, but I think parole for juveniles is a good idea.