Maggie Lee / JJIE.org

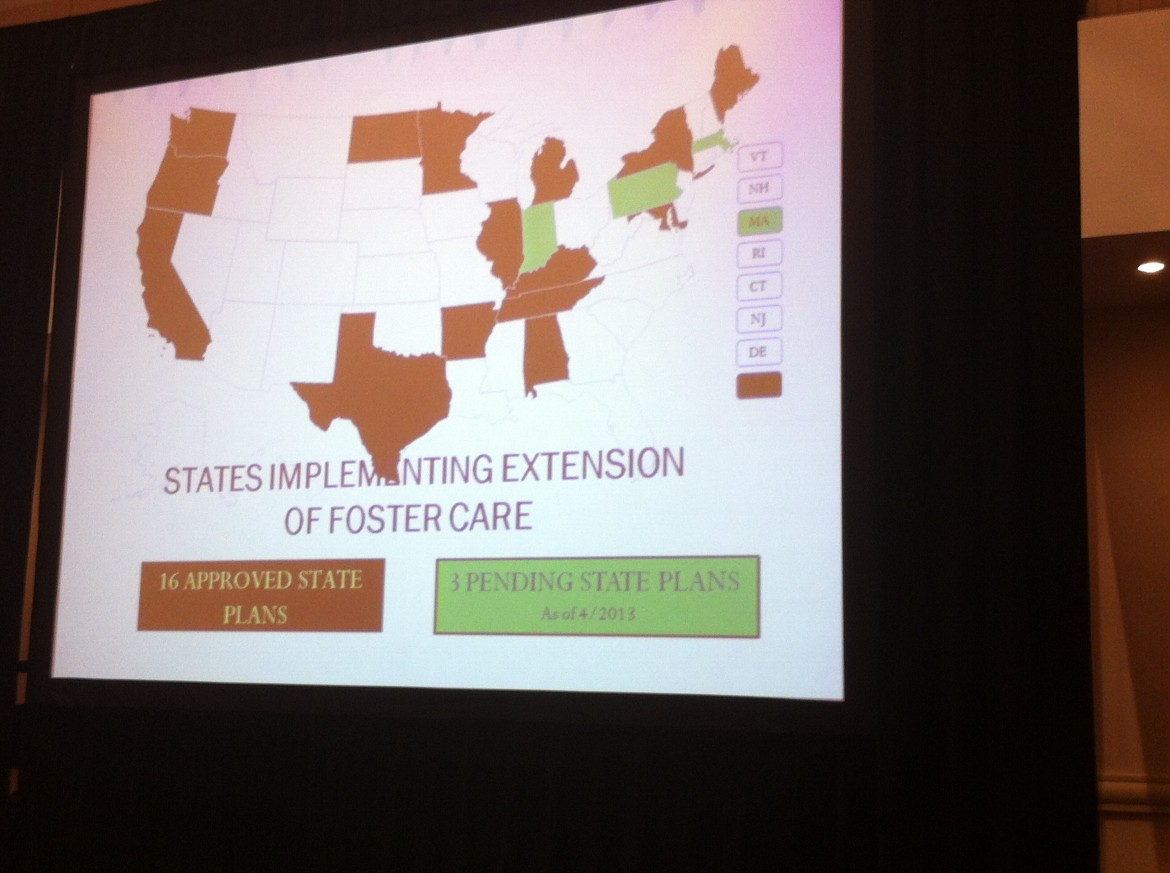

Sixteen states have enacted some sort of extended foster care, and three more have plans in the works, according to Christopher Wu, of the Center for Families, Children and the Courts at California’s Administrative Office of the Courts.

ATLANTA — Some 5,200 former California foster youth aged 18 to 21 are among the first in the nation to join a program meant to ease their transition to adulthood under a federal policy enacted five years ago and the evolving state law that implements it.

Some practitioners on the forefront of the philosophy say it’s a good idea, but offer ideas to other states thinking of giving it a try. For instance, build a coalition that crafts a thoughtful, flexible bill.

California is the “most important early adopter. … It has arguably the most expansive approach to this,” said Mark Courtney, a professor at the University of Chicago School of Social Service Administration who has studied post-foster care young adults in several states. He was speaking as part of a panel at the National Association of Counsel for Children’s annual conference on Aug. 26.

What California is rolling out, and continues to tweak now, is its Assembly Bill 12, signed in 2010, which extends foster care up to age 21. It’s meant to give young people time to work on things like finding a job, applying for school and financial aid, opening a bank account and finding a permanent connection to an adult supporter.

It can come with direct foster care payments to pay for independent living quarters like a dorm, apartment or room to rent.

Another option allows for support while living with biological family. According to Courtney’s research, young post-foster adults are more likely to live with biological family than foster family. One challenge to policy-makers, he said, is “to appreciate how heterogeneous this population is.”

Maggie Lee / JJIE.org

Christopher Wu said California’s extended foster care law is “emblematic” of bipartisan cooperation in the state Assembly on major policy questions over children in care over the last few years.

California’s law comes in the wake of the federal Fostering Connections Act of 2008.

The federal law does many things, but “one big one” was making it optional for states to expand the definition of child up to the age of 21, making states eligible for key title IV-E federal foster care funds, said Christopher Wu, of the Center for Families, Children and the Courts at California’s Administrative Office of the Courts.

Sixteen states have enacted some sort of extended foster care, and three more have plans in the works, according to Wu’s count.

When Miranda Sheffield was turning 18 and about to age out of California foster care, “it was either you have someplace to go, either transitional housing or the homeless shelter,” the now-27-year-old said. Her situation was “unique” because the woman she calls her “heart mom” took her in, she said. “The experience for my brother and everybody else was much more drastic. They didn’t have those options,” said Sheffield, who is now Fostering Success Connections Peer Advocate at the Children's Law Center of California in Los Angeles.

Peer advocates who are foster alumni are key because they’ve walked in clients’ shoes, said Leslie Heimov, also of the Children’s Law Center. That is, trained advocates who know the law, like Sheffield. “That’s a very important part of the program,” Heimov said.

Heimov started working on AB 12 long before the California Assembly considered it.

“It took us three years to write the first draft” of the legislation, she said.

By “us,” she meant the dozens of groups and individuals who consulted weekly on the bill for years: social workers, their union and management, juvenile justice officials, court-involved youth, foster families, relative caregivers, educators and more.

They wrangled over questions like eligibility for extended foster care. If a youth must be in education or training to qualify, what is “in school?” One class, a full load, or something in between? And for working young people, what if they lose a job through a layoff, no fault of their own, should they lose eligibility?

The result was a bill into which so many people put so much work, preparation, education and lobbying that it passed nearly unanimously.

“All of this is emblematic of the collaborative environment on major policy issues regarding children in care that we have enjoyed in California for the past few years,” said Wu, who was also part of the birth of AB 12.

“Not everybody thought it was a good idea,” said Heimov.

They were afraid foster connections would take the pressure off permanence and result in fewer kids reaching permanence by 18.

“It shouldn’t be a pass,” said Heimov. “It’s still something we talk about and we’re trying to balance.”

It’s a complicated act to watch, and is taking years, but may be very instructive for foster care policymakers.

California had to do this because they have done such a horrible job in helping foster children under the age of 18. If they did a better job with children under the age of 18 and getting them ready for adulthood instead of teaching entitlement they might not need AB12

Shouldn’t this article be in the business section?, like Forbes or Moneyweek?

California’s prison system, oops, strike that….California’s foster care is nothing to learn from, it’s a failure….anyone read the news these days?