In 1998, Laura Abasi was a Kenyan-born teenager from Queens who dreamed of a modeling career. As a high school junior, she got college pamphlets from leafy liberal arts schools and worked after school at a nearby market. She also got her first boyfriend, a charming 20-something who courted her with flowers and movie dates. Unfortunately, her trustworthy boyfriend turned out to be a pimp.

By the time Laura’s friends marched to pomp and circumstance, she was turning tricks on Manhattan street corners. And by the time Laura fled her violent pimp in 2004, she had 24 prostitution-related arrests on her record. Under New York State law, Laura was a criminal. It didn’t matter that she’d been inveigled into “the life” as a teenager, exploited for sex, and treated like property.

Today, however, it does matter.

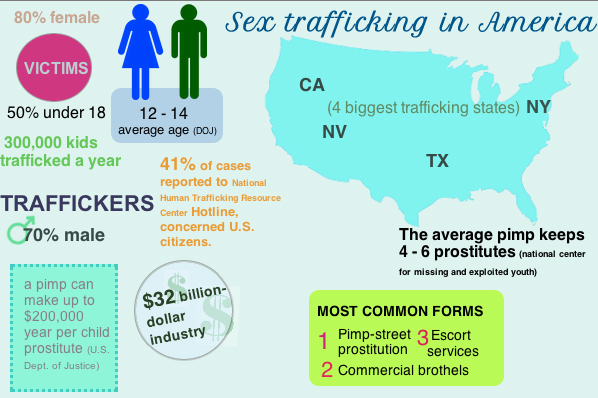

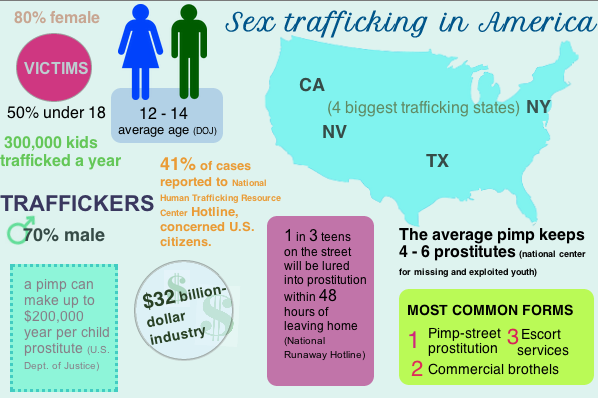

Sex trafficking is a global, national and local epidemic. As of 2013, according to Havocscope, a resource for Global Black Market Information, there are 20.9 million trafficking victims worldwide. Every hour, 34 people in America are forced into prostitution. And each year, almost 3,000 children in New York State, the country’s fourth-largest trafficking hub, get sucked into this version of modern-day slavery.

Since Laura left the life, New York State has created a new legal framework that treats many people charged with prostitution as victims rather than blameworthy criminals. New York criminalized sex trafficking in 2007 in a landmark anti-trafficking law. Simply put, sex trafficking is the exploitation of people for the purposes of sex.

Since Laura left the life, New York State has created a new legal framework that treats many people charged with prostitution as victims rather than blameworthy criminals. New York criminalized sex trafficking in 2007 in a landmark anti-trafficking law. Simply put, sex trafficking is the exploitation of people for the purposes of sex.

Subsequent anti-trafficking efforts have contributed to the shifting perspective that people who sell sex often deserve protection and social services, not criminal records and confinement. Recent victories include a 2014 law designating all minors engaged in prostitution as victims and a statewide system of specialized prostitution courts implemented last fall.

These achievements offer next generations of Lauras a better chance to leave trafficking with support and without criminal records. State anti-trafficking laws, however, are far from complete. Traffickers target vulnerable populations—young, poor, abused, homeless. A recent Covenant House study found that one in four homeless kids had either been trafficked or believed they’d have to trade sex to survive. To protect susceptible kids—and adults—from sexual exploitation, New York, among other states, must increase penalties for traffickers and johns. And, victims need more access to social services and greater protection from re-traumatizing prosecution to help restart their lives.

The Federal Model:

In 2000, Congress passed the “Trafficking Victims Protection Act,” the country’s first comprehensive anti-trafficking law. The TVPA enabled easier prosecution of sex and labor traffickers and provided protective and legal services to victims.

The TVPA modernized the Thirteenth Amendment’s framework for slavery. Beyond physical coercion and involuntary solitude, 21st-century traffickers exploit other people through psychological coercion and document withholding, among other tactics.

The TVPA also sparked awareness of trafficking as more than a scourge on developing nations. But federal law enforcement focused mostly on larger trafficking rings and couldn’t tackle the growing incidence of smaller-scale, intra-state trafficking.

New York Anti-Trafficking Laws:

In 2007, New York became the first state to pass a comprehensive anti-trafficking law. It criminalized two forms of human trafficking: sex trafficking and labor trafficking, defined as the use of force, fraud or coercion to traffic others for the purposes of sex, or labor or services.

The law characterized some people as trafficking victims, who, under previous laws, would have been prosecuted for prostitution. Victims became eligible for social services including health care, job training, shelter, therapy, immigration assistance, and general protection. The law, though monumental, had big gaps.

The following year, New York passed a Safe Harbor law to address one such gap: criminalizing sexually exploited kids. The anti-trafficking law permitted prosecution and detention of children who couldn’t legally consent to sex with adults. The Safe Harbor law classified sexually exploited youth under 15 as victims—entitled to services and protected from criminal charges.

Together, the 2007 law and the Safe Harbor law broke ground, but they didn’t match the breadth of the federal law. Assemblyperson Amy Paulin and Senator Andrew Lanza, who co-authored the Safe Harbor law, recognized loopholes and weaknesses they’d need to address in future laws.

For starters, the Safe Harbor law didn’t protect 16-and-17-year-old minors, who had to prove coercion to earn trafficking victim status.

Additionally, the Safe Harbor law did not criminalize the act of buying sex from minors. Johns could only get charged with commercial sexual exploitation of children, which carried lower penalties than statutory rape. In many cases, having sex with a child was a worse crime than buying sex from a child. This loophole didn’t make sense, and legislators sought to align penalties for trafficking and statutory rape in subsequent legislation.

In 2010, an amendment to the New York Vacating Convictions Law let trafficking victims retroactively vacate prostitution-related arrests, offenses and convictions from their records.

Vacatur “thus provides increased protection and a second chance for survivors of human trafficking to begin living normal lives,” according to The Polaris Project, an anti-trafficking organization.

A work in progress: The Trafficking Victims Protection and Justice Act (TVPJA)

Paulin and Lanza co-authored the Trafficking Victims Protection and Justice Act (TVPJA), a bill intended to fix and strengthen the existing anti-trafficking law and address new issues. Unfortunately, the bill failed to pass through the assembly in June 2013. But, one part of the bill became a separate law last month.

On January 10, Governor Cuomo signed into law a bill classifying all minors who commit prostitution as PINS (Persons in Need of Supervision).

The Safe Harbor law only recognized 16-and-17-year-old children in prostitution as victims if they proved coercion. The process of proving coercion could re-traumatize sexually exploited kids. Federal trafficking law considers all minors in prostitution victims, so the PINS law aligns state and federal requirements for victim status.

Paulin plans to reintroduce the TVPJA’s other provisions soon.

“To that end, I will continue to work this session to pass the Trafficking Victims Protection and Justice Act to increase the accountability of the real criminals,” she said in a press release. “The buyers and traffickers, who continue to fuel the growth of this massive industry that preys on our most vulnerable members of society. Remember, people are not for sale.”

TVPJA pending provisions:

Greater penalties for traffickers and johns: Trafficking would become a violent felony (up from a regular felony), on the basis that sex traffickers subject victims to repeated rape by johns, and rape is a violent crime.

To hold johns more accountable for buying children, the TVPJA creates the offense of “aggravated patronizing a minor,” which would carry equal penalties to statutory rape.

Protecting victims from prosecution: Going further than the 2010 vacatur bill, the TVPJA establishes sex trafficking as an affirmative defense to prostitution. This would eliminate the need for post conviction challenges to clear victims’ records.

Prosecuting traffickers’ helpers: Traffickers have increasingly relied on livery and town car drivers to transport victims. The TVPJA proposes amending the penal law so the state can prosecute anyone “engaging in the business or enterprise of transporting people to sell them for sex.”

Broadening the definition of trafficking: Because traffickers commonly use ecstasy to impair and control victims, the TVPJA proposes that “providing ecstasy with the intent to impair judgment” constitute trafficking.

Retiring the word prostitute: The use of “prostitute” is the only instance where state law refers to someone by the crime he or she allegedly committed. The TVPJA proposes replacing the word “prostitute” with the phrase “person for prostitution.” Using “prostitute,” according to the TVPJA website, amounts to blatant gender bias and unnecessary stigmatization of trafficking victims.

Trafficking reform in the Court Room:

Chief judge of the State of New York Jonathan Lippman announced in September 2013 a statewide system of Human Trafficking Intervention Courts. The 11 courts take all prostitution related cases that go past arraignment. Judges, defense attorneys and prosecutors jointly evaluate cases with a focus on providing social services and training programs to reboot victims’ lives. This court system is new, but New York’s two other specialized court systems, for domestic violence victims and minor drug offenses, have been successful.

Sex Trafficking at the Super Bowl:

All 50 states have some kind of anti-trafficking law. According to the Polaris Project, an anti-human trafficking organization, New York and New Jersey have among the most comprehensive trafficking laws in the country. But the tri-state area criminal justice community is bracing for February 2, when the Super Bowl takes place at Met Life Stadium in East Rutherford, New Jersey.

On average, 77,987 flood the Super Bowl arena on game day – it’s easy to blend in, and sex traffickers do. For about five years, various law enforcement entities and anti-trafficking organizations have declared the Super Bowl “the Super Bowl” of American sex trafficking. Though statistics are hard to come by, The Florida Commission Against Human Trafficking estimated that tens of thousands of women and children were trafficked at the 2009 Super Bowl In Tampa.

Elected officials and advocates started planning in October to cut down on game-time trafficking. Acting Attorney General John Hoffman created a task force of law enforcement, advocacy organizations, social workers, and community members. Employees of nearby hospitals and hotels have undergone training to spot victims.

“As with all victims of human trafficking, adolescent girls may display symptoms of Stockholm syndrome,” according to a 2007 Department of Health and Human Services report. “[They] express extreme gratitude over the smallest acts of kindness or mercy (e.g., he does not beat her today), denial over the extent of violence and injury, rooting for her pimp, hyper vigilance regarding his needs, and the perception that anyone trying to persecute him or help her escape is the enemy.”

Story produced by the New York Bureau

Pingback: Human Trafficking in America’s Backyard | Girls' Globe