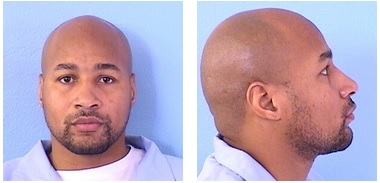

Adolfo Davis, currently in custody at Stateville, is seeking retroactive application of Miller v. Alabama in his case." credit="

CHICAGO — In 1990, Adolfo Davis and two other members of Chicago’s Gangster Disciples were involved in a shooting with a rival gang that left two people dead. Although Davis never fired his gun, he was charged as an accomplice and sentenced to life without parole, the mandatory minimum sentence in Illinois.

At the time, Davis was 14. He has since spent more than two decades in prison. However, after a June 2012 Supreme Court decision, Miller v. Alabama, which ruled mandatory sentences of life without parole unconstitutional for juveniles, Davis is appealing his sentence. The SCOTUS decision was made under the Eighth Amendment’s “cruel and unusual” punishment prohibition, which “guarantees individuals the right not to be subjected to excessive sanctions.”

The Miller v. Alabama ruling

The Miller v. Alabama case involved the petitioner, 14-year-old Evan Miller, who along with a friend, had beaten Miller’s neighbor and set fire to his trailer. Miller was tried as an adult and sentenced to a mandatory punishment of life without parole.

The Supreme Court ruled that the sentence was unconstitutional after examining other cases that set precedent, including Roper v. Simmons and Graham v. Florida. Roper v. Simmons barred capital punishment for children, and Graham v. Florida said, “…The Amendment prohibits a sentence of life without the possibility of parole for a juvenile convicted of a non-homicide offense.” Justice Elena Kagan, who wrote the opinion, stated “Graham further likened life without parole for juveniles to the death penalty itself.”

The Supreme Court ruled that the sentence was unconstitutional after examining other cases that set precedent, including Roper v. Simmons and Graham v. Florida. Roper v. Simmons barred capital punishment for children, and Graham v. Florida said, “…The Amendment prohibits a sentence of life without the possibility of parole for a juvenile convicted of a non-homicide offense.” Justice Elena Kagan, who wrote the opinion, stated “Graham further likened life without parole for juveniles to the death penalty itself.”

These cases tie into the psychological state of juveniles – the underdeveloped brains and lack of maturity that juveniles tend to exhibit subjects them to take more risks and be more impulsive. The Roper and Graham cases show that juveniles have differing characteristics than adults, which then make it harder to justify harsh penalties on juveniles, regardless of the severity of the crime. In the end, Kagan wrote that all juveniles convicted of murder should be given a sentence directly related to their age and their involvement in the crime.

Varying states’ responses

According to the National Center for Youth Law (NCYL), the Miller ruling created four issues for the states. The states had to address “bringing their sentencing statutes into compliance with the ban on mandatory sentencing, determining whether the ruling is retroactive, providing youth with a meaningful and realistic opportunity for release, and reforming their juvenile-to-adult court transfer processes in general.”

Two of the main points are the changing of sentence statutes and the determination of whether applying the ruling would be retroactive. According to the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, at least 27 states were affected by the ruling.

California, Wyoming, and Delaware immediately recognized the differences between adults and children and eliminated juvenile life without parole completely.

In Pennsylvania and North Carolina, juveniles convicted of second-degree murder can no longer be sentenced to life without parole.

Connecticut is also working on House Bill 6581, which would ban life without parole sentencing for youth, and increase the opportunities for parole for those who had served “prison sentences of more than 12 years for crimes committed before their 18th birthdays.” Although the bill was not voted on in the Senate before the legislative session adjourned, supporters anticipate action on the bill in the 2014 session.

Another state that responded swiftly to the federal mandate was Iowa; a week after the Supreme Court made their decision in Miller v. Alabama, former Iowa Gov. Terry Branstad reduced all juvenile life without parole sentences to life without parole after 60 years. However, some argue that this reduced sentence may be almost equivalent to a life sentence.

In August 2013, a Michigan judge also upheld the life-without-parole sentencing ban for juveniles, which meant that over 350 prisoners became eligible for parole hearings after being sentenced to life without parole as juveniles. This is also significant because Michigan has the second-highest number of juveniles sentenced to life in prison, following Pennsylvania.

Looking at Illinois, in terms of the Adolfo Davis case, the biggest question remains: is Miller v. Alabama retroactive? Because the court did not specify in the ruling whether the decision should be applied retroactively, Davis’ case will be the first to be examined by the Illinois Supreme Court and could set precedent for the close-to-100 other inmates in Illinois serving a mandatory juvenile life without parole sentence.

The retroactivity of Miller

During the January opening oral arguments in Davis, prosecutor Alan Spellberg argued that the Supreme Court’s decision should not be applied retroactively on existing sentences. Spellberg said that those who are currently serving juvenile life without parole sentences should appeal Gov. Pat Quinn for clemency; Davis requested clemency two years ago and still has not received a decision.

On the other hand, Davis’ attorney Patricia Soung told the Chicago Tribune that she believed the large “watershed” effect of the law meant that the state needed to review current juvenile life without parole sentences.

Jobi Cates, the director of Human Rights Watch in Chicago, agreed with Soung, saying that juvenile life without parole cases do need to be reviewed.

“It is difficult to look at these cases and reevaluate things that happened…you have to weigh the horrific harm that was done to an individual against individuals whose rights are being violated [by juvenile life without parole],” Cates said. “What’s worse?”

Cates also stated that the Adolfo Davis case and other juvenile life without parole cases meet the Teague exceptions. The Teague v. Lane case did bar retroactivity, but the Supreme Court also gave two exceptions in which retroactivity may be applied. The court said that a new law may be applied if (1) “it places ‘certain kinds of primary, private individual conduct beyond the power of the criminal law-making authority to proscribe’” or (2) “requires the observance of ‘those procedures that . . . are ‘implicit in the concept of ordered liberty.’”

According to these exceptions, juvenile life without parole sentencing goes against the “observance of ‘those procedures that…. are ‘implicit in the concept of ordered liberty,’” since the mandatory sentencing procedure does not take into account the age of the offender or circumstances of the crime.

Therefore, retroactivity in these cases can be applied because the petitioner was once denied a form of due process since the sentencing was ruled unconstitutional.

The United States is the only country to ever have a life without parole sentence for a juvenile. Elizabeth Clarke, president of the Juvenile Justice Initiative, believes that the juvenile life without parole sentence is also “…violative of international human rights as it is expressly prohibited in the Convention on the Rights of the Child,” and that the Miller case should be applied retroactively to fight against the injustice.

With the Adolfo Davis sentence appeal set to be decided at any time, the fate of the others serving juvenile life without parole sentences in Illinois will fall into the hands of the precedent set by the case.

This story produced by the Chicago Bureau