Earlier this month, JJIE columnist John Lash devoted a long commentary to a controversial new study that is currently making waves throughout the Oregon juvenile justice system.

Written by Clackamas County District Attorney John Foote and retired Multnomah County Deputy District Attorney Charles French, the study concluded that, because the state adopted a “reformist” agenda promoted by the Annie E. Casey Foundation, Oregon has suffered with “significantly worse juvenile crime results” than the rest of the nation. In the realm of adolescent drug abuse, the new study asserted, “Oregon’s performance in the Casey Foundation era borders on catastrophic.”

In his column, Lash concedes he “is not enough of a statistician or researcher” to assess the assertions made in the report, but he warned that its findings should not be dismissed out of hand.

“It is our nature to ignore contrary evidence,” Lash cautioned, “especially when it goes against not only our philosophical position but is contrary to our livelihood as well.”

I agree. I do not dismiss the report out of hand. But unlike Lash, I do know my way around the data. So last week I took time to review the report, assess its claims and scrutinize the analysis beneath them.

I quickly found that the report is riddled with logical fallacies, ungrounded assumptions, deceptive analyses and blatant cherry picking of data points to justify its anti-reformist conclusions.

Now, I do not claim to be a neutral observer. While I am not a Casey Foundation employee, I have done extensive paid work for the Foundation and written many of its publications on juvenile justice. So my objectivity might be questioned.

But when it comes to the Foote/French report, my objectivity is beside the point. The flaws in the publication are glaring, the biases brazen. Simply put, this is not a piece of serious scholarship.

(To be clear, the Casey Foundation did not pay me to write this column, and no one at the Foundation encouraged me to write it or influenced its conclusions.)

A false and misleading dichotomy

The problems with the Foote/French report begin at the beginning.

The preface quickly establishes the central dichotomy of the report. The very first paragraph extols the state’s juvenile justice statute, a 1995 package known as Senate Bill 1, and lauds the law’s emphasis on “early and certain intervention and sanctions” as the most effective way to hold juveniles accountable for their criminal behavior. The second paragraph laments that “many of Oregon’s juvenile departments have abandoned the principles of Senate Bill 1 through the influence of a large out of state private non-profit organization called the Annie E. Casey Foundation.”

Foote and French then go about building their case that juvenile justice outcomes in Oregon have been seriously damaged by the state’s embrace of reform strategies advocated by the Casey Foundation.

Throughout the report, they assign credit (or rather blame) to the Casey reform agenda for all juvenile justice outcomes throughout the state of Oregon.

Yet, the Casey Foundation has never been active in most of the state. Rather, beginning in the early 1990s, Multnomah, Oregon’s largest county at 19 percent of the state population, became a pilot site in Casey’s Juvenile Detention Alternatives Initiative (JDAI). In 2005, a coalition of 10 rural counties with a combined population of just 181,000 — less than 5 percent of the state population — also signed on as JDAI sites.

Oregon’s other 25 counties, home to 76 percent of the state population, never adopted the JDAI model, and unlike many other states, Oregon’s state government never signed on as a partner or committed itself to supporting JDAI replication statewide. Yet the entire Foote/ French analysis is based upon the dubious notion that Casey has co-opted the Oregon juvenile justice system in its entirety.

A rotten core

The core of the Foote/French argument rests upon the contention that — due to JDAI and other Casey-inspired practices — Oregon has suffered troubling juvenile crime outcomes. But this premise is plainly false. Particularly in Multnomah County, juvenile arrests rates have fallen dramatically since JDAI was introduced in the mid-1990s.

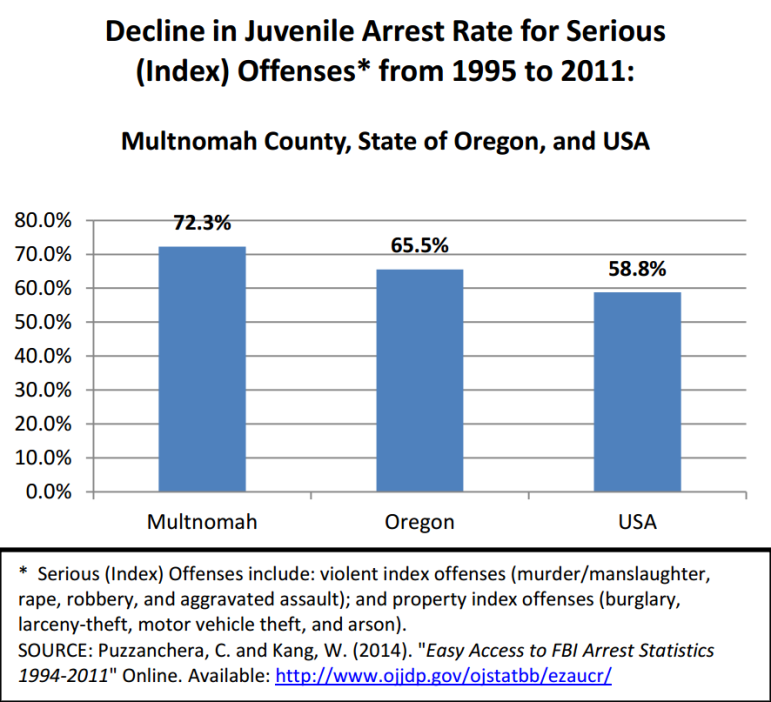

Since 1995, the total juvenile arrest rate in Multnomah is down 72 percent, and the juvenile arrest rates for violent index crimes, property index crimes and non-index offenses are down by 80 percent, 72 percent and 71 percent respectively. All these declines far surpass the statewide average in Oregon, which in turn surpass the national averages (See chart 1.)

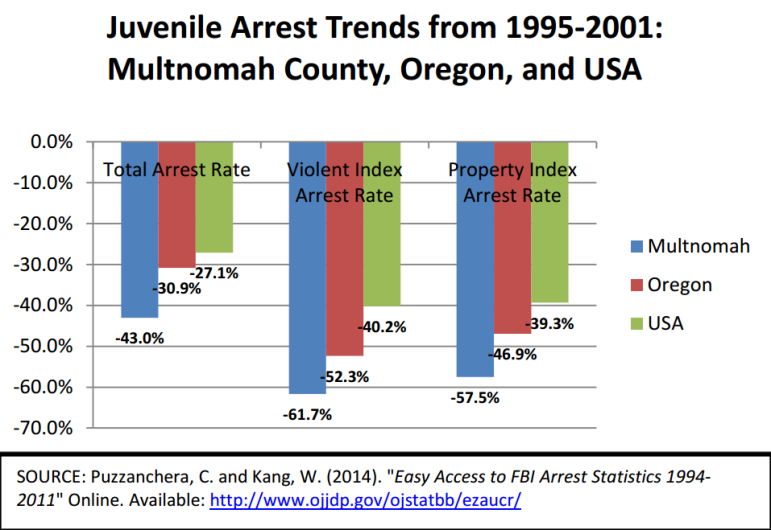

Without explanation, the Foote/ French report examines data only from the period of 2001 to 2011, excluding arrest trends during JDAI’s first six years in Multnomah (1995 to 2001). (See chart 2.) Yet during this six-year period the juvenile arrest rate for violent index crimes in Multnomah fell a whopping 62 percent, and the rate for property index crimes fell 58 percent. Again, these results far surpassed the progress statewide in Oregon, which in turn surpassed the progress nationwide.

Employing a nifty rhetorical trick, Foote and French refuse to grant JDAI any credit for the impressive declines in juvenile arrest rates for violent offenses. Instead, they attribute all progress against juvenile violence to a punitive state law (Measure 11) that mandates that youth accused of serious violent offenses be tried and punished as adults. This claim runs contrary to all research evidence and to the actual experience in Oregon.

As JJIE readers are likely aware, the available research consistently finds that transferring youth to adult courts and corrections systems leads to more crime, not less. Both the National Academy of Sciences and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control have reviewed the research and concluded that youth transferred to adult courts recidivate at higher rates than youth who are adjudicated, sanctioned and treated in the juvenile system.

Moreover, carefully controlled research studies have showed that aggressive transfer laws are not associated with lower juvenile crime rates. In other words, these laws don't work as a vehicle for general deterrence (where kids offend less often based on fear of punishment). Rather, studies find that jurisdictions enacting aggressive transfer laws (like Measure 11) have not seen any improvement in juvenile offending when compared with similar nearby jurisdictions where juvenile courts retain jurisdiction over comparable cases.

For instance, after Idaho passed a law in 1981 requiring transfers for all youth accused of violent crimes, its youth violence rate increased while the rates fell in neighboring Montana and Wyoming, where transfers were not mandated. Likewise, a 1997 New York law lowering the age at which youth could be transferred to adult court had no deterrent effect.

Within Oregon, a 2011 study ("Misguided Measures" by the Campaign for Youth Justice and Partnership for Safety and Justice), found that the counties that relied heavily on Measure 11 to charge and prosecute youth as adults had no more success than other counties in lowering their rates of juvenile crime and violence. And again, the data from Multnomah County show that violent index arrests fell precipitously when JDAI was introduced, far more than in other Oregon jurisdictions, even though Measure 11 was enacted statewide.

Foote and French then move on to other offending categories. Ominously, they warn that “as its juvenile justice system has increasingly adopted Casey practices over the past decade, the state has continued to produce significantly worse juvenile crime results than mainstream systems in all areas of non-violent crime.”

Yet, as the Foote/ French report itself shows, Oregon’s juvenile arrest rate for serious property crimes fell 34.7 percent over the 10 years they studied (2001 to 2011), whereas the national rate declined 32.2 percent. Foote and French lament that Oregon’s juvenile property crime arrest rate is “among the worst in the nation.” Yet they omit to mention that Oregon’s juvenile property crime arrest rate has long exceeded the national rate, and that the gap has been shrinking steadily throughout the years that Casey and JDAI have been active in parts of Oregon.

In further criticizing the Oregon juvenile justice system's public safety performance, Foote and French place great emphasis on rising juvenile drug arrest rates and negative juvenile drug abuse trends in the state. Yet, they significantly overstate the problem, and their claim that JDAI and the Casey Foundation are the primary cause of rising adolescent substance abuse in Oregon has no basis.

Adolescent substance abuse is a complex phenomenon affected by a wide range of social, cultural, personal and economic forces. I am aware of no evidence — and Foote and French provide none — indicating that juvenile justice policies are a pivotal factor in the equation. Attributing statewide adolescent drug abuse trends entirely to JDAI, which operates only in Multnomah and 10 small central Oregon counties, is even more of a stretch.

Meanwhile, the very data set Foote and French rely upon to show that adolescent drug abuse has worsened in Oregon over the last decade — the National Survey on Drug Use and Health— reveals that drug abuse has been increasing far more rapidly among Oregon’s adult population, including both young adults (18 to 25) and older adults (26-plus).

On a wide variety of measures, Oregon adults have seen major increases in drug abuse over the past decade — far greater than the increases among Oregon adolescents, and far greater than the trend for adults in other states. Indeed, Oregonians aged 26 or older now have the highest rates of drug dependence in the nation. Clearly, this is not a function of JDAI. Rather, Oregon is suffering a public health crisis with respect to drug abuse.

Foote and French are correct that the juvenile arrest rate for drug offenses has risen lately, but they then make the groundless claim that “Higher juvenile drug arrest rates in Oregon are not the result of enforcement policy … High juvenile drug arrest rates are the product of high juvenile drug use.”

To support this contention, they cite data showing that Oregon youth had high rates of overall drug abuse, cocaine use and marijuana use in 2011 — ranking among the top 12 states in each category. What they don’t mention is that Oregon youth also had higher than average rates in earlier years, meaning that juvenile drug abuse in Oregon has increased only modestly in recent times. The share of Oregon adolescents using drugs in the past month increased just 3 percent between 2002-03 and 2010-11 (versus a 28 percent rise for Oregon adults), whereas juvenile drug arrests rose by 46 percent over a similar period. In short, the trend toward rising drug arrests is due almost entirely to more aggressive policing.

Redefining the meaning of ‘mainstream’

Using a similar mix of sophistry and deception, Foote and French also attempt to show that the Oregon juvenile justice system has grown financially wasteful under the Casey Foundation’s influence, that juvenile recidivism rates are unusually high in Oregon (especially in JDAI counties), and that JDAI sites nationwide have suffered poor public safety outcomes. Their arguments are again unpersuasive.

Far more insidious are sections of the report that strive to frame the larger discussion. Foote and French repeatedly bemoan what they term a “reformist” trend in juvenile justice “that seeks to drastically alter the practices of juvenile justice policy.”

They present a series of charts showing that compared with most other states, Oregon closes a much larger share of juvenile cases at intake (imposing no sanction), formally petitions a far lower share of juvenile cases, confines youth far less frequently in pretrial detention and places fewer youth into detention based on probation violations.

Time and again, Foote and French attribute these practices to the influence of the Casey Foundation and characterize them as a drastic turn away from “mainstream” approaches to juvenile justice. (The word “mainstream” appears 12 times in the report, always in contrast to the reform agenda being denigrated.)

Indeed, the policies favored by Foote and French — widespread transfers to adult court, heavy use of confinement, aggressive prosecution, minimal use of diversion — were in the mainstream of juvenile justice practices 20 years ago when Oregon, like so many other states, enacted get-tough legislation in the midst of a nationwide juvenile crime panic.

Since then, and with increasing speed, juvenile justice systems coast to coast have been reversing course. Twenty years ago Multnomah County was one of five jurisdictions in the nation active in JDAI. Now more than 300 jurisdictions in 40 states are replicating the model. In the 1990s, 44 states enacted laws to increase the number of youth transferred to the adult justice system. More recently, a wave of states have been raising the age of juvenile jurisdiction and making other changes to reduce transfers.

Meanwhile, a growing number of states, several with support from the Pew Trusts, are enacting far-reaching juvenile reform laws designed to divert more youth away from the juvenile courts and to expand community treatment and reduce the use of confinement for youth whose cases are adjudicated. These include both some of the nation’s most conservative law-and-order states — Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Nebraska and Texas — as well as blue and purple states like California, Hawaii, New York and Ohio.

These changes are coming thanks to the growing evidence that data-driven and treatment-oriented juvenile justice strategies typically produce lower recidivism and better long-term outcomes at lower cost. The evidence was neatly summarized last year by the National Academies of Science last year in its report, Reforming Juvenile Justice: A Developmental Approach, which declared that “there is no evidence that more severe punishments reduce the likelihood of future offending.”

My point is not that Foote and French are wrong to examine the impact and effectiveness of JDAI, or to question the wisdom of reform strategies being pursued in Oregon (or anywhere else). There remain many unanswered questions regarding what works and doesn’t in combatting delinquency and many legitimate questions to be raised about how well many popular juvenile justice reform ideas work in actual practice. (For examples, see my recent JJIE column questioning the evidence behind leading evidence-based prevention and treatment models.)

Skeptical inquiry is exactly what the juvenile justice field needs. But questioning and criticism is useful only to the extent that it is conducted objectively and presented with intellectual integrity.

Unfortunately, Foote and French fail that test. Employing unsound logic and disingenuous analyses, their report represents a last-gasp effort to tune out the evidence and turn back the clock. It espouses the return to a wrong-headed, counterproductive and often cruel vision of juvenile justice that’s thankfully dying out not only in Oregon, but nationwide — and for good reason.

Dick Mendel is an independent writer and editor on juvenile justice and other youth, poverty and community development issues. He has written nationally disseminated reports for the Annie E. Casey Foundation, American Youth Policy Forum and Justice Policy Institute, among others.

This was a needed and well-done analysis that shows JDAI – and similar efforts – is more than just “drinking the kool-aid” of reform and actually demonstrating reform that both reduces youth incarceration (and the pitfalls that come with it) and contributes to long-term community safety. It is important that proponents of JDAI and other informed reforms attend to both outcomes as a goal in promoting cost-effective, community-based prevention and intervention efforts. In this case the analysis appropriately takes to task the Foote and French methodology and conclusions while at the same time demonstrating the need for continued, if not increased, vigilance to ensuring the reforms that are promoted are accountable.

Thanks for doing this. Watching policymakers in Oregon (where I once lived) be excited and engaged by that idiotic Foote “study” has been frustrating to those of us who try to analyze youth justice with attention to accuracy and fairness.

Excellent response to the Foote and French letter. I led my county to in 2003 to become a JDAI site as our county was going through a transition and delinquency filings were soaring. I read the “What Works” literature (and having experienced as a deputy director in adult parole responsible for offender program statewide) and elected to pursue what some would accuse me as soft though today we are convinced its smart. Our average daily detention population in 2002 (the year before we joined JDAI) was 72–today its approximately 10. Our commitment rates to state custody fell 43 percent. Despite this “let em go” approach that a Foote and French would inflammatorily label, our delinquency filings are down 62 percent–and this cuts dramatically across all categories (persons, property, drugs, weapons, and public order). And may I add, this is in the poorest county of all of Atlanta where all students get a free lunch. Even law enforcement executives who have been around for a while will say we cannot arrest our way of this problem. It appears Foote and French have an underlying motive they are not sharing; or why else deliver such a slanted, biased, and illogical report.