Brooke L. Williams

At the age of 17, Jeffrey Deskovic was convicted of raping and murdering his high school classmate. After spending 16 years in prison for the crime, Deskovic was exonerated in 2006. He stands inside his office at the Jeffrey Deskovic Foundation where he works to free others who have been wrongfully convicted. “It was intended to be a legacy,” says Deskovic. “Something to make my mark on the world and to survive me.”

NEW YORK — When Jeffrey Deskovic was a kid he wanted to be a cop. When he got a little older, he decided instead that he wanted to be an attorney. They wore nice suits. They made good money.

Today, Deskovic owns plenty of suits and has earned a sizeable income, but he never fulfilled his childhood dream of becoming a lawyer. Instead, he works as a criminal justice reform advocate.

Today, Deskovic owns plenty of suits and has earned a sizeable income, but he never fulfilled his childhood dream of becoming a lawyer. Instead, he works as a criminal justice reform advocate.

In late 1989, at the age of 16, Deskovic came under suspicion for the brutal rape and murder of his high school classmate Angela Correa. After being held in an interrogation room for about eight hours with no parent or attorney present, he confessed to the crime.

He was innocent.

A vulnerable population

“I was just totally overwhelmed, psychologically and emotionally,” Deskovic said. “By the cop’s own testimony, at the end of the interrogation I was on the floor in a fetal position.”

A scared teenage boy, he thought if he gave the officers what they wanted, a confession, he would be released from custody and allowed to return home. He believed the police when they told him he would only have to go to a mental hospital for a short period, that he would not serve any jail time.

Mostly, he just wanted to get out of there. Instead, his life was forever altered.

After his arrest, Deskovic was released on bail. While awaiting trial, he tried to kill himself.

“I took an entire bottle of extra-strength Tylenol and then I went to sleep intending not to wake up again,” he said.

He was committed to Rockland Children’s Psychiatric Center, where he remained from March to August 1990.

In January 1991, Deskovic was convicted of raping and murdering Correa despite a semen sample from her that was traced to a then-unidentified person. Prosecutors maintained that Correa could have had consensual sex with another person before her murder. A Westchester County District Attorney’s report notes that Deskovic promised at his sentencing: “I will be back on appeal. Justice will yet be served. I will be set free.”

According to the Innocence Project, a group that examines wrongful convictions and was involved in Deskovic’s exoneration, more than 25 percent of people wrongfully convicted and eventually exonerated made “false confessions or incriminating statements.” Studies show that those under 18 are particularly susceptible.

So on January 1991 a 17-year-old with no prior criminal record found himself thrust into a prison culture that does not treat sex offenders, real or perceived, kindly.

‘I have a body’

At the entrance to Elmira Correctional Facility stands a bronze statue of two prisoners side by side, one with an arm draped around the other. The statue was intended to be a symbol of the days when Elmira’s “wayward boys were transformed into law-abiding men.”

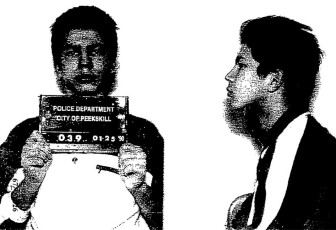

Photo courtesy Jeffrey Deskovic

By the time Deskovic got there, it was known as a junior gladiator school where young boys were inducted into the culture of prison violence, he said. Sex offenders were particularly singled out. If other inmates asked, Deskovic learned to respond only with ‘I have a body’ — prison slang for doing time for murder.

He had few friendships during his nearly 16 years in prison. Instead, he had what he calls “associations.” Friendships were likely to lead to violence. It was better to keep your distance. His mother was his only regular visitor. His half-brother seldom came. His grandmother, with whom he was particularly close, died while he was incarcerated. He met his father for the first time only after his release.

Deskovic passed the time by watching television. He liked “The Practice,” a drama about lawyers, and “WWE SmackDown.” He enjoyed listening to sports talk radio, noting that “it was like a lifeline to the outside.” He played sports.

“I would engage in this elaborate delusion,” he said. “When I played basketball or ping-pong or chess, I would pretend I was like a professional player and so was everyone else.”

Held captive by the past

Throughout it all, Deskovic insisted he was innocent. After twice contacting the Innocence Project, the organization agreed to take his case in January 2006. To date, the organization has successfully exonerated 176 people by using DNA evidence to overturn convictions.

Deskovic joined those ranks in September 2006 after DNA from the crime scene was matched to the actual perpetrator, a convicted felon already serving time for another murder.

On Nov. 2, 2006, he was officially exonerated of Correa’s murder. He eagerly looked forward to his long-awaited freedom.

“I guess I could call it an idealized life,” Deskovic said. “I mean, the life I thought I was walking into.”

“I guess I could call it an idealized life,” Deskovic said. “I mean, the life I thought I was walking into.”

He thought he would find a job, get promoted, return to a normal life. His declaration in a Westchester County courtroom years earlier had finally come true.

But reality did not meet expectations. Deskovic was a free man, but one still held captive by his past.

“I thought I would go to all these different places and do all these different activities that I saw on television that I wanted to do,” he said. “The monetary component of that never dawned on me. Like it never dawned on me having people to do things with was something that couldn’t be taken for granted.”

Discharged from a time capsule after 16 years

Betrayed once by trust in a criminal justice system that had failed him, Deskovic now seemed betrayed by a world he no longer recognized. He had been stuck in a time capsule for 16 years. Meanwhile, the outside world continued to evolve without him.

“There’s a lot more external stimuli out here that’s not replicable in a prison setting,” he said.

Plus, he had never lived on his own before, never balanced a budget, never learned to pay bills. Everyday things like sorting through junk mail were difficult.

In prison, “mail was just given to you and it wasn’t that often that it came,” he said.

Deskovic suffered from anxiety, panic attacks and depression. He was one age but felt another, a sentiment observed by Shelley Alkin, a former dean at Mercy College. After reading about Deskovic’s case in late 2006, she called to offer him what he considers one of his few lucky breaks — a full scholarship to attend Mercy.

Alkin was no stranger to working with the formerly incarcerated at Mercy College, which partners with a private organization to help inmates earn advanced degrees while in prison.

Nevertheless, she described her first encounter with Deskovic as shocking. He looked like he was wearing hand-me-down clothes. He brought ramen noodle soup and a bowl with him and asked to heat it in her microwave.

The students at Mercy were polite, but far from welcoming. There is a stigma to spending 16 years in prison, whether you are innocent or not, Alkin noted. After spending years locked up on the inside, Deskovic said he now found himself “on the outside looking in.”

Alkin recalled when they embraced for a hug, “I felt like sometimes he was just holding onto me for dear life.”

While in lockup, Deskovic converted to Islam but stopped practicing a year after his release because of its restrictions on drinking, nightlife and sexual relations.

At 33, he has never had a serious romantic relationship. Learning how to read women’s body language and pick up on social cues was difficult. It is something he still struggles with today.

His friend Nancy Lopez, who Deskovic considers himself closest to, tries to help him with that.

He met her two years after his release while he was living in Tarrytown, N.Y., and she was working as a waitress at a local diner. Two weeks after their first meeting, he injured his leg while playing basketball and phoned Lopez for help. She drove him to the hospital and offered to let him stay with her until his leg healed.

“I took her up on her offer and never quite left,” Deskovic said.

When he was awarded several million dollars in separate settlements with New York state and Westchester, Peekskill and Putnam counties for his wrongful imprisonment, he upgraded to a two-family home and invited Lopez to stay with him.

Deskovic occupies the first floor, Lopez the second. Her adult son stays on the basement level. Lopez says she makes most of the meals since Deskovic is not the best cook.

“The only thing he can make for me is a cup of coffee in the morning,” Lopez said.

Still searching

Today, Deskovic bears little outward resemblance to the man who was released from prison more than eight years ago. The overgrown beard he once sported is gone, replaced with a goatee. Lopez says it was her son’s idea.

The timbre of his voice is deeper. He’s packed on a few pounds and likes to eat out. Italian food is his favorite and “anything with sauce on it.” Lopez said he also likes vegetables and she tries to cook healthy meals for him. “That way he can lose a little weight too,” she said.

Most of Deskovic’s time is now spent at The Jeffrey Deskovic Foundation for Justice, an organization he founded with a portion of his settlement money. His office is in the back of a building on the upper west side of Manhattan. The walls are painted blue, his favorite color.

That’s not the reason he chose this particular shade of paint, though. He chose it for sentimental reasons. He liked the name: It’s called “Grandma’s Sweater.”

On the wall, amid other framed accolades, hangs the degree he earned from Mercy. The master’s degree he earned from the John Jay College of Criminal Justice in 2013 isn’t there.

He has been too busy to pick it up. Busy at the foundation, he says, working to free others wrongfully convicted. Others like William Lopez, the foundation’s first and only successful exoneration case to date.

Through the foundation’s assistance, William Lopez (no relation to Nancy Lopez) was exonerated in January 2013 after serving 23 years in prison. Deskovic says William’s release from prison is the happiest moment he has experienced post-incarceration. The celebration, however, was short-lived. William Lopez passed away in September 2014 from an asthma attack.

At the foundation, Deskovic’s staff of four is currently working on eight cases. He is hopeful a second exoneration will result soon. He provides temporary housing in a two-bedroom Manhattan apartment for those recently released.

"I’m personally so proud of him and how far he’s come," Alkin said.

Nancy Lopez says Deskovic still suffers from the psychological scars of his past, though. He has nightmares and bouts of depression.

“What they did to him is still there. He still has the scars fresh in his mind,” she said.

Deskovic acknowledges he does not sleep well but says he is doing better. While his professional life and advocacy work keep him occupied, his social calendar is not always as full.

“Where are my peers at? Where are they at?” implored Deskovic.

He can’t seem to find them. He wants friends with common interests.

“Not all of them, not every interest,” he said. “But maybe half of them so we can change genres of activities, kind of like I did when I was a kid.”

He is still searching for them. He is still searching for a life partner. And while that search continues, he wants the world to know that he is single and available.

He finally got around to picking up that master’s degree from John Jay College. He has plans to have it framed and hanging on his wall soon.