A dozen years ago, former Wall Street Journal columnist Thomas Frank wrote an unlikely best-seller, “What’s the Matter With Kansas?” It examined why that state’s once moderate voters had swung hard right in their political leanings, and why less affluent Kansans were consistently voting for ultraconservatives advocating sweeping policy changes that conflicted with these voters’ economic interests.

Frank’s book did not focus on juvenile justice. But while Kansas politics have continued to lurch ever rightward, the state has made encouraging strides in reforming its juvenile justice system. In April, Kansas enacted an ambitious new law sharply restricting the use of incarceration for youth, shortening lengths of stay, limiting confinement for violations of probation and expanding evidence-based community treatment programs.

And it’s not just Kansas. Many other states, including several in the South (Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, South Carolina, Texas and West Virginia), have also embraced the evidence showing that family-focused and community-based interventions work better than confinement to combat delinquency — and have implemented sweeping reforms to put these ideas into practice.

But then there’s Arkansas.

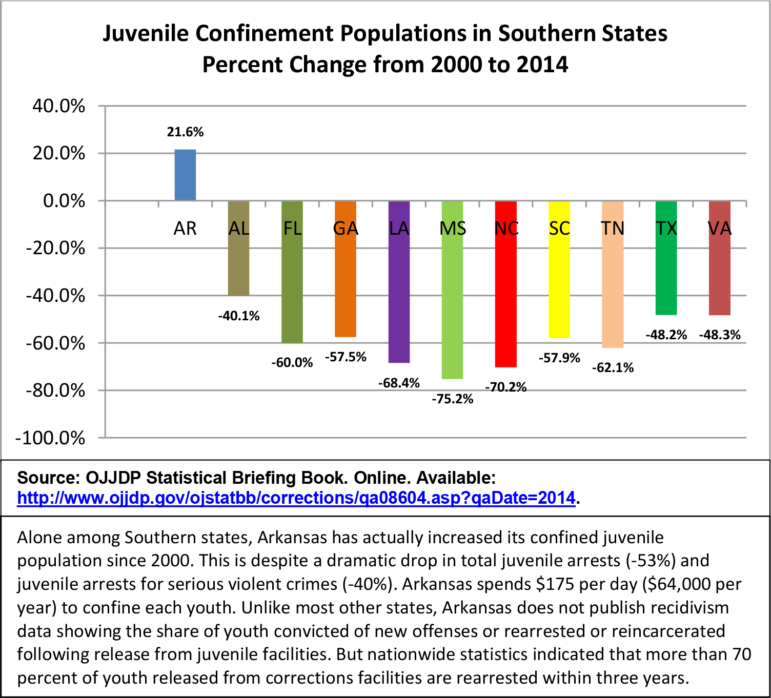

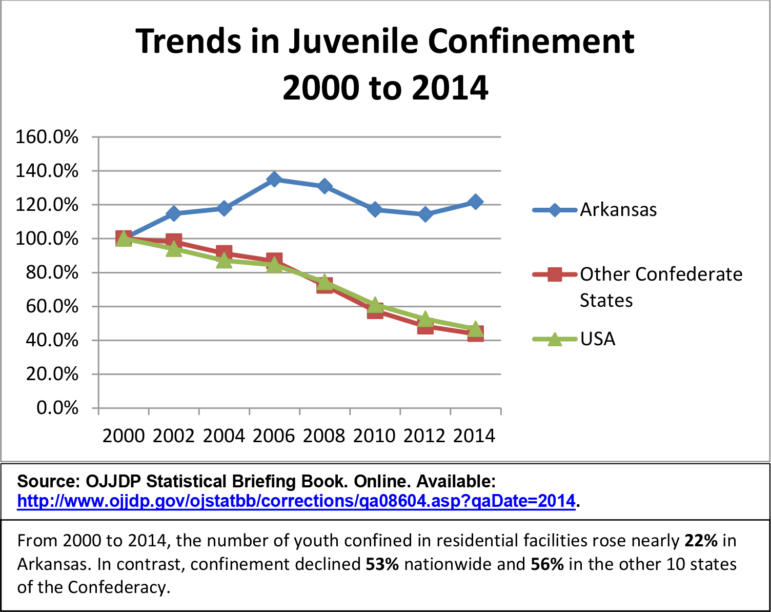

Over the last two years, Arkansas’ juvenile justice system has burst onto the scene repeatedly … and for all the wrong reasons. In August 2014, the Disability Rights Center released a report documenting alarming conditions in the state’s largest juvenile correctional facility. While juvenile incarceration rates nationwide have been plummeting, Arkansas has actually increased the number of commitments in each of the past two years despite a continuing drop in juvenile arrests statewide.

Arkansas has also been in the national news spotlight because one of its U.S. senators, Tom Cotton, has single-handedly derailed reauthorization of the federal Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act. His stance reflects the position of numerous juvenile judges in Arkansas who, despite an overwhelming consensus in the field, oppose plans to close a longstanding loophole in the federal government’s prohibition on confining status offenders.

In 2015, a reporter for the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette published a series of investigative stories documenting the state’s continuing penchant for jailing children brought to court for skipping school, running away from home, disobeying their parents, drinking alcohol or breaking other rules aimed only at children. The reporter, Chad Day, told of a 10-year-old girl who spent a week behind bars for violating a judge’s order, and a 12-year-old boy who likewise committed no crime, but was nonetheless locked up for a month in detention alongside older boys accused of rape, first-degree battery and other felonies.

Then this April, the state’s juvenile corrections director abruptly resigned just days after getting blasted in the press for suggesting the state should limit commitments to youth adjudicated for felonies, as they do in Texas, California, Virginia, Ohio and other states. The details on this resignation are murky — the official reportedly owed a vast sum in back taxes, and he was not highly regarded by many in the juvenile justice community. But his departure — the latest in the longstanding revolving door at the top of Arkansas’ Division of Youth Services — has left the state’s already troubled youth corrections agency more rudderless than ever.

The flurry of negative news is all the more striking because, just a few years ago, Arkansas seemed on the road to reforming its system. The state published a strategic plan in 2009 committing itself to a fundamental shift away from excessive confinement and toward greater use of effective community-based services for court-involved youth. For several years the state was implementing that plan and was reportedly making tangible progress — enough to convince a JJIE reporter to write an article in April 2012 asking the question: “Arkansas Juvenile Justice Reform: A Blueprint for National Success?”

Not so much, it turns out.

But what lies behind all the recent bad news in Arkansas? And what does the state’s predicament suggest for the national movement to discard jingoistic get-tough orthodoxy, adapt practices in light of brain science and other new evidence, and embrace new and more humane approaches to adolescent misbehavior?

Dick Mendel

Recently I set out to study those questions. I read everything I could find about the Arkansas juvenile justice system, and I reached out to several juvenile justice officials and advocates in Arkansas — and to outside experts with close ties to the state. No simple answers emerged from my inquiry. But I walked away with five conclusions.

- First, Arkansas’ backsliding on juvenile justice wasn’t inevitable: In fact, the state really was making impressive strides toward reform for several years.

- This reform movement ran aground in 2013, thwarted by an idiosyncratic feature of Arkansas’ system — a politically powerful cabal of nonprofit service providers that has acquired monopoly over juvenile services statewide.

- This cabal has also helped perpetuate two signature weaknesses in the state’s juvenile system — a striking dearth of data collection and analysis, and an ongoing leadership gap at the state’s juvenile corrections agency.

- Despite these deep and continuing problems, momentum toward reform is once again mounting in Arkansas — much of it coming from the bottom up.

- As best as I can tell, the irresistible logic of reform and the good will of hardworking leaders in the state — especially judges — are likely to begin winning the day sometime in the not too distant future.

An overdue period of progress 2007-13

As incoming Gov. Mike Beebe assumed office in 2007, the Arkansas Division of Youth Services, the state’s youth corrections agency, could only be described as a train wreck.

Nine years earlier, the Arkansas-Democrat Gazette ran a five-part series revealing that youth in the state’s juvenile facilities were “routinely degraded; verbally, physically and sexually abused; hogtied; forced to sleep outside in freezing weather.” In 2002, a U.S. Department of Justice investigation of Arkansas’s largest youth prison, the Alexander Youth Services Center, found that while violent abuses had abated, the facility still failed to provide constitutionally required safety and rehabilitative care, mental health and educational services, suicide prevention, fire safety or religious freedom.

In 2006, the state’s Health and Human Services Department revealed that staff at Alexander “were drugging youths to control unruly behavior — in many cases without doctors’ orders.” Then in 2007, Arkansas’ Disability Rights Center and the National Center for Youth Law reported that facility staff were placing youth in solitary confinement arbitrarily, without protecting their due process rights or ensuring their safety.

Doubly troubling was the fact that the vast majority of youth confined in Arkansas facilities and subjected to these abusive conditions were not serious or violent offenders. In 2007, just 15 percent of the youth committed to state custody had committed a serious violent felony, while 42 percent had committed only misdemeanors.

Patricia Arthur

Patricia Arthur, then an attorney with the National Center for Youth Law, was preparing a lawsuit to challenge the persistent unconstitutional conditions at Alexander. The lawsuit threatened to embroil the state in years of costly and cumbersome litigation.

After 20 years in the Arkansas legislature and four years as attorney general, Beebe understood the juvenile justice challenge, and he decided quickly to improve the state’s youth corrections system rather than fight a legal battle. The governor invited Arthur to work with his administration to develop a comprehensive statewide juvenile justice reform plan.

Beebe’s choice to lead the Division of Youth Services (DYS), Ron Angel, brought no academic training or experience in juvenile justice or youth development. He had spent his entire career working for the Veterans Administration. But Angel proved to be a skilled administrator and a determined reformer. He quickly took charge of a 50-member reform task force and forged a close partnership with Arthur. In June 2009, Angel released a five-year strategic plan designed to “revolutionize the juvenile justice system in Arkansas.”

In addition to overhauling the education program and improving conditions inside the Alexander facility, the plan’s main goals were to reduce the number of low-risk youth committed to state-funded residential facilities and expand the scope and quality of community programs.

So DYS began releasing data showing the commitment numbers for each judicial district, which Angel says sparked conversations among judges and even a little bit of competition among judges. He set a goal for each judicial district to reduce commitments by 20 percent per year. DYS revamped its contracts with private provider agencies and created an incentive fund to reward providers that worked with judges in their districts and met the commitment reduction goals.

DYS also began funding local providers to begin delivering best-practice treatment models like the Youth Advocate Program and Multisystemic Therapy. It began tapping the state’s database to conduct meaningful data analysis and determine characteristics and treatment needs of its client population. Angel convinced the Annie E. Casey Foundation to bring the Juvenile Detention Alternatives Initiative (JDAI) to two pilot counties in Arkansas, Finally, despite considerable resistance, Angel asked provider agencies to begin submitting detailed records on their clients and services.

DYS also began funding local providers to begin delivering best-practice treatment models like the Youth Advocate Program and Multisystemic Therapy. It began tapping the state’s database to conduct meaningful data analysis and determine characteristics and treatment needs of its client population. Angel convinced the Annie E. Casey Foundation to bring the Juvenile Detention Alternatives Initiative (JDAI) to two pilot counties in Arkansas, Finally, despite considerable resistance, Angel asked provider agencies to begin submitting detailed records on their clients and services.

These efforts made a difference. From 2007 to 2012, the number of youth committed to state custody fell from 622 to 496, a drop of 20 percent.

A provider buzzsaw

Improvements were also recorded on other key indicators, but the pace of progress was modest: Compared with fiscal year 2007, five years later the average population in state youth facilities was down — but only by 12 percent. The share of committed youth adjudicated for misdemeanor offenses was down, but still comprised 35 percent of all commitments. Angel had closed 43 beds at the state’s Alexander facility (a 30 percent drop), but had not been able to close or reduce capacity at any of the seven smaller youth corrections facilities funded by DYS around the state.

Eager to accelerate progress, Angel and his allies crafted a new reform bill before the 2013 session of the state legislature. Called the Close to Home Act, the bill sought to engage entire communities, not just the service providers, in determining the right mix of programs and services for court-involved youth. Specifically, the bill called for the creation of local Community Youth Services Boards that would be responsible for cataloguing currently available services, identifying additional services to address unmet needs and allocating state funds to optimize services and minimize correctional placements.

Angel expected the legislation to pass. First, because he considered the proposal quite modest: The legislation called for community boards to be created in only five pilot jurisdictions. So if the new approach didn’t work, it could easily be scrapped before going statewide. Second, because Angel had the support of most juvenile judges in the state and the governor, whose party controlled a majority in both chambers of the state legislature.

But Angel’s optimism proved unfounded. Within weeks, the plan lay stillborn on the statehouse floor, throttled by a key sector of the system — its network of local private provider agencies.

Most of these provider agencies were created in the 1970s, sparked by the passage of the Runaway Youth Act in 1974 , which began making federal funds available for programs to assist homeless and runaway youth. Initially, these organizations struggled. But that began to change in the late 1970s and early ‘80s, when the providers got training on how their organizations could band together to expand their influence with state government.

In retrospect, the training worked too well. The provider agencies built strong boards, populating them with politically connected leaders in their communities, and they branched out to serve youth in the delinquency system in addition to homeless and runaway youth. The providers formed a new organization, the Arkansas Youth Service Providers Association, through which they gradually secured stable funding.

Rather than fight each other for contracts, the 13 participating providers agreed to carve up the state. Over time, each became the sole recipient of contracts with DYS to work with court-involved youth in its given territory. Through their association, the providers negotiated standard contracts with DYS to pay them for community-based services they provided. Some of the providers received multimillion-dollar contracts to operate residential corrections facilities as well.

Paul Kelly

Though no one I spoke with accused the provider group of corruption, or even bad will, several observers noted that the provider group has become a major impediment roadblock to reform in Arkansas. “The providers have become very entrenched in their position in the state,” explained Paul Kelly, who once ran a provider agency and served as the first director of the providers association. They very seldom have anyone competing with them for contracts, he added.

“They’ve learned to use their political influence and their relationships with community leaders to exert pressure on DYS to fix things they want fixed,” added Kelly, who now works at the Arkansas Advocates for Children and Families. The providers grew to fiercely oppose “any really meaningful accountability for the impact of their services,” he said.

Mickey Yeager, who spent five years as a data analyst at DYS before leaving in 2014, put it even more starkly: “The providers in Arkansas are very powerful. They basically do what they want.”

And in 2013, the providers wanted badly to kill Angel’s Close to Home Act. So they did. They worked their contacts in the legislature, mounted a fierce lobbying campaign and vanquished the bill.

The director of one provider organization, John Furness of Comprehensive Juvenile Services in Fort Smith, is unapologetic about the 2013 legislative battle. “I saw that as a complete dismantling of the very established provider network that has been in place for many years and does good work,” Furness told me. “I thought it was a bad bill, and we spoke out against it. And it didn’t pass.”

Within weeks, the 66-year-old Angel tendered his resignation and retired.

Perpetuating problems

The providers’ role in killing the 2013 reform legislation was exceptional — a high-stakes, in-your-face power struggle. But as several observers pointed out to me, the outsized influence of the provider association also shows up in more subtle ways, with pernicious and lasting effects.

When you look closely at the long arc of juvenile justice in Arkansas, two weaknesses emerge front and center: a striking dearth of accurate data and meaningful data analysis; and continuing turnover in the leadership of DYS. In both cases, the providers’ fingerprints are hard to miss.

Probably the most glaring illustration of such data deficiencies comes from Chad Day, the reporter. DYS data indicated that 1,078 status offenders were detained in Arkansas in 2014, among the highest totals in the nation.

But when Day began interviewing local officials, he discovered this figure was wildly off-base. Even after personally examining the logs of all 14 detention centers statewide, he could not say precisely how many status offenders were detained — concluding only that “status offenders entered youth lockups more than 500 times” during the year.

When Judge Leigh Zuerker took over as Sebastian County’s juvenile court judge in early 2015, she said DYS figures that indicated status offenders were detained 449 times during 2014 were bogus. She personally reviewed the county’s detention records, she said, and found that the true number of status offenders detained in 2014 was 78 — less than one-fifth the reported total.

DYS’ failure to compile reliable detention data is perhaps understandable given its lack of direct authority over the detention centers, which are county-run. But the agency also lacks information about and analysis of its own programs. Here, the providers have played a decisive role.

Prior to 2007, DYS made little effort to analyze its population, assess their needs, determine what worked and what didn’t, measure recidivism in any meaningful way or identify the factors that led some youth to succeed in rehabilitation while others failed. The state did collect data on young people’s backgrounds, Angel told me, and the information was available in the state’s computer database.

“I had two staff members who did nothing but mine that data.” he said. But historically, he explained, “there’s hasn’t been enough mining into the data internally to pull those numbers out to use on behalf of improvement in the state.”

Angel had tried to expand the available data by requiring service providers to start reporting details on the services they provided, and their results during his tenure. “We tried to implement performance [measures],” he recalled, “and you would have thought we had asked for their first-born child.

“They said they didn’t have time, they didn’t get paid enough. There were a lot of reasons why they didn’t want to do it,” Angel said. “How can you base your treatment if you don’t have standards where you can measure what’s being successful and what’s not?”

Mickey Yeager, the data and quality assurance specialist, told me that “Before I came in, no one was looking at the data. The data was there, you just had to pull it. But no one was digging through it.” As Angel began pushing for more data, Yeager said, the providers “fought us every step of the way.”

And they had powerful friends in the legislature, Yeager recalled: “Ron was called to the capital several times ... because he was trying to track the performance of the providers, and they really didn’t like that.”

This dynamic is anything but new, said Paul Kelly, the first provider association director, and it helps explain the almost continuous turnover at DYS over the past two decades. “I have sat back and watched [the providers] make life miserable for one DYS director after another, just because they propose a different way of doing things or make life in any way uncomfortable,” he said.

Indeed, looking back on Angel’s tenure, perhaps his most striking accomplishment is that he lasted six years. When Angel was hired, he came as the agency’s ninth new director in 12 years. In the three years since his retirement, DYS has cycled through two more directors, with a third — an interim hire — named in mid-July.

“[The providers] have been in large part responsible for the turnover in DYS directors,” Kelly said. “They have that capacity.”

Renewed momentum

Despite these continuing problems, a scan of the state today reveals that momentum for reform seems to be building once again. This time, however, it is not being led by a singular leader like Ron Angel and it does not involve any coordinated statewide plan. Rather, the momentum represents the confluence of several promising developments, many of them taking place at the local level.

For instance, both of the state’s two pilot JDAI sites — Benton County and Washington County — reduced detention admissions by 30 percent in their first year, and both reduced total detention days by a similar margin. As part of JDAI, both counties introduced risk assessment instruments to guide detention admissions, and both expanded alternative to detention programs. In addition, Washington County embraced new probation practices to better engage with young people’s families and to reduce unnecessary confinement due to probation violations.

Gina Vincent

Meanwhile, four other counties have joined an initiative to introduce and make use of state-of-the-art risk and needs assessments for court-involved youth. Gina Vincent, the University of Massachusetts expert who directs the project, reports that the counties are making progress, and that “there’s been very good buy-in” from judges. As part of the effort, Vincent and her team are helping the counties develop a continuum of services to address needs identified in the assessment, relying on resources throughout the participating jurisdictions — not just the designated DYS service providers. The state’s Administrative Office of the Courts is playing a central role in the project, and has identified eight additional counties that will join the project later in 2016, with plans for even more counties next year.

Helping fill the leadership void at DYS, the Administrative Office of the Courts is also taking a lead role in efforts to improve data collection in the juvenile system, and is participating in an active new juvenile justice reform subcommittee sponsored by the Arkansas Supreme Court. That committee has also reached agreement with the RFK National Resource Center for Juvenile Justice to review the probation systems in two urban counties and a rural judicial district.

Meanwhile, a youth justice reform board appointed last year by Gov. Asa Hutchison has been deliberating, and it appears ready to advocate a multimillion-dollar confinement reduction fund, reviving Ron Angel’s reform strategy, as well as an expansion of JDAI, consistent use of objective risk and needs assessments, and stronger data collection and dissemination.

But maybe the most encouraging trend can be seen among the state’s juvenile judges. Historically, many judges have maintained an old-school, law-and-order approach toward youth in the justice system — clinging to their prerogatives to jail low-risk youth, even status offenders, who defy their orders. Arkansas judges have also retained the right to place court-involved youth into detention for up to 90 days — even status offenders. And some Arkansas juvenile judges still believe they should retain these rights.

Yet, more and more judges are shifting away from this orthodoxy, embracing more therapeutic and targeted intervention strategies. For instance, when he first came to the bench, Judge Wiley Branton in Pulaski County (Little Rock) regularly sent low-level youth offenders to detention. But Branton last year told the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette that he hadn’t detained a status offender in at least five years. “I’ve gotten over myself as a judge, which is a hard thing to do sometimes,” he said. “So I can now accept the fact that a kid might willfully disobey my order, and it won’t necessarily get me bent out of shape. If it’s [a status offender], I’m not going to open up my detention facility.”

Judge Stacey Zimmerman

Judge Stacey Zimmerman has spent nearly two decades on the juvenile bench in Washington County, and until recently she didn’t hesitate to throw young people into detention for defying her authority. Chad Day reported that Zimmerman detained 51 status offenders in 2014, but only six during the first six months of 2015. In a phone call, she described having a “light bulb moment” while visiting a model JDAI site in Santa Cruz, California.

“When I went to those programs, and talked with the people in the trenches, I really bought in,” the judge recalled. “I am still all for consequences, it’s just that I’m learning to be more creative and finding ways to give consequences without putting Junior into lock-up.”

Before he retired at the end of 2014 after nearly 30 years as the juvenile judge in Sebastian County, Chad Day reported, Judge Mark Hewett “used his contempt power to detain hundreds of children for not following his orders to attend school.” Hewett was succeeded last year by former public defender Leigh Zuerker.

In a phone interview, Zuerker declined to criticize Hewett, but she did say she has worked to reduce status offender detentions, and reported that she had in fact cut the number of status offenders detained in the county from 78 in 2014 to 38 in 2015. Under Zuerker, Sebastian County has also introduced a new trauma-informed counseling program to assist court-involved youth and their families.

Zuerker also reported that she is not alone in seeking to cut the number of status offenders locked in detention. She has spoken several times with judges in two other counties where status offenders are reportedly still detained in high numbers. “I know they are doing everything they can to bring those numbers down,” she said. “We’ve talked about it and brainstormed.”

An optimistic forecast

During our recent phone call, Angel recalled the very clear message he received at the outset of his tenure at DYS in conversations with the provider group. “They told me: They have been here for 30 years, the same provider group, and they knew what was needed, and there was nothing that could be brought in that would work any better than what they were doing at the time.”

The providers stuck to that sentiment throughout Angel’s tenure, and ultimately managed to defeat him.

Yet, it is difficult to imagine this line will hold much longer in Arkansas, given the breadth of reform efforts now underway in the state’s juvenile court system and the noticeable shift in judicial philosophy taking root across the state.

The juvenile justice field has made dramatic advances in recent times, both in research and practice, and a wealth of data has emerged demonstrating that research-informed community-based programming yields far better results than the confinement-heavy, seat-of-the-pants approach of yesteryear.

Across the state, judges and other local leaders are growing more and more familiar with, more and more comfortable with, more and more eager to embrace what works — as their peers have done in states throughout the nation.

In the face of this groundswell, the providers will face increasing pressure to adapt new practices, to begin collecting and reporting data, and measuring their impact. If they continue to resist — if providers maintain their insistence on standing still, and that that they know best, and that the old ways are still best — they will likely squander their remaining credibility and lose their cherished place at the heart of the Arkansas system.

The pull of progress is simply too strong.

This story has been updated.

look wake the hell up and see what is going on with this state. we are communists. it’s a sad reality of taking children and selling them. I am a victim of dependency neglect. my daughter has been kidnapped by judge branton and I’m told just to pretend that my child never existed. it’s a sad day for everyone who thinks of garretts law as a “great” thing, because unfortunately dcfs fucked wiyh the wrong one.

As you can see from the rapid responses from the Arkansas provider community, they believe they are doing a great job. I did not see this article as being negative towards the people who are providing services to the youth? This article was specifically directed toward systemic problems that exist within the Arkansas juvenile justice system.

During my tenure as Director of Arkansas DYS I was fortunate to have met many of the direct care staff. They are truly talented, dedicated and hard working professionals. I have a great deal of respect for all of the men and women who work directly with the youth. I also have a deep respect for the many juvenile judges of this state. They work long and often frustrating hours trying to come up with a plan to save many of the youth they see from going deeper into the system. A number of the judges said they were frustrated because of the lack of treatment options to avoid incarcerating the youth.

The author’s point in this article is right on target. His assertion that much of the problems is caused by resistance to change. When you look at the charts embedded in his article, it becomes evident that something is wrong because NUMBERS DO NOT LIE. Surrounding states have overhauled their system and it is obvious they are experiencing tremendous successes in preventing youth from unnecessary incarceration. Seeing these numbers, one must ask, “Why is Arkansas going the opposite direction”?

The answer to part of the problem is that some share holders continue to fight change. A simple analogy is like taking a typewriter that was made in 1970 and challenging a person with a modern computer to a timed essay contest. There is no question who will win.

Money is another factor in the equation. Without shifting old money and adding some new money, change will be difficult. Continuing to put money into old programs that worked in the 70’s, 80’s, and 90’s, will not get near the positive outcomes as shifting money to new programs that are currently found to be proven best practices today. There are some people who says give me more money but don’t tell how to use it. That is not the answer to fixing the existing problems.

One respondent to this article charcterized myself and the other state employee mentioned in this article as disgruntled state employees. That could not be farthest from the truth. We both had retired from previous successful careers and had come to work in DYS because we thought we could help young people move past their errors and be successful. I took the position even tho I was warned by high level managers about how dysfunctional some aspects were. I erroneously thought we could all set down at the table, talk about what we were doing right and what could be done better based on data and studies of new and innovative programs in other states. Much to my disappointment, that never happened. I personally left because I didn’t want to be a part of a system that certain elements fought so ardently and regrettably, successfully not to change. I was there to help kids, not draw a salary.

The article does give me reason for hope. I am happy to see that forward thinking judges and other organizations are working together from the “grass roots” level to initiate changes that are benefitting youth. Many of the judges I had worked with often stated that they were anxious to be given the opportunity to have input into programs tailored to their specific needs. Some judges voiced frustration that they had been informed that the services offered was all that was available. Anyway, I cheer for those who are taking matters into their own hands to make change happen.

Finally, Arkansas is blessed to have had former Governor Mike Beebe and current Governor Asa Hutchinson. Both men have always been strong advocates for the youth of this state. I just hope Governor Hutchinson and legislators will start asking some pointed pointed questions during the upcoming legislative session? Hopefully people quit listening to others say how good they are and start asking them to prove it.

Please help these at risk youth. They all need you to care about thei future.

What specific service providers are using what specific outdated–according to you–practices in lieu of what specific evidence-based “best practices”? I work every day in my current successful career helping children for an Arkansas CBP and I am an also ardent advocate for reform in the juvenile justice system. I would genuinely like to know exactly more of what you are referring to above in your response as someone who continues to work in the field in this state, no matter how frustrating and infuriating it can be. I don’t and won’t jump ship.

Ron Angel – I’d love to chat with you sometime about your experiences and any thoughts you have. Please send email. http://www.cla.auburn.edu/psychology/people/professorial-faculty/jan-newman/

I have served for the past 36 years as Executive Director of Consolidated Youth Services, a non-profit youth service provider. There are so many inaccuracies in this article I hardly know where to begin. Most importantly it is obvious that the author made no attempt to determine the accuracy of his article. First, service areas were initially established in 1981 when Arkansas Department of Human Services issued an RFP for statewide youth services. This was not the action of providers “carving up the state”. In fact, this meant service providers could not just choose to serve well-populated areas of the state and ignore troubled youth in rural areas of the state. The service areas have been changed several times by the State and each time DYS issued a Request for Proposals (RFP). Any person, nonprofit, or for profit entity is free to submit a bid on the RFP. Current Providers have no monopoly on the State contracts, and in fact new providers have secured contacts in some areas as a result of the RFP process. The reason DYS established geographic service areas in 1981 was to assure that every county of the state had a youth service provider to provide the court with alternative services to prevent incarceration of youth in every part of the state. Second, Providers have constantly supported the effort to track outcomes of youth served. As far back to 1985, Providers have submitted Client Performance Outcomes data to DYS at intake, closure, and six months follow up. For years, before computerized data entry was possible, Providers submitted this data in paper form to DYS monthly and DYS employees were to enter this data into their data system. Finally in the early 1990’s DYS simply told providers to quit sending it to them because the data was not being entered into the system and was sitting in boxes. In the late 1990’s when the state computerized its data entry and providers were able to enter intake and billing data into the database, DYS did not activate the outcome data collection component. However, many Providers continued to collect the data individually. When the State finally initiated the use of the outcome data component of the online system, Providers were immediately supportive of this data collection contrary to what Mickey Yeager and Ron Angel have stated. Providers have entered and continue to enter intake, closure, and follow up data on each youth served. This data includes how the youth are functioning in family, school, legal system, employment, mental health, and drug usage. The issue is that, although the data is entered, DYS IT capabilities cannot produce any meaningful reports. To this day, Providers continue to enter this data and to this day DYS has not been able to generate the needed reports. For over 5 years, there have been almost monthly meetings with DYS over this issue and Providers have continually asked that DYS work to overcome this IT issue. These meetings are well documented and representatives of more than one governor and Paul Kelly have been present at these meetings. I do not believe there is anyone at DYS who could refute the fact that Providers have worked tirelessly trying to get DYS to fix the IT situation so reports can be generated from the performance data we submit. Third, Mendel accurately reported that commitments fell by 20% in 2012. The fact is, this was accomplished because the State used federal stimulus money to increase funding to the very providers that Mendel has demonized in this article. The stimulus funding ($2.5 million statewide) was not huge compared to the amount of money many states have poured into community based services to effect a reduction in commitments. The funding covered all 75 counties and thus averaged only $33,000 per county (barely more than the cost of 1 commitment to DYS). Ron Angel was able to cut the 43 beds at the largest DYS facility because increased Provider services reduced commitments by the 20%. The cost of each bed was over $240 per day. Where did DYS use this cost savings? Angel and others at DHS had promised legislators and providers that money saved from the reduction in beds would replace the stimulus money and thus would continue to fund the services that were initiated. The fact is, the stimulus money was never replaced with the saving generated from the reduced beds and community based funding has decreased by the $2.5 million and has now returned to the funding level it was in 2006 when minimum wage was $5.15. Angel never offered any acceptable explanation to legislators of how 43 beds were reduced yet there was no savings to continue funding the services started with the Federal money as they had promised. Finally, in 2013 the reform movement which was thwarted was an attempt by Ron Angel to eliminate any funding of services based on a service area. Statewide funding based on any type of formula would have been eliminated. Instead, DYS would be able to pick and choose how much money was allocated for each service “recommended” by community boards. There would have been no assurance that every rural area of the state would have any services. DYS Director, Ron Angel would have had ultimate control of all community based program funding and no longer would the $16 million be distributed across the state to all 75 counties based on a formula primarily using youth population with some adjustment for poverty und community based services. Legislators were already upset with Angel because DYS had not used the cost saving from reduced beds as promised to assure continued funding of services in their communities. This is what thwarted the legislation supported by Ron Angel, advocates located in Little Rock, and out of state “experts”. The plan was not supported by Judges, juvenile staff, or others in the community and legislators agreed this was a bad idea and the effort failed.

I hope all who read this article will take the time to discover the truth about Juvenile Justice in Arkansas. In the meantime, youth service providers will continue to advocate for community based funding of intervention services which will keep youth “close to home” and prevent unnecessary incarceration.

Hear, heat! Thank you, Bonnie.

Hear, HEAR rather, Bonnie!

As a 7 year employee of one of the Arkansas DYS-contracted Community Based Service Providers as a LCSW providing mental health/substance abuse treatment to youth at risk of – or involved in the juvenile justice system, this story is appalling, inaccurate, full of specious information that is reliant on personal–and mind-bafflingly wrong–grousing of a couple of former state employees and selected quotes from one or two other sources. It is written with a complete lack of balance or fairness to the work that is done by the people who work alongside me and the kids we are also physically beside every single day.

Since day one in my position, it has been ingrained into me that youth need effective, evidence-based treatment and other services provided in the community if at all possible and to advocate with the juvenile court to first order these services which have been proven to more effective than incarceration. Also, I have absolutely no idea what this “CBPs are abjectly resistant to data-driven processes” nonsense mentioned by the former DYS employees is about because, on behalf of DYS using the various forms they’ve approved for statewide collection, I–along with all of my coworkers–have collected macro/micro level data at intake/discharge/6 month follow up points with every client that has been regularly submitted to DYS since I accepted my first case!

I could go on but I think it would be best if instead, you, Dick Mendel, went on and completed a follow-up to this piece that indicated a true desire to investigate and report. There are plenty more sources to investigate to flesh out a more accurate portrayal of juvenile justice as a whole in this state and oh yes, that story needs writing. And if you take on my challenge, please resist that damaging urge to wrap up something into a nice little neat ball of negativity and misplaced blame. The kids you claim to be concerned about will likely be all the better for it.

As the newly elected President of the Arkansas Youth Service Provider’s Association I take exception to the entire tone and content of this article. Youth Service Providers have personally spent hours and hours drafting Arkansas Youth Justice Reform Recommendations and promoting collaboration among all parties. In fact we are recently making some significant headway FINALLY in youth justice reform in Arkansas. This article is not only poor journalism. It is negative, cynical, poorly researched and and it is absolutely NOT in the best interest of working toward collaborative solutions for youth. As further evidence of this I also submit the following excerpt from an email I just received from Paul Kelly who was quoted throughout this article:

“I want to voice my strong objection to the selected use of quotes attributed to me by Dick Mendel in his recent article. I was not able to review the article prior to its publication.

I emphasized that it was important for him to explain that no single party has been to blame for the lack of progress on juvenile justice reform. His reply was that that way of telling the story was “too nuanced.” Mr. Mendel chose instead to wrongfully single out Arkansas youth service providers as the sole reason for problems and the state’s failure to make progress.

During interviews, I had defended service providers, their passion for their work and the many barriers they faced with judges, administration, and legislators. In particular, I dispelled the notion that service providers were resistant to recommendations championed by the Governor’s Youth Justice Reform Board; in fact, they are fully on board with proposed changes.

I sincerely regret my part in creating this unfortunate characterization of Arkansas. I certainly share Mr. Mendel’s frustration with the lack of progress with youth justice reform in Arkansas, but he did not fairly depict the work being done now and the providers’ engagement and critical role in positive change.”

Paul D. Kelly

Senior Policy Analyst

Arkansas Advocates for Children and Families

The discussion of the provider role in jj reform is on point. Of the states I work (ed) with over the last six years provider relation are a considerable factor in the equation for getting sustainable reform. The fininacial dependency of providers is a constant. The desire for the provider ageny to grow their business an organizational dynamic grounded in systems theory that when a system stops growing atrophy sets in. Provider agencies have struggled with the shift in referral pattern toward high risk youth The resistance to basic data reporting and more rigorous quality assurance is grounded in fear of the outcomes as well as the administrative costs. Grounding data collection in a hold harmless quality assurance system is one answer. State agencies must also be willing to renegotiate rate agreements that compensate providers for the increased intensity of rehabilitative interventions and the administrative cost burden of QA/QI.

Two constants in my work are the need for judicial education and provider engagement in the reform effort. Instead of us and them conversations let’s recognize that there are no others.