ACLU

.

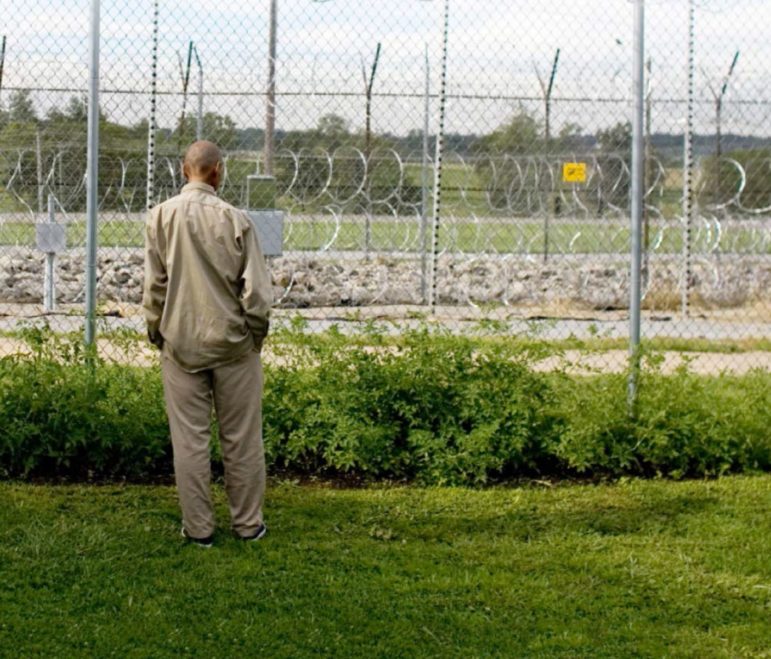

In the wake of Supreme Court decisions that have limited extreme sentences for juveniles, states are relying on parole boards to put those rulings into effect.

But those boards operate with little transparency, rarely focus on how a prisoner has changed while serving their time and ultimately seldom grant parole to serious offenders, the ACLU researchers said.

“It’s wonderful there is attention on making sure juveniles and other young people aren’t going to die in prison, but all the responsibilities for making sure they do get released are in the backwater of parole,” said Sarah Mehta, the lead author of the report.

For more information about juvenile indigent defense, go to JJIE Resource Hub | Juvenile Indigent Defense

The researchers investigated parole systems across the country, including interviews with 124 prisoners who were between the ages of 12 and 26 when they committed serious crimes.

They found that in 12 states, more than 8,300 prisoners are serving sentences of parolable life, or at least 40 years, for crimes they committed as juveniles. Thousands more who committed crimes in their late teens or early 20s also have been sentenced to life with the possibility of parole.

The report details the staggering caseloads of many parole boards — as many as thousands per month — and the limited opportunities for prisoners to make their case for release.

Carol Howes, who retired in 2012 after 27 years as a warden in Michigan prisons, said prisoners’ narrow chance at parole left them feeling helpless after they believed they had turned their lives around in prison. When prisoners returned from an unsuccessful parole hearing, they had usually heard nothing about what they could do to further prove their rehabilitation, she said.

“The parole board was saying all you can do is more time,” said Howes, who has advocated for individual prisoners and for parole reforms in Michigan. “It had an effect on not just the prisoners but the whole facility, because it was so demoralizing. I would find it quite frustrating when I would make my rounds and they would ask, ‘What can I do? What else I can do?’”

A mitigating factor

Mehta said parole boards tend to focus heavily on a prisoner’s original crime — which an offender cannot change — rather than what they’ve done since to prove they have grown and changed. And, when their youth at the time of a crime is considered, it can be seen as an aggravating factor, rather than a mitigating one as intended by the Supreme Court, she added.

That last factor points to the need for officials who understand adolescent development and how it is relevant to the decisions they make, the researchers said. In addition, they called for reforms including:

- further limits on extreme sentencing, such as setting parole eligibility no more than 10 years after young offenders serving 20 or more years come into custody;

- increased efficacy, transparency and fairness in the parole system, such as presumptive eligibility for parole unless the state proves a person needs to remain in prison, in-person hearings and better data collection; and

- expanded and improved rehabilitation and reentry programs to ensure prisoners’ success if they do leave prison.

Mehta said some states, including Nevada, Connecticut and California, are making progress on meaningful opportunities for parole for young offenders.

“There is some hope. I think the question is what is this going to look like in practice or is it going to be lip service,” she said.

Heather Renwick, legal director of the Campaign for the Fair Sentencing of Youth, said the report offers a valuable snapshot of how parole boards currently operate.

States are in the earliest stages of how to implement the Supreme Court rulings that banned mandatory life without parole for juveniles, she said. Thus officials, including at parole boards, are still learning what it means to truly consider an offender’s youth in sentencing, she said.

Renwick said she’s hopeful states will move away from considering a youth an aggravating factor and toward a fuller understanding of adolescent development.

“We’ve seen a lot of momentum to more age-appropriate sentencing on the front end and now boards are thinking about how to do it on the back end,” she said.

Wanted to drop a remark and let you know your Rss feed isnt working today. I tried inndluicg it to my Google reader account but got nothing.

George Bernard Shaw is credited with the quote: “To Punish a Man, You must Injure him; To Reform a man, you must Improve him; and men are Not Improved by Injuries.” It may prove helpful to examine how many states return ‘Youthful Offenders’ who violate parole to the ‘nearest institution’-such as was noted at Attica in 1971, and to examine the lack of resources to help those not yet released on parole to locate and obtain gainful employment which was a prerequisite for Parole Eligibility in New York at that time, rather than making suitable referrals to Vocational Rehabilitation programs, and using ACE score criteria for undiagnosed ‘challenges’–(from the US CDC/Kaiser-Permenente ACE [Adverse Childhood Experiences] Study–as Vocational Rehabilitation counselors in Iceland are now doing.). It may also help to examine the “Arbitrary and Capricious Abuse of Administrative Authority” of both Parole Boards, and Individual Parole Officers.

It would be great if the ACLU chapter in Georgia would take an investigative search into why there are over an hundred men and women in Georgia prisons that have been incarcerated for over 20 and 30 plus years sentenced to Life with the possibility for parole for crimes committed between the ages of 13 and 16 that after two and three decades lanquishing in prison have yet to be granted parole. Prior to 1995 Life with parole was 7 years to serve before becoming eligible for parole consideration. Between 1995 and 2006 parole eligibilty went up to 14 years. In 2006 the law mandated that parole eligibilty was after serving 30 years. The hundreds of men and women in Georgia prisons that were juveniles ages 13 and 16 were sentenced under the 7 and 14 years parole eligibility statue. Yet the Georgia Parole Boards continously denies parole for intravals for up to 1 to 8 years for the next consideration citing a Georgia statue O.C.G.A. 42-9-42(c) NOT COMPATIBLE TO THE WELFARE OF SOCIETY DUE TO THE NATURE OF OFFENSIVE.