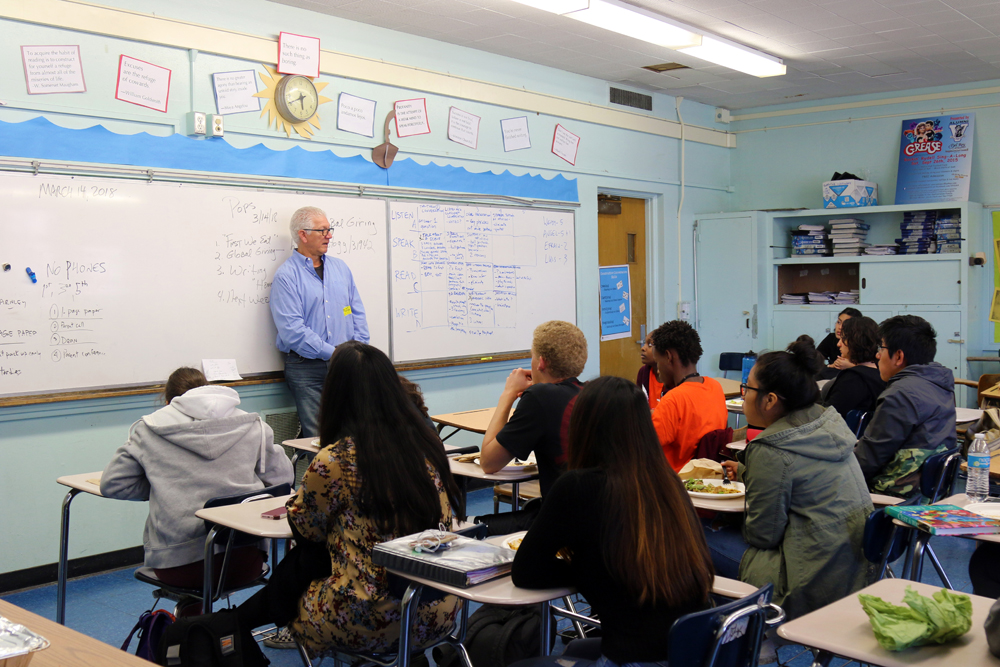

It’s lunchtime on a recent Wednesday at Venice High School. Twenty or so students are sitting at their desks with full plates of food looking up at the teacher. No one is looking at their phones. They listen attentively to the man up front, who is giving them a writing prompt.

The man is actually a retired teacher, a 20-plus-year veteran of the Los Angeles Unified School District, who volunteers once a week in this classroom. The students show up weekly to discuss, write, read aloud what they have written and share their thoughts in other ways; not because they have to, but because of their one unique commonality.

They are the sons and daughters, nephews and nieces, grandsons and granddaughters of prison inmates. Of the nearly 2.3 million people in prison in the United States, 52 percent of state inmates and 63 percent of federal inmates are the parents of minor children. Put another way, according to Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2.3 percent of the U.S. population under 18 have a parent or parents in prison. Those kids, like these students, are left with the shame and stigma of loving someone on the inside.

amyfriedman.net

Amy Friedman

POPS the Club, the Los Angeles-based organization that is sponsoring the noon meeting, works to battle against this stigma and to create a safe space for students with incarcerated family. POPS, short for “pain of the prison system,” was launched in February 2013 by editor and author Amy Friedman and her husband Dennis Danziger, a novelist, playwright — and the man at the front of the classroom giving the writing prompts and facilitating the open discussions.

POPS started at Venice High and since has spread to eight high schools in the Los Angeles area plus schools on the East Coast and pilot clubs in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, and Baltimore. Each club aims to create a home and sense of community for students to meet weekly to share a meal and their stories through discussion, writing, art and mindfulness exercises.

It’s personal

Friedman’s ties to the prison system are personal. More than 25 years ago, she was a newspaper columnist in Kingston, Ontario, Canada, and decided she wanted to learn more about how prisons worked. She started visiting Kingston’s Joyceville Penitentiary with the intention of writing a series of articles about the facility. In the midst of her reporting, something unusual happened. “I wound up falling in love with a man who was in prison, marrying him, and his daughters moved in with me,” she said.

The girls were 3 and 7 years old when their father went to prison. As Friedman got to know them, she was extremely troubled by the shame and emotional burdens her new step-daughters were forced to carry. “It upset me. It infuriated me,” she said. “My experience of being a prisoner’s wife shaped my understanding of how people who love people in prison are treated as if somehow they are a criminal, and that crime is loving someone who is inside.”

The girls were 3 and 7 years old when their father went to prison. As Friedman got to know them, she was extremely troubled by the shame and emotional burdens her new step-daughters were forced to carry. “It upset me. It infuriated me,” she said. “My experience of being a prisoner’s wife shaped my understanding of how people who love people in prison are treated as if somehow they are a criminal, and that crime is loving someone who is inside.”

Although Friedman and her Canadian husband eventually divorced, his daughters remain in her life. Friedman later remarried (to Danziger) and moved to Los Angeles where, as part of a program sponsored by the L.A. branch of PEN America, she taught creative writing in Danziger’s 10th- and 12th-grade classrooms at Palisades Charter High School and later Venice High School from the fall of 2005 through the spring of 2012.

As Friedman worked with students on their essays, she discovered that an unusual number had family or close friends in prison. But, as she had seen with her step-daughters, they never spoke of it. The couple decided to try to make an impact on this rarely recognized grouping of students.

The couple decided to model their new venture on the template of the LGBTQ school clubs, which had been instrumental in breaking down the stereotypes around being gay or transgender for students. Friedman and Danziger managed to track down the man who wrote the original proposal for such clubs. With his help, they borrowed and refashioned the model, then presented their proposal to launch a new student club to the Venice High School principal, who bought the idea right away, she said.

Shock and awe

Thus, the first POPS was born in February 2013. News spread mainly through word of mouth as Danziger told his classes about the new club and invited students to join the meetings.

Friedman and Danziger based the club on three basic rules. First, no one could be sent to POPS by a counselor, parent or teacher. Members were to attend meetings of their own volition. Second, since the club was scheduled to meet at lunchtime, POPS would always provide food, which they saw as symbolic of breaking bread and breaking down barriers. Third, the club was open to anyone with any sort of connection to incarceration, whether they had a loved one inside or had been locked-up themselves.

After the first POPS meeting, Friedman knew she was on the right path. She tells of watching a 10th-grade girl coming into the meeting room, choosing her peanut butter and jelly sandwich and sitting down. A few minutes later, a second 10th-grade girl walked in. Friedman watched as the two spotted each other from across the room, each visibly stunned by the other’s presence.

The girls had been good friends since kindergarten, but before coming to the POPS meeting, neither knew the other had an incarcerated father. “They’d shared all kinds of things,” Friedman said, “but never shared that.”

She remembers turning to her husband after watching their expressions of shock, then discovery. “We need to bring this to every high school in America,” she told him, then laughed when he rolled his eyes in mock horror at the prospect.

Since that day, expanding POPS has sometimes been an uphill climb, according to Friedman, but the vision of bringing the club to as many U.S. schools as possible remains.

POPS has been the scene of many success stories and positive steps forward for hundreds of young people. One such student is Daniel Ortiz, a young gang member who, in the beginning, talked at meetings of loving his hood and his gang. But as he continued to return to POPS, Ortiz began earning recognition from his classmates, friends and teachers for his writing and reading in class, Danziger said. And when Ortiz found his voice, the space that the gang had once occupied began to be filled by writing and rapping and visions of a different future.

Lauren Dunn

POPS always provides food, which they see as symbolic of breaking bread and breaking down barriers.

Filling the void

The issues, the stigmatization, the silence faced by these children tied to the prison system can have profound effects on them, Friedman said. The POPS curriculum is specifically designed to disrupt those stigmas and silences. In addition to the writing, mindfulness exercises, and experiments with various art forms, there are guest speakers. Some come to share information about scholarship opportunities and post-graduation programs to jumpstart the students to their next levels of schooling or the professional world. Other visitors, who have done their own time in California state prisons, come to talk about their painful past experiences with insight and eloquence.

Every club is run by a group of volunteers that includes a teacher or school-based sponsor, community-based volunteers and guest speakers. Thus, every club “has its own personality,” Friedman said. Some may lean mostly toward writing exercises, while other clubs may spend a higher percentage of time with talk and personal sharing during the meetings.

Danziger, who is the head volunteer for the Venice High School Club, spent one club meeting in March focused solely on writing. After all the students filled their plates with pasta, salad and rolls, he introduced several writing prompts.

He asked them to step outside their comfort zones and write about something they “typically would never want to write about, talk about or think about.” Finally, he asked the kids to write the name of someone they would trust enough to share this story with.

During the decades he taught high school English, Danziger spent a lot of time helping students write memoirs: “What we do in life is we tell each other stories.”

‘It just opens something up’

The couple sing the same tune, explaining that simply opening the floor for dialogue, providing a welcome place and a safe haven for everyone to gradually tell their hardest stories, has a deep impact on the POPS members.

“Basically, what it really is, is training people on how to create sacred space more than anything,” Friedman said. “It is about making the space safe enough for people to feel that they have a community and to feel that they can talk to each other.”

Over time, Friedman and Danziger realized that some kids were ready to have their stories heard by others outside the POPS world, and that they should be heard. The two began publishing an annual anthology of the students’ writing and artwork. The newest volume was launched Saturday, complete with a launch party, and like earlier POPS anthologies, it features startlingly moving tales of deep reflection and heartbreak.

“Once these kids are able to write their stories, it just opens something up in them,” Danziger said. “You cannot read this book straight through … you read four or five pages … you’re done and you wipe your eyes.” It is powerful, he said, to give the POPS kids an “opportunity to stop hiding.”

Friedman further illustrated the point with an experience she and Danziger had with a POPS graduate several months ago. The young man had a particularly difficult childhood that included multiple bouts of homelessness. Now he is 20 years old with a good job, she said.

Recently, however, he had to live in his car for a few months. During that time, he told his former mentors, his car was broken into and everything was stolen. He then said he wanted to ask for a favor. Friedman assumed he was going to ask to stay with her family or perhaps borrow some money. The real nature of the favor was entirely different.

“So … when everything was stolen,” he told them, “my POPS anthology was stolen that has my piece in it. I wondered if I could get another one. I wrote that piece and I stood up in front of the room and read it to everybody. That is the reason I’m OK today.”

Such moment convince Friedman and Danziger that POPS must be expanded. Since its inception, she said, the various clubs have affected an estimated 350 to 400 students. The number of POPS volunteers has grown to about 60. Next, in addition to the pilot clubs in Harrisburg, Baltimore, the organization has plans to launch more clubs in, Atlanta and New York City.

In the meantime, at Venice High School, every Wednesday at lunchtime, students who used to feel they had to hide a crucial part of their lives, have found a home and, more importantly, a voice in a club called POPS.

This story, part of a series by reporters from the USC Annenberg School of Communication and Journalism, is the product of a collaboration between the Juvenile Justice Information Exchange and WitnessLA.

Hello. We have a small favor to ask. Advertising revenues across the media are falling fast. You can see why we need to ask for your help. Our independent journalism on the juvenile justice system takes a lot of time, money and hard work to produce. But we believe it’s crucial — and we think you agree.

If everyone who reads our reporting helps to pay for it, our future would be much more secure. Every bit helps.

Thanks for listening.