The Youth Today/InsideOUT Writers series these past two years has been a critical reflection on the impact of the American justice system on our youth, how these youth learn to navigate through that system and the ways in which many of these youth nevertheless find ways to humanize themselves into healthy young adults.

In An Unspoken Voice, Marcos Nuñez told readers about the impact that reading had on his ability to place into perspective his long and testing sentence through ‘the belly of the beast’:

Nicole Barton

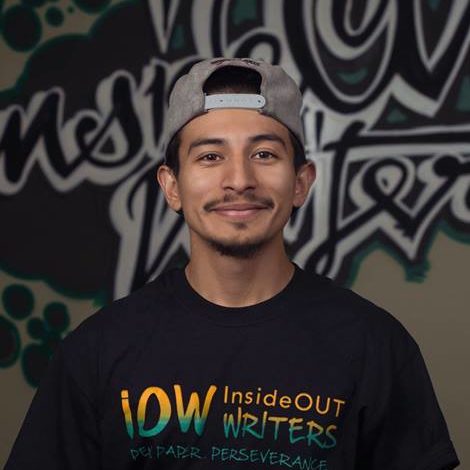

Jimmy Recinos

“My readings taught me that I valued loyalty, and as I did more reflecting, I began to see what else was important to me. There were changes to make … I had to take action.”

Marcos was a teenager when he was sentenced to five years in the California Youth Authority prison system, but reading proved vital toward his ability to discover more of himself beyond the environment he found himself in. And this would go the distance.

In Sailing through Memory, Daivion “Dee” Davis described the process of finding his way back to himself after years of fighting with an “inner darkness”:

“My mind is somewhat of a junkyard, full of twisted metal and lost souls, and I sweat as I run from demons that pose as guilty pleasures. My future looks close, yet far, like a regatta waiting for me at bay.”

Strengthened resilience

The process of turning learning into an action is called praxis. But even once praxis is understood as a necessary end of our learning, to grow past one’s “old self” is still a journey. With rich and vibrant imagery, Dee described that journey well, and for good reason; he would sail the world.

In Remaking a Life: Inside and Out, “Ms. V” underscored the relationship between writing and resilience, and demonstrated how resilience for her was a matter of both survival and dignity before her sentencing:

“So as each day passed I wrote in my journal & reminded myself that I needed to keep my sanity, and that I needed to stay motivated because even if I did get life, I didn’t want to lose myself; I wanted to be firm. I wanted to stand on my two feet and be strong enough to hear the results.”

Ms. V was firm, and remains strong as an integral part of the InsideOUT Writers staff today.

In Incarcerated Youth and Their Families: Human Just Like Everyone Else, Kathy G. noted how the health and well-being of a young person is a collective undertaking:

“When young people make mistakes, the consequences shouldn’t be so drastic. There needs to be more involvement in the communities to teach young people from an early age what is right and wrong so they can avoid places like jail.”

Kathy’s suggestion also touches on the very modern American problem that is a system which places so many people in environments where right and wrong means the difference between freedom or jail, as if there are no other ways to correct wrong.

From home to the world

In Make My President Black Again, Alton Pitre highlighted the importance for a young person to expand their horizons by traveling to learn from other cultures: “To really broaden their political knowledge, I would also advise that more young people travel around the world to meet other cultures. Last month, I was privileged to travel to Cuba for a week as a part of a study-abroad program through Morehouse. This was a very fun but humbling trip because I witnessed poverty at its finest in a Communist country long ignored by the U.S.”

Alton’s conversion from a seat in Central Juvenile Hall to a seat in the historic Morehouse College is a story in itself, but for Alton to visit Cuba with his college speaks to just how far so many “troubled” youth can and have got to go; we are all ambassadors in the making if given the opportunity.

If the American dream of opportunity is to fully be realized, however, Americans first have to know where we come from. Christine Alegre’s piece, How a Racist Jail System Changed Me, spoke precisely to this need:

“Black America has always been under attack, and what we see in the media today is the repercussions of a racism-forever mentality, as G.C. Wallace put it in 1963: “Segregation today, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever.” America never let go of its racist roots. Slavery built us, and prisons create an underclass of black and brown color. Black children are overwhelmingly seen as threats, and the names speak for themselves — from Emmett Till to Trayvon Martin and Tamir Rice.”

At the same time, the homes that are not homes to many system-impacted youth is another reality that our country has yet to come to terms with. In Left Behind, Danny Cervantes described the pivotal point of no return that too many system-impacted youth throughout America can relate with:

“The boy is 14 years old. I see a man is drunk and is starting to be violent. I see a confrontation between the boy and the woman’s husband. The boy is becoming a young man. He is standing up for himself for the first time in his life but is now coming out one of the rooms in the hallway. He has bags full of clothes and all of his personal belongings.”

Using a ‘bad hand’ for good

It is the challenge of a lifetime to work with youth whose support systems are denied them at ages as tender as 14 in their transition from adolescence to young adulthood. But there are also times when youth workers can only stand back and watch as young people take the world by storm.

In Art as Resilience, Taylor B. described how, after a lengthy episode with the state’s juvenile courts, she nevertheless pursued her education:

“I set my sights on graduating from school. I worked at earning credits while I was inside and in 2016 when I was released into placement, I kept at it. I was two years behind in my high school education, but this June I’m graduating with my high school diploma just in time.”

Taylor’s graduation was an amazing moment for all of IOW, but as an old saying goes: “After mountains there are more mountains.” She is now working as an executive production assistant for a local film company.

In Berkeley Bound, Rose M. tells readers of a critical moment in her coming of age: When she was recognized by a judge for successfully completing her placement program, the judge lavished her with praise:

“She told me to never forget who I was and to never give up on who I want to be. She was the reason my life changed for the better …”

But it was not easy. Rose’s attorney was terribly inadequate representing her throughout her placement. Rose was still moved by the experience to be better, however:

“... before I left the courtroom, I turned to the lead attorney in my case and thanked her, because if it wasn’t for her, I would’ve never have wanted to become a lawyer for at-risk youth.

“I told her that I would graduate from Berkeley Law School and become a lawyer for at-risk youth, and that I would make sure that my clients knew I would help them no matter what.”

With a similar sentiment, in Declaration of Inner-Presence, from South Central Los Angeles, David Velasquez elaborated on just how “a bad hand” in one’s environment can still be used to achieve self-fulfillment. He does this with the voice of a sage:

“In my own life, the consequences of the fast life in my youth didn’t create the end of my journey, but rather the beginning. I was given a second chance, time to think things through. I realized that, yes, certain people did give up on me before I had a chance. However, it wasn’t everyone who gave up on me. The same compassion that was given to me by those few on my side was what I had to give others in return.”

Words can save us

Alyssa R.’s essay builds on that very same sense of compassion. In The Department of Child and Family Services Mostly Failed Me, but Still I Persist, after a gripping account of her experiences through DCFS as a young woman, she still reaches out:

“... to the current foster youth out there: Your dreams are not dead. Never give up. We are all connected by our struggles and situations throughout systems like DCFS and beyond. You are not alone. Don’t let your past stop you; let it push you forward. Don’t be another statistic. We stand together, we are family.”

Her words are not to be taken lightly. In fact, if IOW’s writers make one thing clear, it’s that for youth everywhere in America, words can make all the difference in the world. Rachael G.’s poem for the series, Our Lives Are at Stake, described this with finality:

“... Poems are saving me

And poems are saving you.

Each stanza read,

And each written.

It’s hard sometimes

But best believe we will get stronger.”

I can only hope to continue to be as much support for these writers as they have been for me. Indeed, every one of them has saved me, but I know I’m not the only one who’s been saved by them. It’s been an amazing series. Thank you all.

Jimmy “Jimbo” Recinos, 27, is a writer from Central Los Angeles. When he’s not venturing through the city for his website JIMBO TIMES, he can be found at the InsideOUT Writers office, where he serves as an editor, instructor and community advocate for the program. He is a graduate of the University of California-Davis class of 2014 and an avid bookworm.