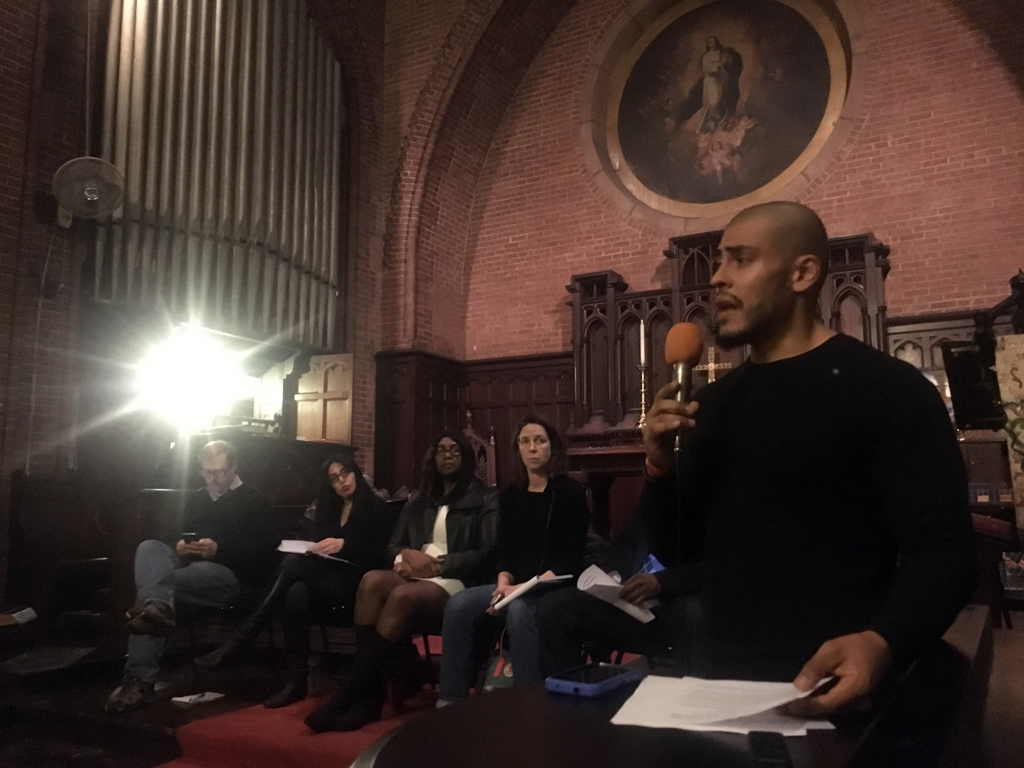

NEW YORK — Josmar Trujillo knows New York Police Department databases — facial recognition, DNA and, his crusade, the gang database. However, the database of juvenile fingerprints — illegally maintained and recently destroyed by the NYPD — was a new one for him. But, in the fight against big data policing, it was par for the course for Trujillo.

"I think that this latest revelation shows how the NYPD continually thumbs its nose at elected officials, lawmakers and laws, which is to say nothing of what they do to actual members of the public,” said Trujillo, a police reform activist and organizer.

The destruction of the database of juvenile fingerprints underscores concerns about accountability and transparency in the police department among activists and police reformers. They say this is not the first time the NYPD has overreached — and it will not be the last.

The destruction of the database of juvenile fingerprints underscores concerns about accountability and transparency in the police department among activists and police reformers. They say this is not the first time the NYPD has overreached — and it will not be the last.

“This is like a piece of a bigger puzzle that big data policing presents,” said Trujillo, one of the leaders in the fight against the NYPD’s controversial gang database. “We have to be very, I think, clear about what the battle is, and it has to be about getting rid of the NYPD's ability to track people in this way. Not just asking them to do it a little bit more fair. Not just asking them to be a little bit more transparent. But to actually take those abilities away to the extent that we can.”

The database, which was maintained for years, was in violation of the New York State Family Court Act. According to the Act, local law enforcement are not allowed to keep juveniles’ fingerprints. Instead, they are required to send them to the New York State Division of Criminal Justice Services (DCJS) and then immediately destroy them. Instead, the NYPD was storing them in their Automated Fingerprint Identification System database and saying they were sealed.

Christine Bella

“There are laws that pertain specifically to records that impact juveniles or young people because we don’t want them to face the same harsh collateral consequences that they would had they been arrested as adults,” said Christine Bella, a staff attorney with the juvenile rights practice at The Legal Aid Society. The Society is the New York City public defense provider that led the push for the destruction of the fingerprints.

“The fact that these records still exist would lend themselves to being available for future purposes,” she said. Sealing records does not offer the same protections to juveniles mandated by the Family Court Act as destroying does, she said.

‘More evidence’

The NYPD confirmed the destruction of the fingerprints in a statement last week. “The NYPD can confirm that the Department destroys juvenile delinquent fingerprints after the prints have been transmitted to DCJS,” said Detective Sophia Mason, an NYPD spokeswoman.

However, it would not say who destroyed them, when they were destroyed or how they were destroyed. An NYPD spokesman would not clarify whether the previously kept fingerprints was an official policy or an oversight by the department.

The Legal Aid Society first suspected that the NYPD were not destroying the records back in 2014 when a prosecutor admitted that their juvenile client was arrested based from retained fingerprints. After the case, they spent a year trying to confirm that their client’s fingerprints had been destroyed only to find out that they still existed and were instead sealed. This led them to suspect that their client wasn’t an outlier and that the NYPD was not complying with the Family Court Act by destroying juvenile fingerprints.

"It [the database] is yet more evidence of unlawful police surveillance tactics being used in New York City,” said Lisa Freeman, the director of special litigation and law reform in the juvenile rights practice at The Legal Aid Society.

With the database destroyed, Legal Aid is now calling on the New York City Council to pass the Public Oversight of Surveillance Technology Act, known as the POST Act, and to hold an oversight hearing. The legislation would require more reporting by the NYPD on surveillance technologies and how it uses them.

“We're reassured that they have issued policies now that give explicit instructions that call for destruction,” Freeman said. ”We also think that there needs to be close scrutiny by the City Council of police practices because this went on for decades and it was clearly unlawful.”

New York City Council Member Donovan Richards

Council Member Donovan Richards, the chair of the Committee on Public Safety, said he was concerned by the existence of the database but, sadly, not surprised. The database is consistent with the NYPD’s other concerning surveillance practices and another reason why there is need of accountability and oversight, he said.

“Our committee work has consistently aimed a light on the NYPD’s practices that skirt the line of infringing on privacy and we will continue to do everything in our power to push the department in the direction of reforms that better protect and serve the residents of New York City,” Richards said.

He anticipates hearings on NYPD surveillance in the coming months and said he looks forward to working with advocates and the police department on future oversight efforts.

Who polices the police

Past attempts at oversight have been slow moving. A bill that would require the NYPD to notify the families of juveniles who are in the gang database stalled earlier this year, and the POST Act has been in and out of the City Council’s agenda since 2017. A source who spoke on background so as to speak more freely who is familiar with how legislation moves through City Council said no one is stonewalling the attempts at oversight but that priorities shift with need. The source also said the council is relatively limited in what they can actually do to hold the NYPD accountable.

Taylonn Murphy Sr. is a social justice activist fighting against the use of the gang database. His son was in that database and was arrested in the 2014 West Harlem gang raid. He said he wants to know how he can trust that the NYPD actually destroyed the records without any independent oversight of the process.

“The unsettling part is who controls the oversight?” he asked. “Who is actually policing the department, you know?”

Like Trujillo, Murphy did not hear about the database until last week. He said that at first he was disturbed. But then he started to question it.

“I'm saying to myself, what for? What was the sense of keeping records of young people?” he said.

Murphy said he knew the importance of destroying records. He’d seen first hand that sealed juvenile records don’t stay sealed. During his son’s trial, the juvenile records for both his son, Taylonn “Bam Bam” Murphy Jr., and his murdered daughter, Tayshana “Chicken” Murphy, were unsealed.

“If they were able to open up Tayshana's sealed records and my son’s sealed records in a court proceeding, what made me think that they weren't still holding those things ... to utilize them when they saw fit?” he said.

For Trujillo, this is exactly the problem. In the era of big data policing, the NYPD has moved away from tracking crimes to tracking people. Fingerprints and files follow you and can be used against you, he said.

“They are trying to implement forms of surveillance that'll affect you at the earliest points in your lives and will follow you probably the length of your life,” he said, adding that they would have continued to keep the juvenile fingerprints had Legal Aid not caught them.

In keeping these files, the NYPD broke the law, he said. But the real issue is, when all is said and done, they won’t face any real repercussions for what they did. There is nothing and no one to hold them accountable and withhold resources from them as punishment. There is no law with “teeth,” he said, which means that a member of the NYPD can break the law for years without fearing much worse than a bad headline.

“At the end of it, the worst consequence for me [the NYPD] is that I finally have to comply,” he said.

Pingback: NYPD Fingerprint Database Just Part of ‘Big Data’ That Needs Oversight, Reformers Say – Bitfirm.co