As the pandemic raged, a Louisiana activist flashed back to the last time an outside menace threatened to invade detention facilities and kill those helplessly locked away.

Gina Womack

Gina Womack, executive director of Families and Friends of Louisiana's Incarcerated Children, had Katrina on her mind. In 2005 the Category 3 hurricane flooded Orleans Parish Prison and likely killed an untold number of detainees who were never evacuated from the New Orleans jail. Later 518 of them were unaccounted for, according to Human Rights Watch.

Fifteen years later, the novel coronavirus is spreading among those locked up — including juveniles — and the response in Louisiana recalls the silence that followed cries to release detainees before Katrina hit. Womack sent local elected officials a petition demanding the release of incarcerated children, When she got no response after a week, she was feeling deja vu.

“It seems like there's really no plan in place,” she said. “It seems as if Katrina never happened.”

While Katrina was visible on weather radar for four days before it hit land, COVID-19 has been on the country’s figurative radar all year. “A storm is coming,” as Vincent Schiraldi, co-director of the Columbia Justice Lab, recently put it.

While Katrina was visible on weather radar for four days before it hit land, COVID-19 has been on the country’s figurative radar all year. “A storm is coming,” as Vincent Schiraldi, co-director of the Columbia Justice Lab, recently put it.

Though the virus has hit juvenile facilities already, the worst is yet to come, say activists around the country. So they’re demanding the release of most of the 40,000-plus juveniles incarcerated in youth facilities. But only some locales seem to be listening.

Simple message, novel media

As state after state adopted social distancing rules, the traditional bullhorn and posterboard rally, which reliably attracted news coverage, was dead. The near-daily ritual in places like New York’s City Hall, where activists set up camp to chant, give speeches to cameras and persuade passing city council members to join their cause, was suddenly impossible. City Hall, where a coalition of activists declared victory on Oct. 17, 2019 when the council approved a plan to close Rikers Island, was now shut down entirely. Zoom conferences have filled the void.

Community-Oriented Correctional Health Services

Dr. Homer Venters

In a March 31 Zoom session that convened youth advocates from around the U.S., Womack and Dr. Homer Venters both highlighted the particular vulnerability of youth locked away. Incarcerated youth, they said, are disproportionately likely to have pre-existing health problems such as asthma that can make COVID-19 deadly.

The former head of New York City's correctional health services, now president of Community-Oriented Correctional Health Services, Venters said authorities would have trouble tracking the virus, as incarcerated youth might stay “outside direct vision” while they get sick in cells and dormitories.

“Release, release, release,” Venters said at the Zoom conference. “As a physician having managed outbreaks in places of detention, that's the number one objective.”

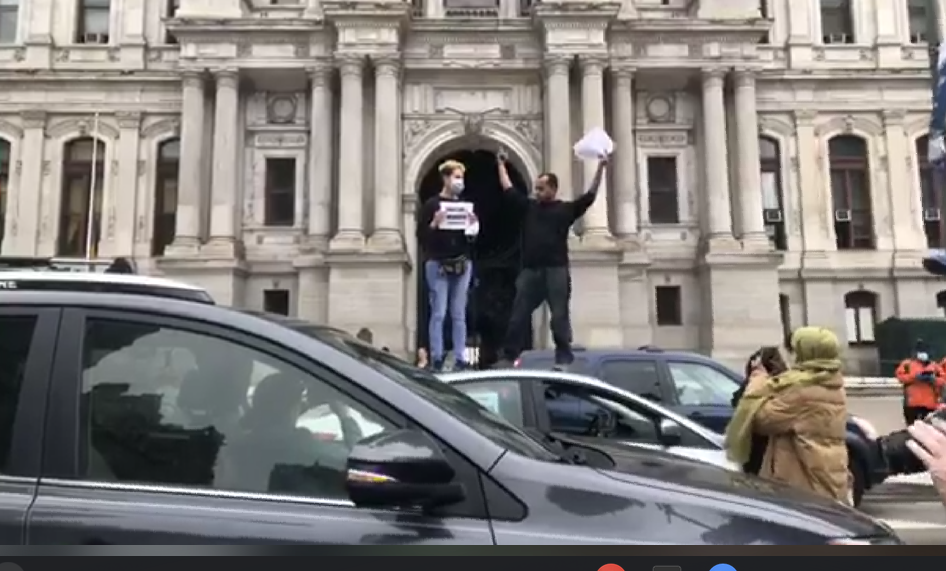

Using the hashtag #freeourpeople, Philadelphia activists had the same message as they filled three lanes of traffic with parked cars in front of City Hall on March 30, honking their horns and flashing signs from their windows. From atop a car, two activists demanded that Mayor Jim Kenney release those incarcerated pretrial and that the First Judicial District release those in jails and the juvenile detention center.

Philadelphia District Attorney Larry Krasner briefly stopped by, offering support, reported the Philadelphia Tribune. “I think it’s time for the governor to step up,” he said. “The mayor’s powers are more limited. ... use every tool in the toolbox so that we can all be safer as a people.”

Chesa Boudin

Another urban DA calling for the release of the incarcerated during the pandemic is San Francisco DA Chesa Boudin, who was also in the Zoom conference.

"The safety of the young people who remain in detention ... is an ongoing and daily concern,” Boudin said. Partially in response to coronavirus, his office has worked to halve the population of San Francisco’s Youth Guidance Center, where now only 15 to 17 youths are housed, he said. On Friday the number was down to 13.

His elderly father is imprisoned in New York’s Shawangunk Correctional Facility on a 75-year sentence stemming from a deadly armed robbery. “I worry every day about my father’s health in a facility … that doesn’t have a single doctor on staff,” he said.

Emergency legal actions

On Wednesday, two days after the car protest, the Juvenile Law Center in Philadelphia asked the Pennsylvania Supreme Court to release all juveniles held by the state who are medically vulnerable or don’t pose a threat, including those facing adult charges, reported the Philadelphia Inquirer.

Joined by the Youth Sentencing & Reentry Project and law firm DLA Piper, the Juvenile Law Center filed a King’s Bench petition, an emergency action that allowed them to address the state’s highest court directly.

“We cannot allow our vulnerable youth to be left behind in physical settings that actually promote, rather than impede or stop, exposure and contagion,” said Marsha Levick, chief legal officer of Juvenile Law Center, in a statement.

Decarcerate PA

Decarcerate PA demanded that some prisoners be freed to avoid getting the COVID-19 virus.

In New York City, the Legal Aid Society sued the city’s Administration for Children’s Services, which is responsible for the youth who are held in secure and nonsecure facilities within the five boroughs. They estimated there were 22 in juvenile detention.

As of today four teenagers held in city juvenile detention facilities had contracted the coronavirus, as had 10 staffers. The youth were said to be "recovering well."

Advocates fear every facility will turn into Rikers Island, where most adults in the city are held pretrial or on parole violations. As of Sunday, the city’s jails had 273 confirmed COVID-19 cases out of a population that the Legal Aid Society said was 4,422 on Friday. That makes for an infection rate of 6%. City corrections department staff accounted for an additional 321 cases, and 53 correctional health staffers of the city’s Health + Hospitals department have tested positive for the virus.

The pandemic didn’t affect New York state legislators’ efforts to roll back bail reforms that had been in place only three months, potentially expanding the population of the city’s jails. On Thursday the Democrat-dominated state legislature passed a budget that expanded the state’s roster of bail-eligible offenses. It passed with just a handful of Senate progressives — and almost two dozen in the Assembly — voting “no.”

Some states make moves

On March 29 Gretchen Witmer, governor of hard-hit Michigan, ordered that juveniles in detention and residential placement be released “unless a determination is made that a juvenile is a substantial and immediate safety risk to others.” That followed a March 19 call from the Michigan Center for Youth Justice.

On Friday, Michigan’s Kent County announced three COVID-19 cases among youth and two staff cases at its Juvenile Detention Center in Grand Rapids.

In Clayton County, Ga., which includes the suburbs south of Atlanta, Steven Teske, chief judge of the juvenile court, said he’s doing anything he can to get juveniles out of custody. Since 2002, he said, the average daily population of the county’s youth detention center has plummeted from 62 to about 15. Since mid-March, he has conducted disposition hearings over Zoom, aiming to divert enough kids to cut that lower number by half — or even more.

And that, he says, will likely become the new normal for the county.

“I told my staff, get ready, because we're probably going to change our policy,” Teske said. “That what we have done, thinking it would only be temporary, would become permanent. That's what this pandemic has forced me to do, is to look at this issue much differently, much deeper, more critically. Here I am, 60 years old, and I'm still learning that there's always more you can do.”

This story has been updated.

Washington State (and several other states) only require an internet check in using a thumb print at a Kiosks now for parole and probationers. Now when prisoners are being released as “low-level” offenders (who need not have been imprisoned in the first place considering the cost etc)

I think in the budget crunch that follows the COVID-19 we should all press for the use of Kiosks as an already viable alternative as we press for lowering the prison and jail populations and particularly for juveniles because to return to funding the old prison/ jail models that cost way too much even when there was no COVID-19 recession.